Young love is idealized as sweet romance, but early sexual experiences are often painful and clumsy and based on lies. It is not merely that a boy will tell a girl almost anything to get her into bed, but that a girl will pretend to believe almost anything, because she is curious, too. “Fat Girl” is the brutally truthful story of the first sexual experiences of a 15-year-old sexpot and her pudgy 12-year-old sister.

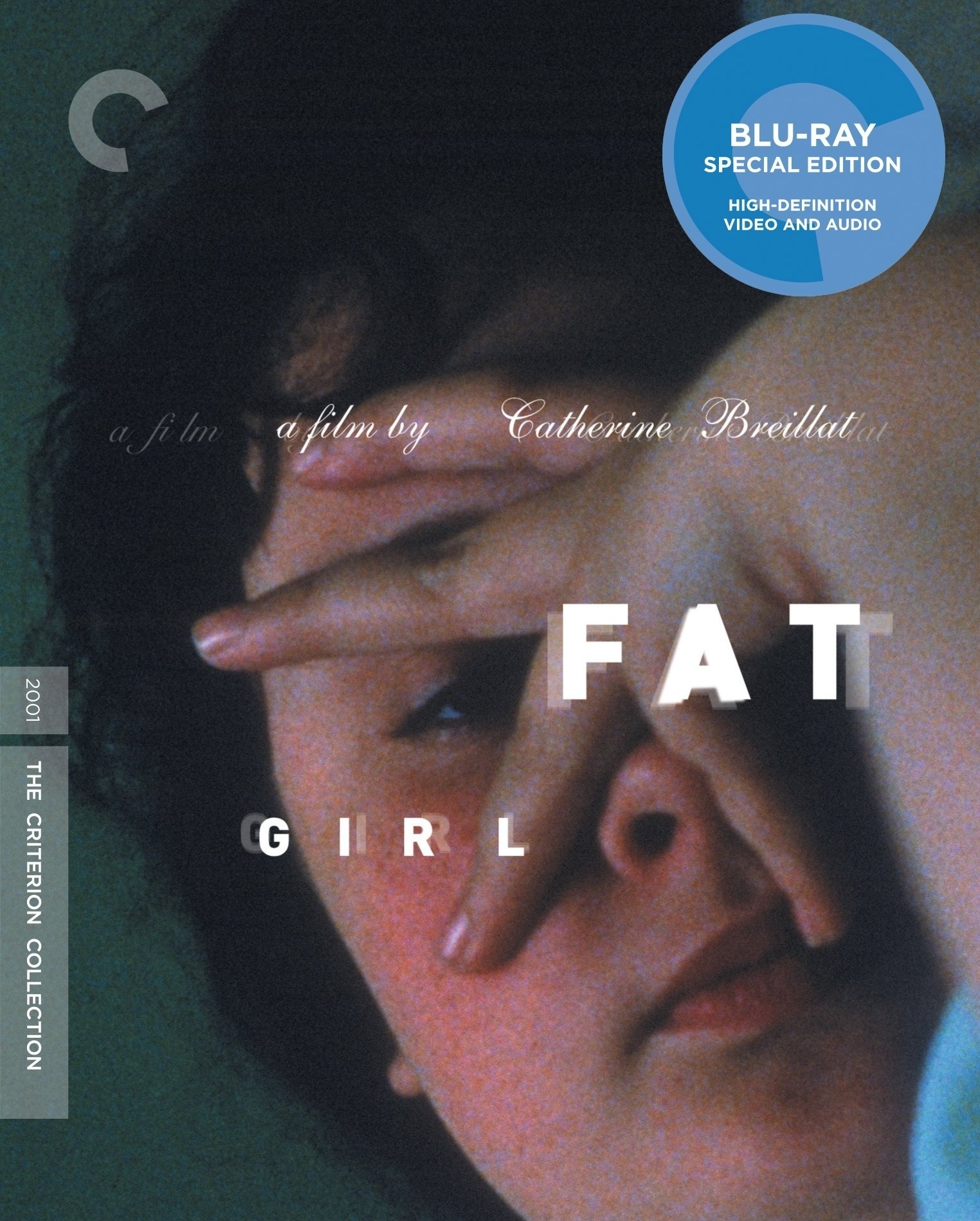

The movie was written and directed by Catherine Breillat, a French woman who is fascinated by the physical and psychological details of sex.

Her characters may talk of love, but they rarely feel it and are not necessarily looking for it: Her women, as well as men, have a frank curiosity about what they can do–and what can be done–with their bodies.

Her previous film, the notorious “Romance” was about a sexually unsatisfied woman who goes on a deliberate quest for better sex–and if that sounds like a porn film, “Romance” is not about ecstasy but about plumbing, sweating, hurting, lying and loathing.

“Fat Girl,” seemingly more innocent, at times almost like one of those sophisticated French movies about an early summer of love, turns out to be more painful and shocking than we anticipate. It is like life, which has a way of interrupting our plans with its tragic priorities. True, Anais (Anais Reboux) achieves a personal milestone, but at what cost? The movie takes place in a summer resort area. Anais and her sexy 15-year-old sister, Elena (Roxane Mesquida), are vacationing with their mother (Arsinee Khanjian). Their father (Romain Goupil) is a workaholic for whom the family is just one more item on his to-do list. Elena attracts the attention of the local boys, and her overweight kid sister looks on with smoldering jealousy: Anais at 12 is smarter and in certain ways more grown-up. She is eager for a sexual experience, although she has little idea what that would entail (in one sad-sweet scene in a swimming pool, she imagines a romantic rivalry for her affections between–a pier and a ladder). In another scene, she eats a banana split in the back seat while watching Elena necking in the front.

Fernando (Libero De Rienzo) comes sniffing around. He is older, a law student, also on vacation. Elena finds his attention flattering. He speaks of love, is vague about the future, insistent about his demands.

What Breillat sees clearly is that Elena is not an innocent who is deceived by his lies, but a curious girl with high spirits who wants to believe. Yes, she says she wants to keep her virginity (Anais wants to lose hers).

But virginity and purity for Elena are two very different things. Like a lover in a Latin farce, Fernando climbs in through the bedroom window one night, and the “sleeping” Anais watches as Elena and Fernando have sex. What do they do? There is, no doubt, a French phrase for the words “everything but.” Breillat has no false sentimentality about women, no feeling that men are pigs. Sentiment and piggishness are pretty equally distributed between the sexes in her movies.

Consider a sequence in which Fernando steals one of his mother’s rings and gives it to Elena, not quite saying what he promises by it. And then how Fernando’s mother calls on Elena’s mother to get the ring back. We discover that the ring is part of a little collection Fernando’s mother has of jewelry given to her by lying men; if she had a sense of humor, she would see the irony in how it has been passed on.

The private scenes between Anais and Elena are closely observed. The girls say hateful and insulting things to each other, as young adolescents are likely to do, but they also share trust and affection, and talk with absolute frankness about what concerns them. Elena’s dalliance with Fernando ends unhappily, but then of course in a way she knew it would.

Anais is left raging with jealousy that she is still a virgin, and she is at least more realistic about life than Elena; when she loses her virginity, she says, it will be without love, to a man she hardly knows, because she just wants to get it out of the way and move on.

The film has a shocking ending, which Breillat builds to with shots that are photographed and edited to create a sense of menace. This ending leaves the audience stunned, and some will be angered by it. But consider how it works in step with what went before, and with the drift of Breillat’s work.

This is not a film softened and made innocuous by timid studio executives after “test screenings.” There is a jolting surprise in discovering that this film has free will, and can end as it wants, and that its director can make her point, however brutally. And perhaps only with this ending could Anais’ cold, hard, sad logic be so unforgivingly demonstrated.