Back in 2016, director Paul Feig and co-writer Katie Dippold tried to further include women aside from Sigourney Weaver and Annie Potts in the Ghostbusters universe, and the experiment was met, from the worst corners of the fanboy universe, with a thorough rejection. The Twitter response was vitriolic. The film underperformed at the box office. And the upcoming “Ghostbusters: Afterlife” pivots away from the female foursome introduced in the 2016 film, instead focusing specifically on the original, all-male team. The message couldn’t be clearer from a certain type of paranormal-comedy fan: No women allowed.

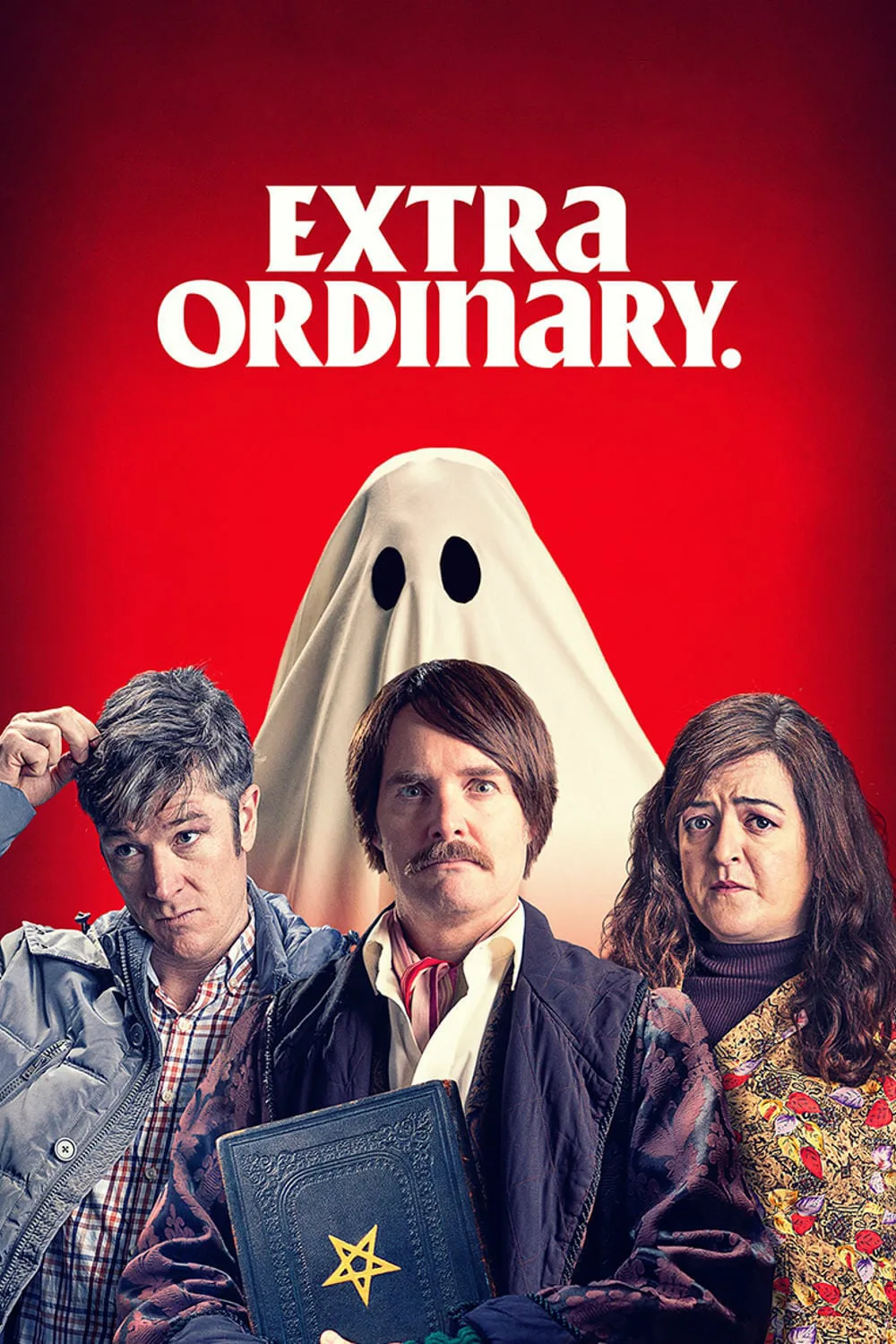

The narrow-mindedness of that refusal is part of why “Extra Ordinary,” from Irish filmmaking duo Enda Loughman and Mike Ahern, feels so satisfying. There is a warmth to this film, an easy charm, that comes from a script aware of the genre conventions with which it’s experimenting and from a cast willing to jump headfirst into whatever surrealism is required. There are explicit references to the Ghostbusters without an accompanying narrative debt to the franchise; “Extra Ordinary” gets goofier and bloodier than Venkman, Ray, Egon, and Winston ever did. Instead, much of the humor here is in line with the British Three Flavours Cornetto trilogy by Edgar Wright, and the idea that the smallest towns are the strangest, banal situations the weirdest, and “normal” people the ones most likely to be secret Satanists.

That duality is what Rose Dooley (Maeve Higgins) has been aware of her whole life. Rose is the daughter of paranormal expert Vincent Dooley (Risteárd Cooper), who was locally famous in Ireland for his videotape series “The Talents,” in which he investigated various supernatural occurrences, and she is trying to leave that part of her life behind. She can see ghosts, sure, but for the most part, they’re quite mundane. A toaster’s electrical cord, floating in midair. An askew branch in a roadside tree, waving at her. Rose knows they’re there, and other people know that Rose knows they’re there, but Rose just wants to run her driving school during the day and go home to a dinner of frozen lasagna each night. Her talent is real, but she’s afraid to use it after a tragic experience years before.

Meanwhile, on the other side of town, in a gigantic castle decorated with various occult paraphernalia, lives one-hit-wonder Christian Winter (Will Forte, delightfully maniacal). Years after his song “Cosmic Woman” made him an international star, Christian is still looking for his next success (sadly, the album I Like My Hat just didn’t find an audience). Desperate to be rich and famous once more, Christian makes, literally, a deal with the devil: a virgin sacrifice for one more chance at wealth and celebrity.

Christian’s targeting of 16-year-old Sarah Martin (Emma Coleman), and a plea from Sarah’s father (Barry Ward) to Rose for help, shifts the comedy into race-against-time mode. The key here is Higgins as Rose, whose grasp of her character’s quirkiness is perfect: an experienced kicking off of her pants as soon as she gets home from work; how exuberantly she waves to an elderly woman on the side of the road, mistakenly believing the stranger is a ghost; the bashfulness with which she admits to Martin that she’s developed a bit of a crush on him. Higgins is boundlessly lovable, and she effectively communicates Rose’s conflicted feelings about using her talent while also making clear how her affection for the Martin family inspires her.

The rest of the ensemble is equally excellent, particularly Ward, who demonstrates an improv-like flexibility later in the film when Martin’s body is repeatedly inhabited by various spirits trying to communicate with Rose, and Forte, who is reliably wacky as a Satanist looking for just a little respect from his impatient wife, Claudia (Claudia O'Doherty). Their antagonistic dynamic, with Christian trying to follow the rules of his occult ritual by the letter and Claudia’s sole obsession being a scheme to get free Chinese food delivery, helps sell the absurdity at the heart of the film.

Performances aside, not everything in the movie’s final act works as well. “Extra Ordinary” uses Vincent Dooley’s Talents episodes as a framing device for the first two-thirds of the film, with questions like “Do Ghosts Have Feelings? and “What is Evil?” Those queries operate as a guide for the plot and break supernatural elements into easily digestible bites of content, but without that framework for the ending, the movie’s conclusion doesn’t feel as tightly focused. As a result, the punchy script relies a little too often on vulgar humor to round out its jokes, and a gag about the minute details of a character’s virginity seems to come out of nowhere.

But when “Extra Ordinary” finds the right wavelength for its wackiness, the script and the cast effectively straddle the line between gross-out gore and silly small-town melodrama. The explosion of blood captured in a Talents video about goat sacrifice is the former, and Forte’s Christian irritatedly complaining to his wife that he misspelled Beelzebub because of her nagging is the latter. And what consistently lands is the movie’s low-key but persistent argument that there is a place for women in this world of ectoplasm and possession, and that their expertise is just as valid—and just as impactful—as the work of any man. The Ghostbusters franchise may have stepped back from that idea, but the cheery, whole-hearted embrace of it is key to the appealing enthusiasm of “Extra Ordinary.”