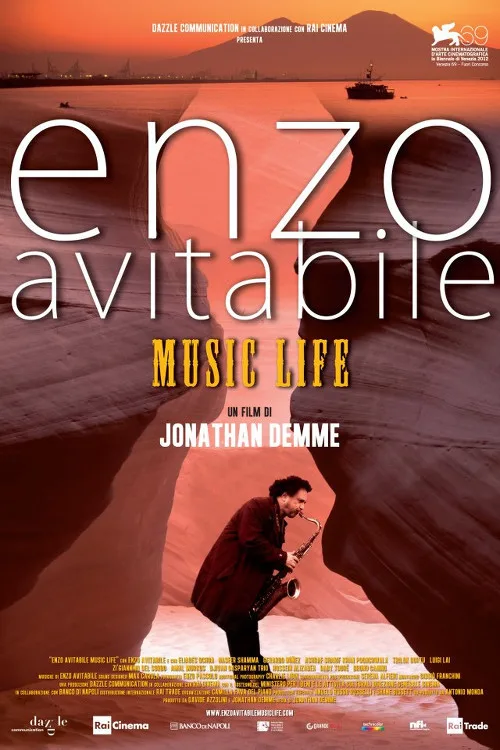

In Enzo Avitabile‘s song “Mane e Mane”, the chorus runs: “All men know it is possible to live together hand in hand”, an eloquent summing-up of Avitabile’s international outlook on life, as well as his attitude towards music. A jazz saxophonist and world-music composer, Avitabile is so famous in his native Naples that when he visits his childhood neighborhood, people cluster onto the balconies above to get a look at him, or clamor around him trying to get close. Jonathan Demme profiles and celebrates Enzo Avitabile in “Enzo Avitabile Music Life”, the most recent entry in Demme’s lengthening list of music documentaries.

Unlike his excellent Neil Young concert films, “Enzo Avitabile Music Life” feels strangely vague at times, as though Demme is still searching for a way to present his subject and hasn’t quite worked it out yet. The film feels like a first draft. But then there is the music to celebrate: Demme films an elaborate jam session hosted by Avitabile and held in a gigantic stone church with musicians from all around the world. Those jam sessions are the reason to see the film.

Enzo Avitabile is an extroverted and interesting man, with wild hair, a keffiyeh around his neck (given to him by his daughter’s Moroccan boyfriend), a dangling crucifix earring, and baggy nondescript clothes. He spills out his theories about the history of jazz (his knowledge is encyclopedic), shares his excitement with discovering Finale, a music notation software program that allowed him to compose entire symphonies and then listen to what he created, a maestro at a laptop.

He lives buried in clutter, with 300 spiral-bound music scores piling up on shelves above his washing machine. He brags about one of his daughters who just had a scientific article published. He likes to start off the day listening to “Stabat Mater” by Giovanni Pergolesi. Avitabile is interested in what connects us, in what holds us together. The foot rhythms of dancers in Sudan and Tanzania have not been properly explored by composers, he thinks, same with rare Middle Eastern scales. The Mediterranean has always been a gigantic crossroads, and Avitabile is very aware of that cultural migration and blending.

The jam session in the church is the underlying structure of the film, the event which holds it all together. Musicians from Pakistan, Armenia, Mauritania, India, Iran, Iraq, Cuba, gather together to play Avitabile’s songs. Many of them play bizarre instruments, rarely featured in orchestras, yet which have 3,000-year histories and traditions attached to them.

Avitabile’s songs are often laments about poverty and injustice, hatred and bigotry. Political in nature, they are cries for peace and understanding. He sings (and in one case does a gorgeous duet with Palestinian singer Amal Murkus) to the accompaniment of Flamenco guitar, sitar, Indian tabla drums, or the Iranian tar. The sound is phenomenal, haunting, catchy. The musicians play in a large round space, surrounded by columns and religious murals, the stone floor covered in overlapping Persian rugs. When filmed from overhead, the jam session takes on a ceremonial aspect. The musicians, often separated by a language barrier, communicate easily through the music. The collaboration is intense and joyous.

While Demme’s camera follows Enzo on a trip down memory lane, and it is occasionally interesting, those sections were the least successful of the film. There are intriguing details dropped in our path, usually by Avitabile himself (for example, he lost his sight for a couple of years, and had to have two cornea transplants), but they remain unconnected fragments. We know he recorded with Tina Turner (a photo of the two of them dominates his study), but all we learn about that time in his life is that he appears to have converted to Buddhism, but then after his wife died he went back to what he calls “his brand” of Christianity. He is eloquent on James Brown and the way Brown’s gospel roots morphed into a secular kind of devotion which Avitabile found inspiring. Avitabile is one of those people who can barely speak without saying something interesting, but the fragmentary nature of all the biographical stuff was frustrating, especially when compared to the great liveliness and intensity of the musical scenes.

Although Avitabile is so famous in his homeland that people shout out his name as he walks by, and although he has recorded with the likes of Tina Turner and James Brown, his name is not known to most American audiences. Demme’s film, first draft though it may be, could change that.