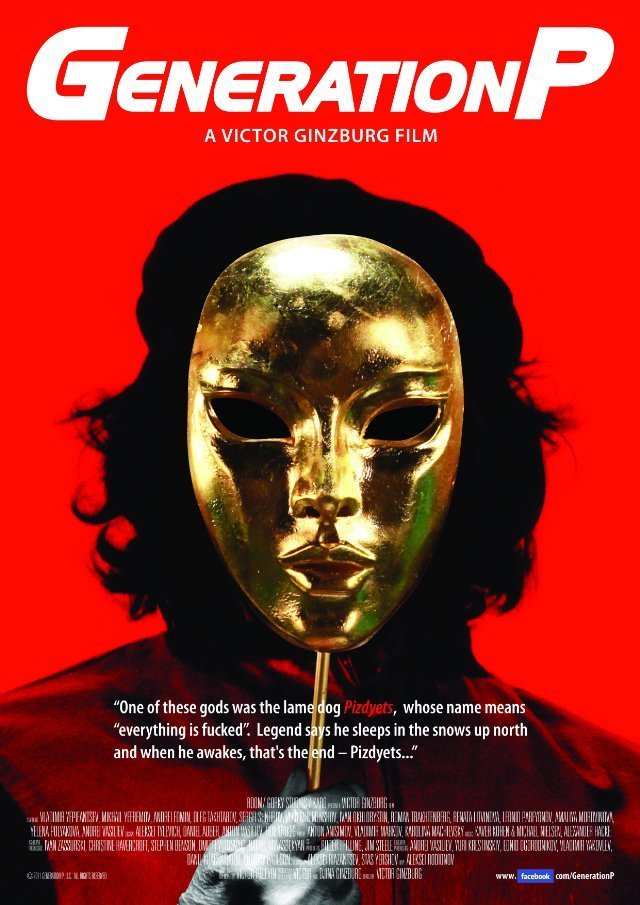

“Generation P” appears to be Russian slang for Generation Perestroika and “The Pepsi Generation,” which nicely reflects this film’s cockamamie spirit, sort of a cross between “Mad Men” and an acid trip. Set in the years immediately after the fall of communism, “Generation P” would have been unthinkable any earlier, and now is merely incomprehensible. It is said to be a huge success in Russia — a daring, transgressive satire. Non-Russians, however, may need a program to understand the players.

The film’s hero is Babylen Tatarsky (Vladimir Epifantsev), jobless and homeless at the outset, then reduced to manning a shabby kiosk where he sells cigarettes one at a time. Through an old mutual friend, he’s lured into Russia’s advertising industry (“It’s a Gold Rush! But in a few more years, it’ll all be snatched!”).

These establishing scenes are the movie’s most entertaining. Babylen free-associates with his new colleagues about Coke and Sprite, Marlboros and Parliaments. His nifty new tag line for Sprite (the UnCola) is shot down because it already belongs to 7-Up. His inspiration for Parliaments (put the Russian Parliament on the package) gets a little further. Untold sums of money begin to roll in. Babylen undergoes a fashion makeover and cuts his scraggly hippie hair.

All fun. And if director Victor Ginzburg had kept pushing in that direction, the film might have been more successful. Maybe he was simply following the source novel by Victor Pelevin, unread by me. The movie begins to come apart when Babylen overdoses on LSD (“enough for a battalion”) and the movie goes berserk in acidland. The hero’s name is inspired by Babel and its fateful tower, and indeed, he begins speaking in words no one can understand. Inside a weird structure resembling the Tower of Babel, he encounters the priests of a cult and seems to go tiresomely astray.

I learn from Variety that director Victor Ginzburg was a Russian expatriate working in Venice, Calif. The movie, by Russians and for Russians, contains interesting notions of their view of the U.S. Our consumer goods are fascinating to them. Babylen and a colleague discuss why America “hates” them. It’s because they buy American cars, cigarettes and clothes, and then Russians get back American money. By that token, China hates the United States, too.

A lot of the film’s material involves the use of CGI to create fake Russian political figures and even run them for office. No doubt that stuff will reverberate comically in Russia, but American viewers may feel a little lost.