Why did Chevy Chase want to play I.M. Fletcher, the laconic hero of Gregory McDonald’s, bestsellers? Was it because Chase saw a way to bring Fletch to life? Or was it, more likely, because Chase thought Fletch was very much like himself? The problem with “Fletch” is that the central performance is an anthology of Chevy Chase mannerisms in search of a character. Other elements in the movie are pretty good: the supporting characters, the ingenious plot, the unexpected locations. But whenever the move threatens to work, there’s Chevy Chase with his monotone, deadpan cynicism, distancing himself from the material.

“Fletch” is not the first movie that Chase has undercut with his mannerisms, but it is the best one-since “Foul Play,” anyway. His problem as an actor is that he perfected a personal style on “Saturday Night Live” all those many years ago, and has never been able to work outside of it. The basic Chevy Chase personality functions well at the length of a TV sketch, when there’s no time to create a new character, but in a movie it grows deadening. “Fletch” is filled with a series of extraordinary situation, and Chase seems to react to all of them with the same wry dubiousness.

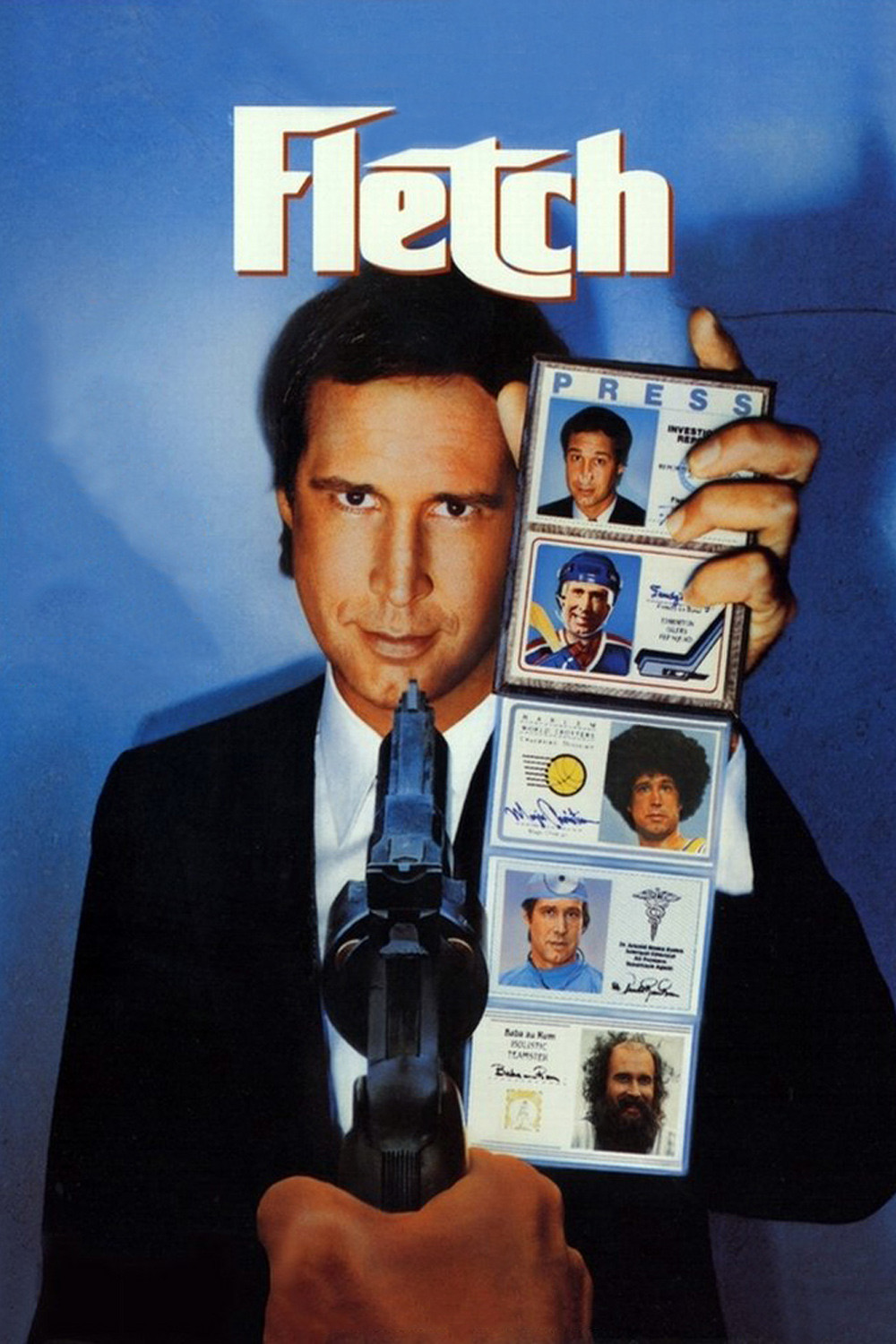

His character this time is an investigative reporter for a Los Angeles newspaper. Deep into an investigation of drug traffic on the city’s beaches, Fletch is approached by a young man (Tim Matheson) with a simple proposition: He wants to be killed. The story is that Matheson is dying of cancer and wants to die violently so his family can qualify for enlarged insurance benefits but Fletch doesn’t buy it. Something’s fishy and Fletch pretends to take the job while conducting his own investigation.

The case leads him to an extraordinary series of interesting characters; the film’s director, Michael Ritchie, is good at sketching human original, and we meet an aging farm couple in Utah, a manic editor, a no nonsense police chief, a mysterious drug dealer, a slimy doctor, a beautiful wife and a lot of mean dogs.

Every one of the characters is played well, with the little details that Ritchie loves: The scene on a farmhouse porch in Utah is filled with such sly, quiet social satire that it could stand by itself. The movie’s physical comedy is good, too. A scene where Fletch breaks into a Realtor’s office – scaling a fence and outsmarting vicious attack dogs – is constructed so carefully out of comedy and violence that it’s a little masterpiece of editing.

The problem is, Chase’s performance tends to reduce all the scenes to the same level, at least as far as he is concerned. He projects such an inflexible mask of cool detachment, of ironic running commentary, that we’re prevented from identifying with him. If he thinks this is all just a little too silly for words, what are we to think? If we’re more involved in the action than he is, does that make us chumps? “Fletch” needed an actor more interested in playing the character than in playing himself.