Orson Welles once described his approach in “Citizen Kane” as “prismatic,” and while there are many differences in subject and style between that cinema milestone and Michael Almereyda’s “Experimenter,” the two films share a multi-faceted formal playfulness and an essential intellectual seriousness that make them similarly bracing, original and thought-provoking. Part of the latter quality comes from their focus on men (one semi-fictional, the other real) who stand at particular junctures of American history and, like prisms, refract converging elements of our national identity and culture.

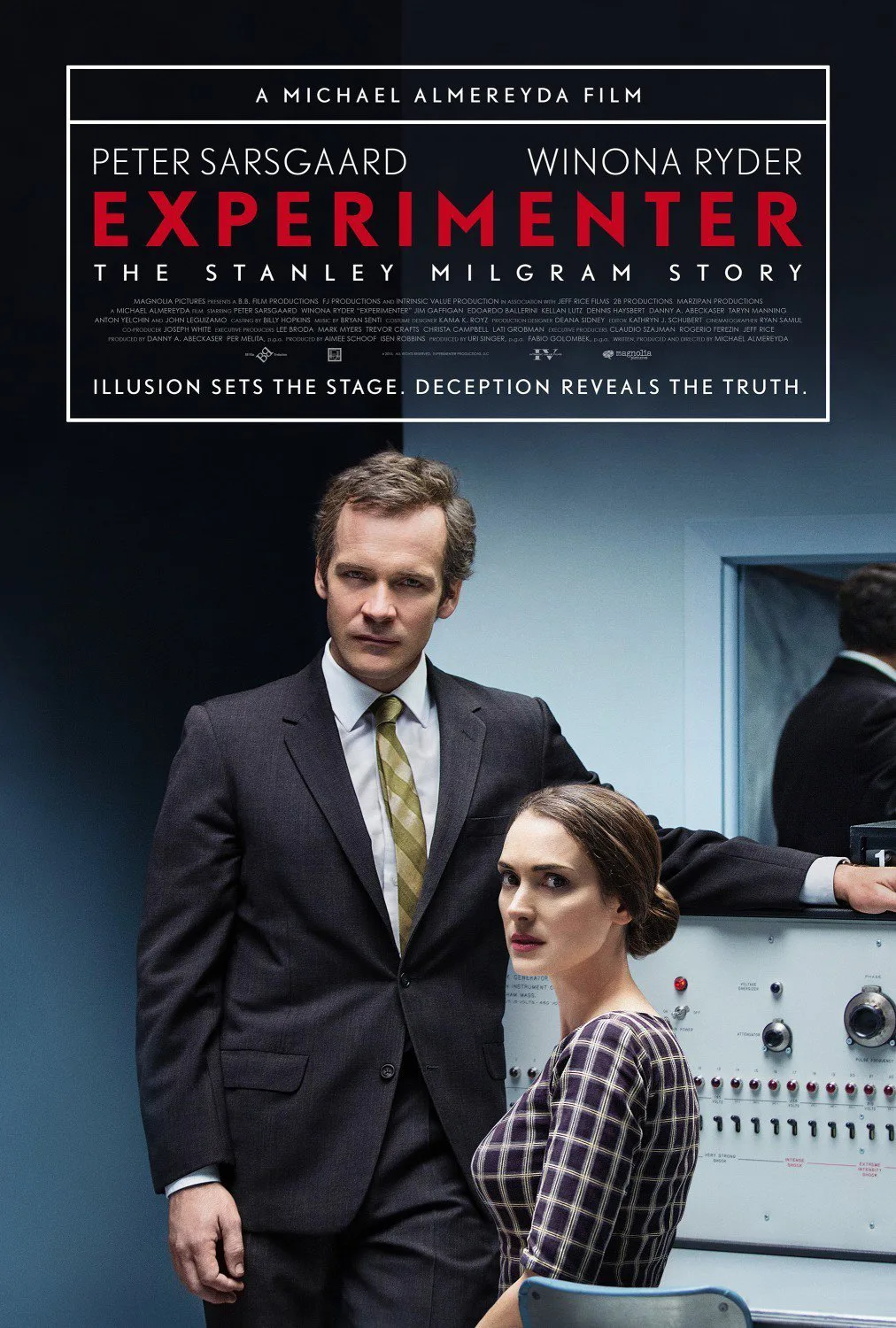

The most pleasingly cerebral of recent American films, “Experimenter” concerns Dr. Stanley Milgram (Peter Sarsgaard in an expertly shaded and intelligent performance), the creator of certain enduringly famous experiments in social psychology, which the film starts out by showing us. In a psych lab at Yale University in 1961, Milgram watches from behind a two-way mirror as an associate (John Palladino) escorts two men into a room where he explains the experiment in which they’ve agreed to participate. One man will be called “Learner” and will try to memorize answers to standardized tests. The other man, “Teacher,” will monitor the responses given by Learner (who’s out of sight) and, when he gives wrong answers, give him a series of increasingly strong electric shocks.

The nominal experiment here is a sham. In reality, Learner is not being shocked; an actor, he plays audiotapes of his voice screaming and protesting as the shocks supposedly mount in intensity. The one being tested is Teacher. How long will he go on shocking a stranger who’s begging him to stop? An overwhelming majority of people say they would stop well before the shocks reach maximum intensity. As it happened, though, both in Milgram’s original experiments and in numerous duplications of them, roughly 65 percent of subjects kept applying the shocks till the end; only 35 percent stopped at some point before.

Temporally, the significance of the Milgram Experiments cuts in every direction.

Past: When they were underway, the Israeli trial of Nazi genocide mastermind Adolf Eichmann, who claimed he was only following orders, was on American television. The son of European Jews who escaped the Nazi terror, Milgram wanted to know how ordinary people could do things that violated their conscious principles. And could it be that folks of other nations – even Americans – would submit just as Germans had? The scandalous book in which he revealed his findings was titled “Obedience to Authority.”

Present (1961): In a sense, the Eichmann trial connects the Holocaust to the era of “The Manchurian Candidate,” when Americans were so fearful of their Communist enemies that they questioned their own psychological make-up, and when an academic-scientific-military complex emerged to deal with such concerns. Needless to say, that complex didn’t disappear along with the Soviet Union.

Future: As the film shows, when Milgram’s findings become public, they spark widespread interest, with some hailing their importance while others denounce the scientist’s methods as unethical and manipulative. Their paradoxical importance continues. During the Vietnam War they are invoked to explain the My Lai massacre. Films of them are still shown to West Point cadets. Need their relevance to the post-9/11 American penchant for torture, both military and more broadly cultural, be stated?

Back to those scenes in the Yale lab. In most movies, no doubt, we would be kept in doubt about the experiment’s real nature until we’d seen at least one Learner shocked to the breaking point. But Almereyda tosses away the possibility of suspense and shows us what’s going on from the first. Filmed with a cool, Kubrickian detachment, these scenes align our p.o.v. not with the experiment’s participants’ but with the scientist’s (and by extension, the filmmaker’s). Rather than conventionally dramatic, the effect is wry, inquisitive, even darkly comic.

During this early sequence, Almereyda intercuts scenes of Milgram meeting the dancer (Winona Ryder) who will become his wife. These passages announce that “Experimenter” will concern not just the work but also the man. Yet, if this is a biopic, it’s hardly a conventional one. It seems not at all interested in probing Milgram’s psychology, to wonder why he would undertake this type of work. And, in effect, the film’s wife-and-family parts have a basically negative function in that, rather than explaining anything, simply tell us he was a fairly ordinary guy.

So, ultimately, Almereyda’s emphasis falls on his subject’s work and public life. After the famous experiments and the book that followed, Milgram becomes something of a controversial public intellectual, moves to Harvard (then later City University of NY) and concocts other experimental tests of human behavior, some very interesting but none achieving the notoriety of the earlier ones. As the career unfolds, we become aware of how much the academic-scientific-military complex intersects with the nation’s imagination on various pop-cultural fronts. Milgram himself is on television. He engages with “Candid Camera.” He watches CBS turn his life’s work in a bad TV movie, “The Tenth Level,” starring William Shatner and Ossie Davis.

As we see that monstrosity being shot, Milgram muses to the camera about his chagrin. When he thinks of turning his work into a Broadway musical, he bursts into song on a midtown street. All of which points to one of the film’s chief delights: its eclectic mix of formal stratagems and narrative modes. Almereyda has Milgram address the camera frequently, sometimes telling us of things that haven’t yet happened. He uses rear-screen projection (which serves various purposes, including evoking a bygone cinematic era), various surrealistic touches and all manner of distancing devices. His tone veers from serious to satiric to wacky to contemplative and back to serious, sometimes within a single scene.

The thread that unifies all this, one might venture, has to do with the issue of free will. The upside of Milgram’s experiments (as one of his mentors attempts to point out) was to show that at least a significant minority of people can resist unwarranted social controls. What about trying to construct an educational system and a society that grow that number? Likewise, though many people love to be manipulated by movies, how about asserting the value of works like “Experimenter,” which, in keeping the emotional temperature low and presenting us with a collage of evidence on related subjects, allows us the interpretive freedom to construct its meanings for ourselves?

No doubt, that kind of freedom is only offered us by a certain type of artist, of which Almeredya is a prime and invaluable example. From early in his career, it was clearly that he was an unusually gifted director, yet rather than allowing himself to be sucked into the mainstream moviemaking system, he has deliberately stayed on the intelligent margins, making a range of films from docs to shorts to modern Shakespeare adaptations to works that deserve the designation experimental. In so doing, he has allowed himself a creative freedom that suffuses his latest like a constant stream of mountain air. “Experimenter,” he might say, “c’est moi.”