“Was all that money I made las’ year (for Whitey on the moon?) / How come there ain’t no money here? (Hm! Whitey’s on the moon) / Y’know I jus’ ‘bout had my fill (of Whitey on the moon) / I think I’ll sen’ these doctor bills airmail special (to Whitey on the moon)”

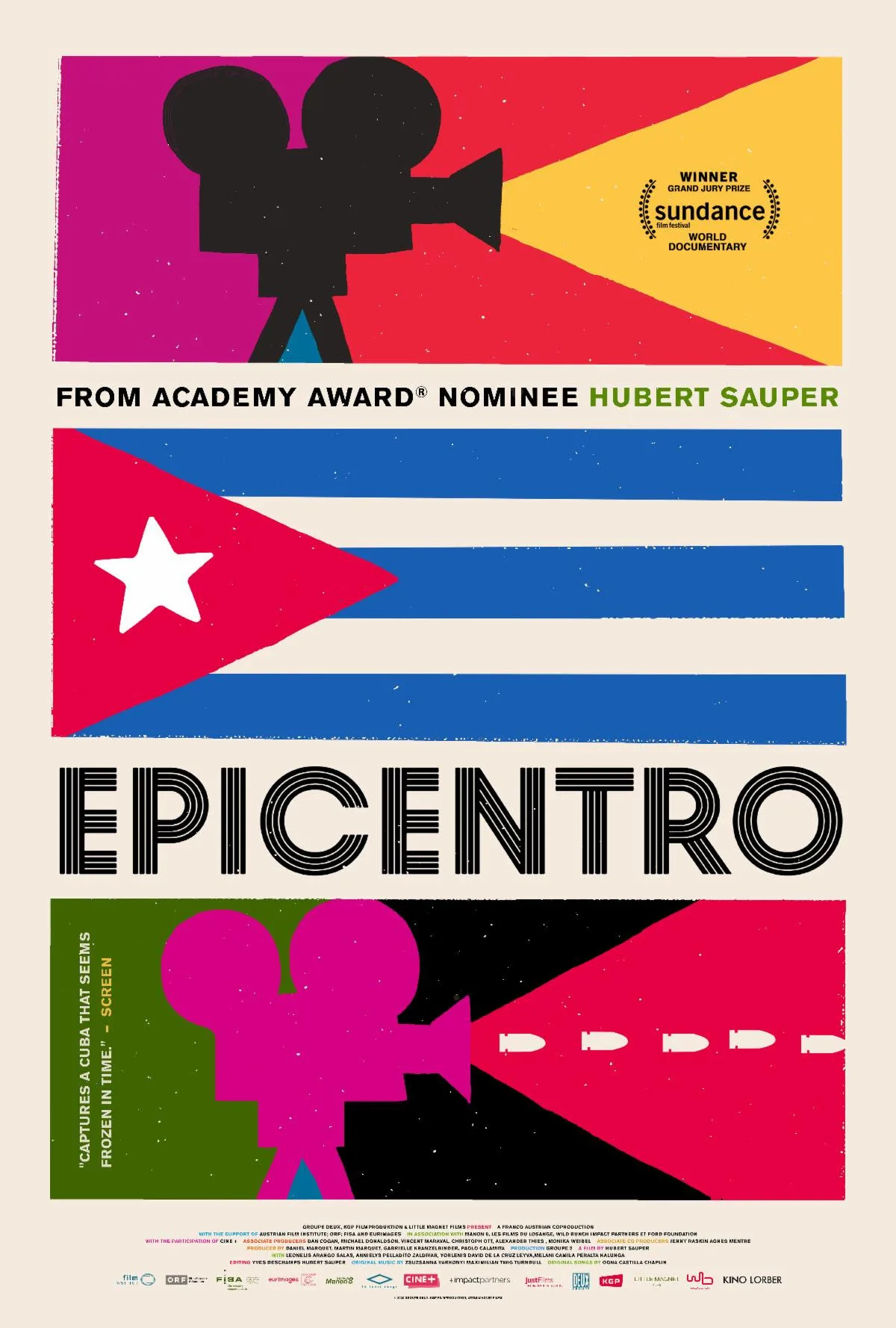

These indelibly scathing lyrics penned in 1970 by Gil Scott-Heron have lost none of their fire, as recently evidenced on the latest hour of HBO’s “Lovecraft Country,” which not only played the spoken word classic in its entirety, but also pointedly borrowed its name for the episode title. Though Scott-Heron’s words are not included on the soundtrack of director/cinematographer Hubert Sauper’s Cuba-set documentary, “Epicentro,” their fiercely indignant spirit still manages to haunt every frame, especially when its local subjects derisively observe that the moon can be included among the 900 U.S. military outposts upon which the American flag is planted. The very first was Guantánamo, the country’s small tropical island that was forced to give up its naval bases once America began its occupation, which the Cuban government still regards as illegal. In many ways, this picture serves as a spiritual successor to Sauper’s previous Sundance prize-winner, 2014’s “We Come as Friends,” where the newly independent South Sudan is promptly colonized by foreign investors, causing its citizens to point out that even “the moon belongs to the white man.”

The term “epicenter” is also a recurring one in Sauper’s filmography, as he consistently finds himself drawn to examining remote locations in the world that embody a perpetual crossroads of opposing cultures while simultaneously reflecting the past and forecasting a dire future. At once mesmerizing and self-questioning, “Epicentro” reminds us that while many great works of cinema transform the medium into an “empathy-generating machine,” as termed by Roger Ebert, it can also be used as a dehumanizing device for churning out propaganda. A few years after the Lumière brothers held the first commercial public screening of their short films, the USS Maine was blown up while on its journey to protect its nation’s interests in Havana Harbor during the Cuban War of Independence. Though the precise cause of the explosion is still debated over a century later, with much evidence suggesting that it was triggered by fire in the coal bunker, yellow journalism placed the blame on Spain in a blatant attempt at intensifying public support for the Spanish-American War. William Randolph Hearst’s notorious order, “You furnish the pictures and I’ll furnish the war,” is echoed in the phony war footage we see here, which was filmed in a bathtub with the aid of model boats and cigar smoke.

When Sauper’s ever-searching lens briefly cut to a scene from Orson Welles’ “Citizen Kane,” I was reminded of why it will forever be the greatest American film of the 20th century, apart from the fact that it was the most influential. Modeled after Hearst, Kane chillingly represents the utopian illusion of the American dream in his corrupted ideals and success forged in lies. During his interview contained in the film’s production notes, Sauper mentions that Thomas More’s novel Utopia debuted just shy of a quarter-century after Columbus “discovered” America. “I think it is amazing that the otherworld utopia—meaning a good place and a nonexistent place at once—emerged at the same moment as the ‘new world,” he marveled. The timeliness of “Epicentro” couldn’t be graver, as Americans devastated by a global pandemic that has accentuated our systemic inequities in the starkest of terms, have begun questioning the mythologized stories that have been passed down for generations and immortalized in self-righteous monuments, including those of Columbus. When a roomful of kids in Cuba see silent footage of the American flag being raised on their land as an alleged rebuke to tyranny, they angrily dub the image a mistruth. Indeed, President Theodore Roosevelt’s volunteer regiment, the “Rough Riders,” emulated the pompous traveling show skewered by Robert Altman’s “Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull’s History Lesson,” which was released and swiftly shunned in the year of America’s bicentennial.

Of all the people Sauper encounters on his filmed journeys through Cuba, none hold the camera quite like Leonelis Arango Salas, a young girl who dreams of becoming a star “like Beyoncé” and has an undeniable screen presence. She succinctly summarizes the topic of Sauper’s film as being “foreign interference, slavery and people on the street,” while explaining with meticulous specificity how the Platt Amendment gave the US the keys to her country in 1902. It’s ironic how a communist nation striving to preserve peace and justice became, as voiced in Sauper’s haunting narration, the epicenter of ingredients that formed the modern dystopian empire: slave trade, colonization and globalization of power. Though the director refuses to challenge the pro-Castro propaganda passionately recited by his subjects, his portrayal of the ease with which our emotions can be manipulated through skillfully composed fallacies speaks for itself. What appears to be a harrowing fight between Salas and her mother ends with them falling into each other’s arms, as their cries give way to laughter. Only gradually is it revealed that the adult actress in this scene is Oona Chaplin, granddaughter of Charles, who later tells Salas that by bringing stories to life, she has the ability to “create reality.” It is flat-out magical to watch Chaplin seated alongside young viewers as they bask in the glow of 1940’s eternally prophetic “The Great Dictator,” watching her grandfather’s Trumpian tyrant who toys with an inflatable model of the Earth until it pops.

To the modern-day Cubans in “Epicentro,” Trump’s face is no different from that of most American leaders stretching back to Teddy Roosevelt, who exude the desire for war and money through their very pores. The monstrous waves we see crashing upon the shores of Havana not only exemplify the apocalyptic cost of America’s inaction regarding the escalating climate crisis, they also symbolize the onslaught of tourism that threatens to submerge the country’s native culture. Though there are stretches in the film’s midsection that meander nearly to the point of indulgence, Sauper clearly intends on providing a remedy to mindless travelogues by having his subjects guide his attention rather than the other way around—even a passerby who insists on being filmed. He has stayed true to the title bestowed upon him by cinéma vérité icon Jean Rouche, who declared that the director had created—with his 1998 effort “Kisangani Diary”—“the cinema of contact.” Sauper ultimately forces us to question not only the perspective of documentaries such as his own, but how we choose to approach them, as fellow humans whose souls are connected with those onscreen, or ugly tourists not unlike those we see gawking at a local boy getting his hair cut. Rather than massage the ego of its progressive target audience, this film stares back at us with a piercingly critical gaze.