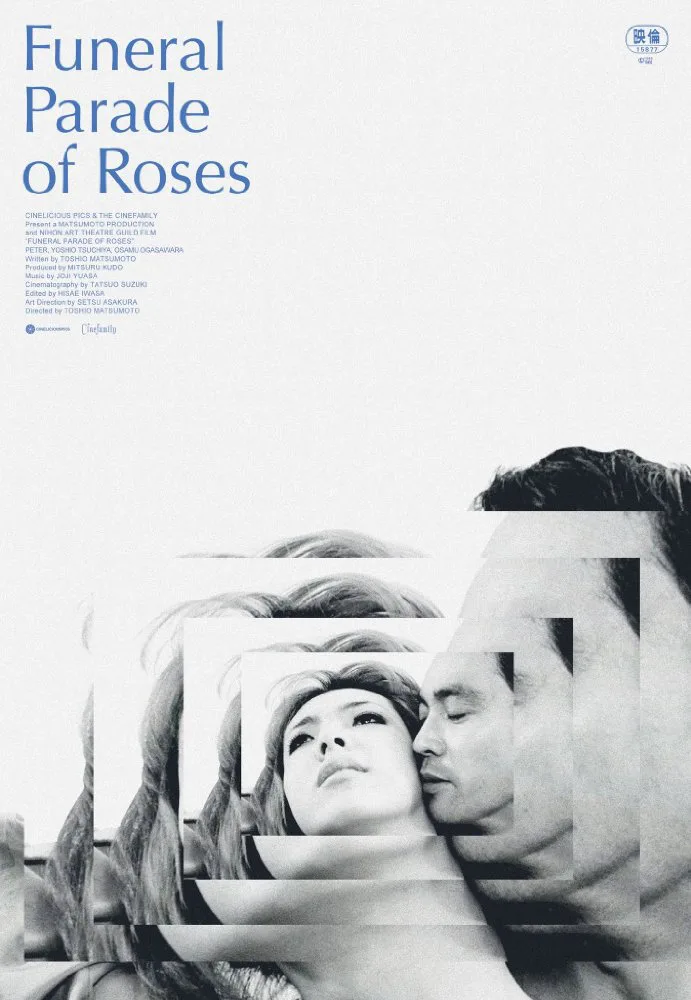

Avant garde queer/proto-punk drama “Funeral Parade of Roses” is simultaneously a product of, and very much ahead of its time. Like many other filmmakers that produced radical, challenging work during the Japanese New Wave of the ’60s and ’70s, “Funeral” director/writer Toshio Matsumoto was influenced by the films of the French New Wave, especially the work of Jean-Luc Godard. “Funeral Parade of Roses” would go on to be an acknowledged influence on Stanley Kubrick, specifically a major inspiration for Kubrick’s “A Clockwork Orange” adaptation. But Matsumoto’s film is closer in style to Godard’s films than Kubrick’s since Matsumoto was, like the director of “Breathless” and “Contempt,” trying to make a new kind of film.

“Funeral Parade of Roses” does have a traditional narrative: transvestite Eddie (Pita) struggles with his identity while he and his lover Jimi (Yoshiji Jo) try to avoid detection from Jimi’s main squeeze Leda (Osamu Ogasawara). But, in order to interrogate the way Japanese mainstream and counter-culture both fetishize and alienate members of the gay and transgender community, Matsumoto frustrates viewers’ attempts at understanding Eddie based solely on his actions. We are treated to jarring flashbacks to Eddie’s past, which hint at childhood molestation and a bloody murder. And we’re treated to interviews with Japanese “gay boys,” or drag queens who confess that they do not know why they choose to dress up like women.

And every so often, music cues—specifically organ versions of schoolyard jingle “The More We Get Together” and Jacques Offenbach’s “Infernal Gallop”—are sped up, chopped-up, or slowed-down to remind us that we’re watching a movie. Matsumoto also periodically interrupts whatever action is happening on-screen by yelling “Cut” and revealing his crew working behind the camera on any given scene. Several scenes are interrupted with abstract word salad, like “Roses!” and “Sun, Severed Head.”

But what does “Funeral Parade of Roses” mean? Many times the film interrogates its value as a work of counter-cultural discourse. It presents an ambivalent love/hate attitude towards sex and cinematic language that suggests that Matsumoto wasn’t sure if he could make a meaningful statement on Eddie’s identity as a sexually active cross-dresser. He unravels layers of his characters’ performative identities, and pokes fun at Eddie’s colleagues’ pretentiousness. Some of them, like pontificating stoner beardo Guevara (Toyosaburo Uchiyama), solemnly quote their favorite artists. Others are satisfied with the hypnotizing effect of the movies that they make, and pat each other on the back while seeking each other’s approval: “What do you think?”

But sex, like moviemaking and melodrama, is not an either/or proposition in “Funeral Parade of Roses.” Eddie is performing for his clique, and he enjoys the attention that he receives from men like Jimi and his clients. But he also feels the futility of trying to rebel using his body/sex as a means of self-expression. Eddie willingly chooses to get stoned and stripped by peers in one drugged-out, quasi-Utopian scene. But that sequence is tonally just a stone’s throw away from the film’s many sex scenes, which bring to mind the way Alain Resnais filmed sex in “Hiroshima, Mon Amour” as a tangle of questing, insatiable disembodied limbs. You hear Eddie’s ragged gasps. And you see him trying to find succor in art, whether it’s a bank of posters for Pasolini’s “Oedipus Rex,” or a die-in performed by student activists. But no matter where Eddie goes, he is implicitly confronted by the limitations of speech, of language, and of his self.

Maybe there’s no way to express yourself. Maybe we can only communicate and/or define ourselves through limited means, and the people who consider themselves most free are ultimately trapped by other people’s preconceptions. Maybe there’s no hope beyond the temporary relief we find in each other’s arms. Matsumoto doesn’t definitively or authoritatively speculate on the nature of human existence beyond trying to capture as much of its humorous ironies, and heart-ache-inducing ironies.

Instead, Matsumoto experiments with what he can say by juxtaposing images through jarringly edited montages, and artificially manipulated song cues. Godard may be his spiritual predecessor, but “Funeral Parade of Roses” is a heady, emotionally resonant work of art that stands apart from Matsumoto’s influences, and even his influencees. All praise due to Cinelicious for digitally restoring and re-releasing such a vital, ineffably strange film. You may not directly identify with Eddie or his world, but you will walk away from Matsumoto’s film with a newfound appreciation of what movies can be.