A commercial airliner leaves for Honolulu, Hawaii from Incheon, South Korea. The flight’s passengers are held hostage by Jin-seok (Yim Si-wan), a disgruntled biologist who unleashes a deadly homemade virus just because “It seems like fun!” That’s the purely fictional setup of the bathetic Korean disaster pic “Emergency Declaration,” a lumbering and desperate ode to our common humanity that also tries to scare and thrill viewers into submission.

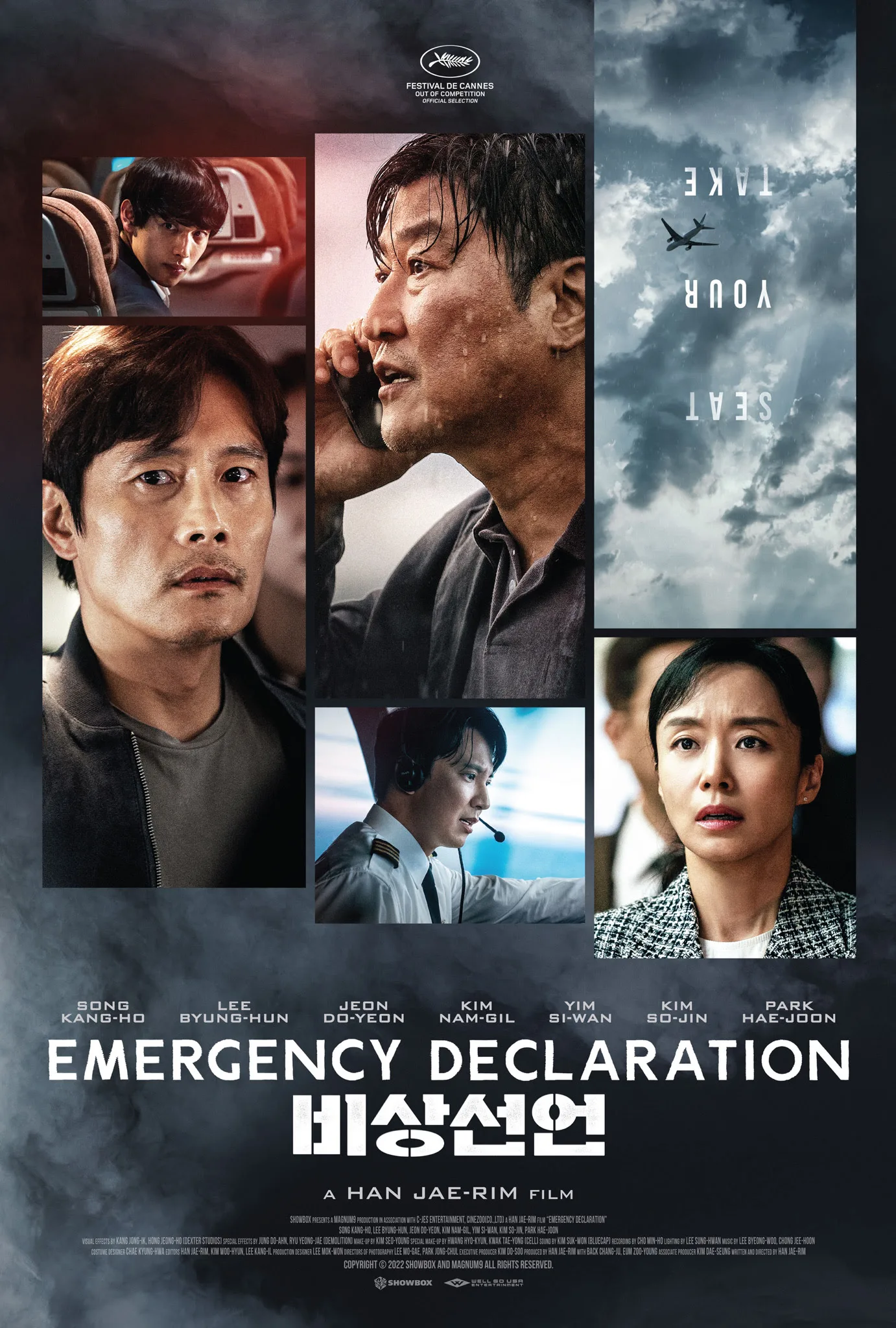

Writer/director Han Jae-Rim’s hostage thriller isn’t based on real events, but it’s still presented with the a queasy sort of naturalism that brings to mind Paul Greengrass’ “United 93”: lots of handheld photography, a half-gloomy, half-hazy color palette, and way too much dead air. The casting of three marquee-topping Korean stars—Jeon Do-yeon, Lee Byung-hun, and Song Kang-ho—also hints at the movie’s pandering nature as a feel-good tragedy about a realistic crisis.

The only thing consistent about “Emergency Declaration” is how hard Han (“Rules of Dating”) and his collaborators try to work over viewers, especially by way of the movie’s braaahm-heavy, Hans Zimmer-style score and its heart-string-yanking plot contrivances. The film’s development may have started in 2019, but its mid-pandemic production and release still makes its hokey celebratory narrative seem premature and sometimes offensive.

Almost everything in “Emergency Declaration” seems calculated for maximum affect, from its weak scare tactics to its unconvincing you-are-there aesthetic. First the movie trails after sweaty detective In-ho (Song) as he chases after Jin-seok and tries to stop his murderous plot. The emotional stakes are clear, but ultimately immaterial: In-ho’s wife (Woo Mi-hwa) is on Sky Korea flight K1501, and so are a number of narratively essential, but otherwise undeveloped supporting characters, including co-pilot Hyun-soo (Kim Nam-gil) and flight attendant Hee-jin (Kim So-jin).

A few establishing scenes half-heartedly establish how many other people are on board flight K1501, but the first 40 or so minutes of “Emergency Declaration” mostly concern the psychopathic Jin-seok. First we see Jin-seok harass and curse out a meek Sky Korea employee, who refuses to tell him how many people are flying to Hawaii. Then we follow Jin-seok as he stumbles into concerned father Jae-hyuk (Lee) and peppers him with awkward questions about his shy young daughter Soo-min (Kim Bo-min), who suffers from bad eczema.

When Jin-seok’s not releasing a deadly virus in an airplane bathroom, he’s answering questions with questions and generally needling anyone who’s off-put by his creepy behavior. Outside the plane, In-ho discovers that Jin-seok used to torture animals for “pleasure,” and also experimented on lab mice to create a homemade plague that can mutate and spread among humans very quickly. Inside the plane, a sweaty Jin-seok explains to his victims that he attacked them because there’s no way for a commercial flight’s passengers to escape once they’re airborne. Jin-seok’s backstory is so florid and his dialogue is so intensely unpleasant that you almost forget that “Emergency Declaration” is also vaguely concerned with the triumph of the human spirit.

The flight’s crew members and passengers fight back panic while they plan a course of action with calm, noble public officials, particularly Transport Minister Sook-hee (Jeon), but also In-ho and his fellow police officers. These main protagonists don’t really have personalities beyond whatever the scene demands of them, whether it’s plotting an emergency landing in Seongmu, or swapping out one in-flight meal for another. Hee-jin, Jae-hyuk, and Sook-hee all inevitably assert themselves, but their heroic actions are often just as hammy and unbelievable as Jin-seok’s cartoonish villainy.

At one point, Lee’s character delivers a flowery, long-winded speech that explains why he, acting on his fellow passengers’ behalf, has selflessly chosen to take evasive actions. Jae-hyuk’s explanations sound as pompous and self-righteous as the worst Oscar acceptance speech, especially when he explains that “because we are human … there are things that only we can do. Now we intend to make a decision for everyone’s sake.” A few canned reaction shots suggest that Jae-hyuk’s fellow passengers have already resigned themselves to their fate since they, too, are passively listening to Lee.

In another key scene, K1501’s passengers use their Wi-Fi enabled phones to reassure their loved ones and resolve their unfinished business. These fragmentary, pseudo-banal exchanges are not only emotionally stillborn, but also visually stifling since they’re presented as a series of frame-within-frame video chat calls. We look up at tear-stained and lens-distorted faces and listen to mawkish conversations about grandma’s cooking—“I’m sorry for saying your food tasted bad”—and rainy day savings: “Behind there, I hid some money. Buy some candy.”

After a few overheated exchanges, the camera’s visual field blinks out of existence after the people on-screen are reduced to a smaller frame within the frame. Then the next scene begins, because that plane has to come back to earth somehow, in the name of humanity and by any means necessary.

Now playing in theaters.