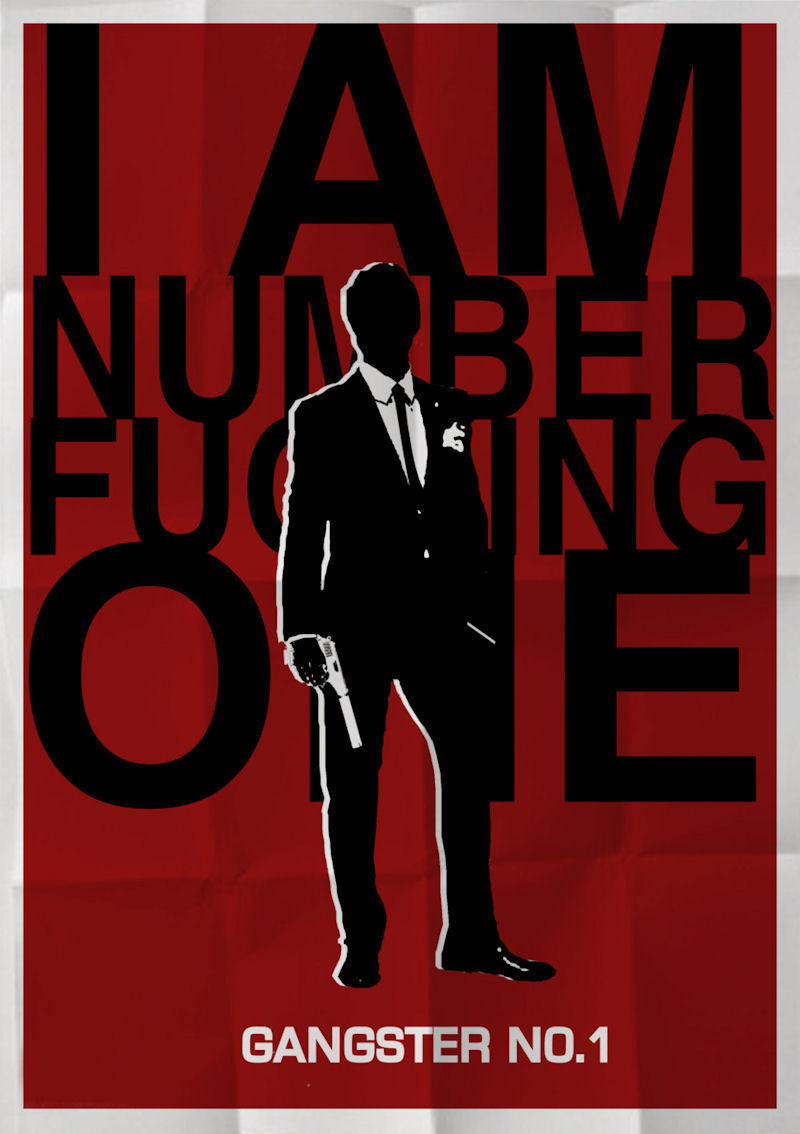

If Alex DeLarge of “A Clockwork Orange” had become a London gangster, he might have turned out like the hero of “Gangster No. 1.” The movie encourages that connection by casting Malcolm McDowell, the original Alex, as the character grown old. Paul Bettany, who plays Young Gangster, is often photographed with his eyes glaring up from beneath lowered brows, which was the signature look Stanley Kubrick gave Alex. Another connection: The movie contains a beating of startling brutality, scored by a pop song played at top volume. The movie is inspired, as all modern London gangster movies are inspired, by the notorious Kray brothers. It isn’t based on their lives or deeds, but on the aura of evil they so successfully projected; they often got their way without violence, because they seemed so capable of it. In “Gangster No. 1,” the crime family is led by Freddie Mays (David Thewlis), who in 1968 is a young, sleek, expensively groomed hood who runs a nightclub and surrounds himself with hard men; he’s known as the Butcher of Mayfair. One day he summons Young Gangster, tosses him a roll of bills, hires him and seals his own fate.

The movie, directed by Paul McGuigan, begins in 1999, with Young Gangster grown middle-aged and cold-eyed. McDowell plays the character as a man who has lost all joy, retaining only venom.

We see him with cronies at a private boxing club; they’re laughing uglies, drinking champagne, smoking cigars, recalling the violent days of their youth (significantly, their memories are starting to be unreliable). Then he learns that Freddie is getting out of prison, his eyes narrow, and we go into the flashback.

The 1968 events have been called Shakespearean, which is fair enough, since just about everything is Shakespearean. They also have a touch of Freud. Young Gangster admires Freddie enormously, wants to be like him, and is probably half in love with him. When Freddie falls in love with the nightclub singer Karen (Saffron Burrows), Young Gangster is consumed with jealousy. In one of the movie’s strongest scenes, he confronts Karen, who not too subtly offers to help him find a girl, and then spits in his face.

Bettany’s reaction shot is a piece of work. His face screws into a rictus of hate, he seems about to hit her, and then, by an act of will, he starts smiling–which is even more frightening. There has been a gangland feud between Freddie and a rival named Lennie Taylor (Jamie Foreman), and when Young Gangster learns of a planned hit on Freddie and Karen, he goes to the location, stays in his car, and watches it like a drama. Then he kills Lennie, to frame Freddie for the murder.

The sequence involving this murder is one of the most brutal and, it must be said, successfully filmed acts of violence I have seen. Chilling, how Young Gangster breaks down the door of Lennie’s flat, shoots him in the knee, then carefully takes off his coat, shirt, tie and pants, because he doesn’t want them bloodied in the events ahead. Then he unpacks a tool kit, including a hatchet, a hammer and a chisel. The attack is seen through Lennie’s point of view, as he fades in and out of consciousness. Another piece of work.

The movie is exact in its characters and staging, using Freddie’s sunken living room conversation pit as a kind of stage; the man in power towers over the others. But I am not sure the ending really concludes anything. We see Freddie and Young (now Old) Gangster in a final exchange of information, revelation and emotional brinksmanship, but then there’s a coda with the older gangster on a rooftop, shouting for all the world like the bitter loser in a 1930s Warner Bros. crime movie. This conclusion is too pat to be satisfying, but the film has a kind of hard, cold effect.