In the opening scenes of Jeff Maloof and Charlie Siskel’s “Finding Vivian Maier,” its titular subject is described as “paradoxical”, “bold”, “eccentric”, and other words that get at the fact that the men and women who were closest to Maier in her time on Earth didn’t really know much about her. In 2007, Maloof was working on a book about his Chicago neighborhood and longed for the right archival photography. A flea market junkie from a young age, he took a risk at an auction, bidding on a box of negatives that he never ended up using and shoved in a closet. Two years later, he developed them out of curiosity and discovered a woman now considered one of the best photographers of the 20th century. When the best of Maier’s work first appears in the film about her, the quality takes your breath away and sends chills down your spine. She was a true talent. And yet Maloof and Siskel’s film presents an interesting moral quandary along with its profile of an amazing photographer. When does creative ability and the desire to share a true artist’s eye trump what has to be considered an invasion of privacy?

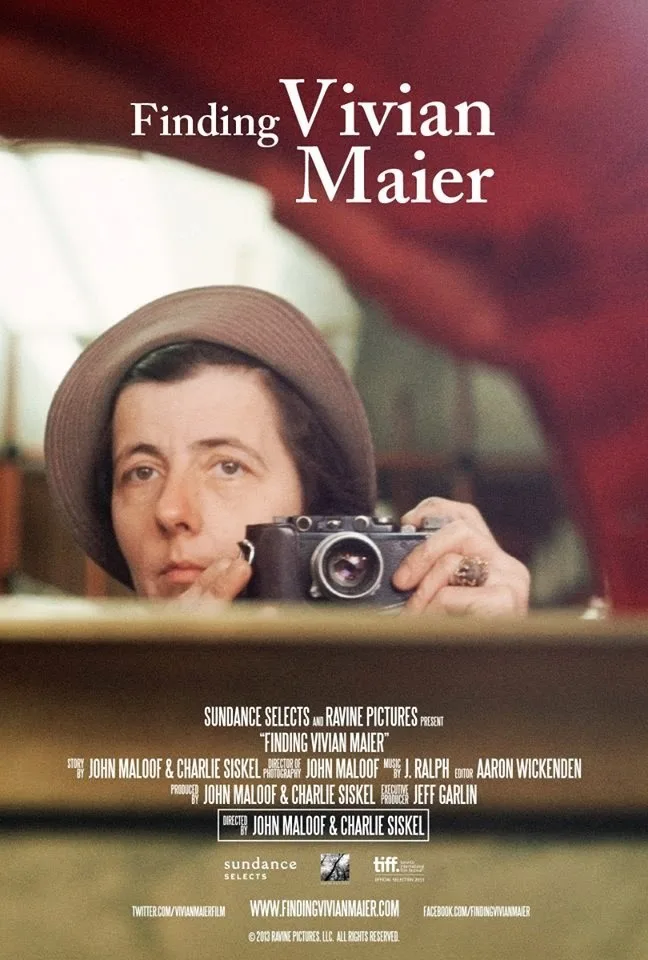

The story of “Finding Vivian Maier” progresses from Maloof’s auction find to his scanning the developed photos into a Flickr account and realizing that he wasn’t alone in his assessment of Maier’s talent. And so he went after the rest of the story, trying not only to find the rest of the negatives but Maier’s back story, and how it impacted her photography. Immediately, significant questions haunted Maloof. Why did she never show her work to anyone? Why did she shoot over 150,000 photos, most of them from a box camera that she always carried around her neck and could surreptitiously use to capture her subjects? And what’s the point of taking so many photos if no one sees them?

When Maloof discovers that Maier recently passed and is allowed access to her storage unit, a portrait of a hoarder becomes more clearly defined. She didn’t just take 150,000 photos. She kept receipts for decades, collected trinkets, stacked newspapers to the point that her floor sagged. She rather quickly goes from “eccentric” to mentally ill, especially when stories of her relative disregard for many of the children she nannied come into focus. (One family speaks about the photos she took when one of her wards was hit by a car and the behavior turns to honest mental and physical abuse later in life). She often gave fake names and some claim she used a fake accent. She wanted to be hidden, private, and reclusive. Just because she once looked into selling photos doesn’t change the mountain of behavior that suggests that she saw her negatives and photos as something else to fill the storage unit of memories.

And now all of that is being torn down. The argument has been made that Maier’s photos are fair game because she didn’t destroy the negatives. She didn’t destroy ANYTHING. She kept receipts buried in trinkets in envelopes in boxes. And the film raises the question of privacy regularly with people who knew Maier commenting on how much she would have loathed this investigation into her life and Maloof wondering aloud if he’s gone too far. Sadly, the filmmakers brush it off by answering the question with their fascination with this odd, talented outsider artist. Curiosity is used an excuse to invade privacy. Not good enough. If they had taken a strong stance and simply stated that art is meant to be shared and displayed no matter the artist’s wishes, I might have actually agreed. But the invasive nature of “Finding Vivian Maier” is only briefly given lip service and never adequately handled (within the film…the creators supposedly have dealt with the issue elsewhere but this is a review of what’s in the film itself and not supplemental material).

Is it possible to love the art but disagree with the way it’s presented? Vivian Maier’s photography is absolutely incredible and now that it’s been unearthed and her past has been investigated, her talent should be appreciated. And so I’m incredibly torn about “Finding Vivian Maier” overall. Should Maloof and Siskel have opened a door that a dead woman so clearly wanted locked? I’d say no (or they should have done so with more authority and artistic justification instead of just glossing over the issue with “But isn’t she interesting?”). And yet now that it’s open, it can’t be closed again. Perhaps when Maloof posted those photos on Flickr, there was no turning back. And oh is it ever fascinating what is behind that door.