In his autobiography, My Last Sigh, Luis Buñuel recalls a 1930s sojourn in Hollywood with affection but also bemusement. Reflecting on the predictability of Tinseltown product, he tells a story of seeing Josef von Sternberg’s “Dishonored” with one of the film’s producers. Afterward, he comments to the producer on how he’d figured out the ending in the first five minutes. The producer can’t believe it. Buñuel brings the fellow home and wakes his then-upstairs-neighbor Ugarte, who’s similarly cranky about such matters. Buñuel writes:

Grumbling, Ugarte staggered downstairs half-asleep, where I introduced him to the producer.

“Listen,” I said to him. “You have to wake up. It’s about a movie.”

“All right,” he replies, his eyes still not quite open.

“Ambience — Viennese.”

“All right.”

“Epoch — World War I.”

“All right.”

“When the film opens, we see a whore. It’s very clear she’s a whore. She’s rolling an officer in the street, the …”

Ugarte stood up, yawned, waved his hand in the air, and started back upstairs to bed.

“Don’t bother with any more,” he mumbled. “They shoot her at the end.”

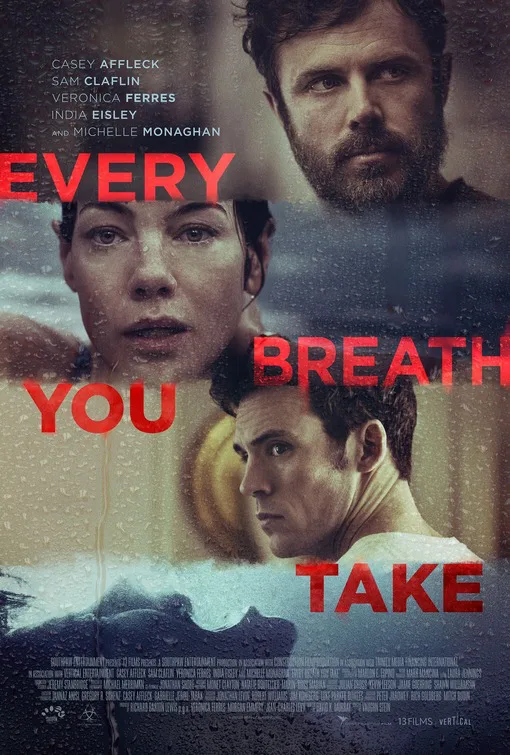

Such things still happen today. Take this particular film. It opens with a God’s-eye-view of a corner of Washington State, an open road and a big moon in the corner of the frame. Cut to a mother and cute young son in a car trading jokes. The conversation turns serious. The little boy’s dressed for hockey and expressing misgivings; the mother, who we recognize as Michelle Monaghan, says to him, “Sometimes we need to do that thing we’re scared of.”

Sometime between the moon and that line, I thought, “Fatal car accident.” And sure enough, wham, a pickup truck slams their car. It is fatal—but only for the child.

The movie shifts to some time later. The boy was Evan, and he was the only son of Monaghan’s Grace. She’s a real estate broker; husband Philip is a psychiatrist, and his daughter from a prior marriage, Lucy, is a troubled teen just recently expelled from school for drug trouble.

Played with a deliberate and eventually plodding lack of affect by Casey Affleck, Philip has performed radical therapy on a patient who he presents as a case study. His method—one of empathy and sharing, not a common thing in psychiatry as such—gets some concerned skepticism from colleagues. But Philip insists it works—patient Daphne (Emily Alyn Lind) is off her meds, happy, and creative. The only glitch is a controlling boyfriend she’s trying to wrest from her life.

But wait. A friend’s death sends Daphne into a spiral, and she commits suicide. At the scene of her death, her brother James, played by Sam Claflin, is understandably distraught. When Sam comes by Philip and Grace’s ultra-snazzy house, returning a book Philip had loaned to Daphne, Philip is moved to as James to stay for dinner, where he displays charm, explains his British accent, and discusses his work as a novelist.

So maybe the movie’s not going to be so predictable after all. It seems at this point to be heading in a direction almost like that of Pasolini’s “Teorema,” the metaphysical/political allegory in which a angel/devil played by Terence Stamp seduces a bourgeois family and gives their lives new purpose. Which would have been something different, at least.

Instead, director Vaughn Stein, working from a script by David Murray, makes a hash out of elements of Scorsese’s “Cape Fear,” Adrian Lyne’s “Fatal Attraction,” Lyne’s “Unfaithful,” and Demme’s “The Silence of the Lambs.” The predictability factor creeps back in again, even more noxiously, because the movie tries to class up its plot turns with family “drama” that doesn’t come close to camouflaging the essential joyless trashiness afoot here. What’s worse is that the film initially pretends to have some sensitivity about mental illness, but blatantly trivializes it and uses it as a crutch upon which to hang the villain’s increasingly maniacal actions.

And at the final meltdown, the sharp-eyed observer will notice poor Evan’s hockey skates in the room where it all happens. And of course they should be able to guess what they’ll be used for. Gross.