George Khan is like that performer on the old Ed Sullivan show, who tried to keep plates spinning simultaneously on top of a dozen poles. He runs from one crisis to another, desperately trying to defend his Muslim world view in a world that has other views. George is a Pakistani immigrant to England, living in Manchester in 1971 with his British wife and their unruly herd of seven children, and his plates keep falling off the poles.

As the movie opens, George glows proudly as his oldest son goes through the opening stages of an arranged marriage ceremony. The bride enters, veiled, and as she reveals herself to her future husband, we see that she is quite pretty–and that the would-be husband is terrified. “I can’t do this, Dad!” he shouts, bolting from the hall. George is humiliated.

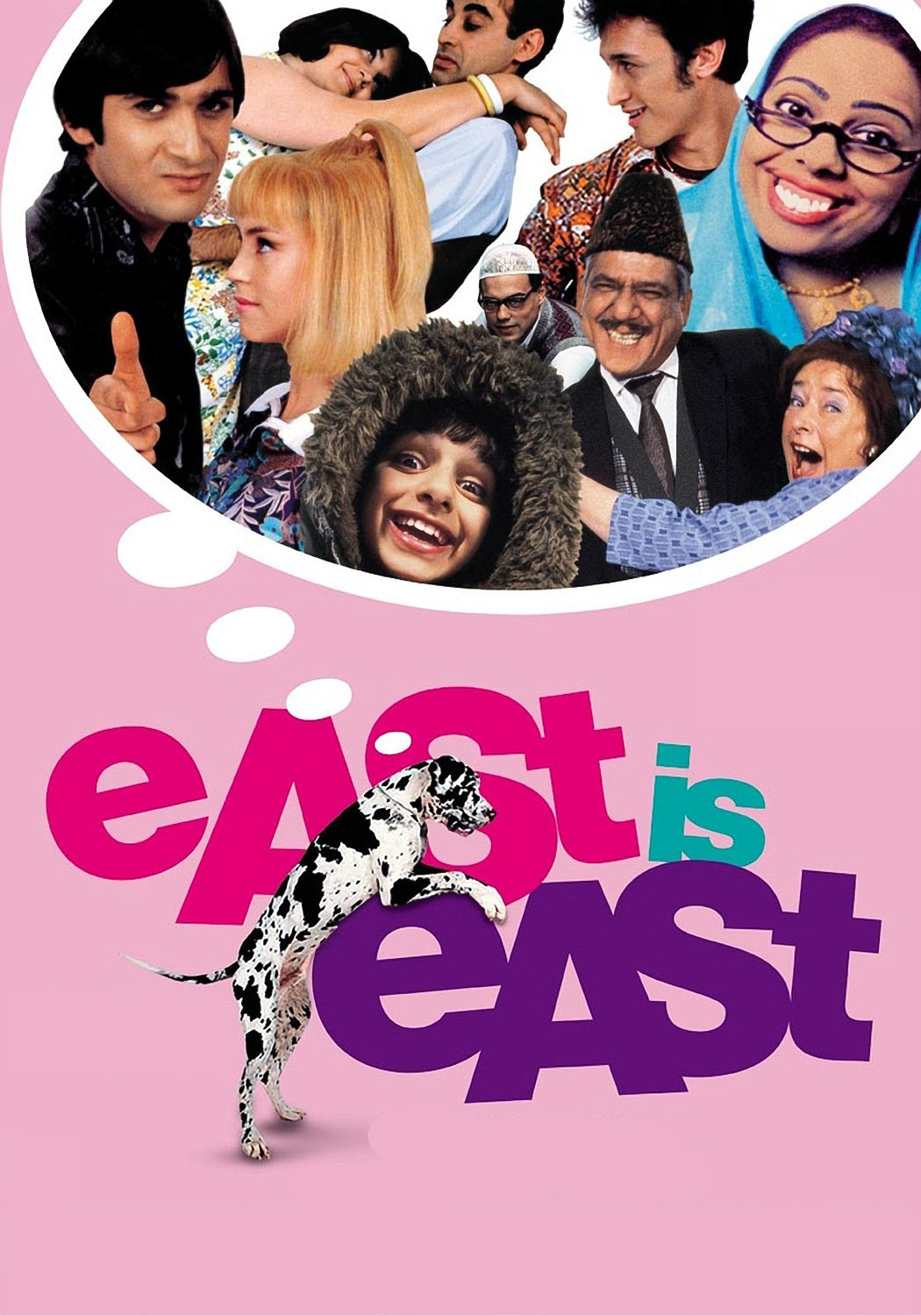

George is played by Om Puri, as a mixture of paternal bombast and hidebound conservatism. His wife, Ella (Linda Bassett), has worked by his side for years in the fish and chips shop at the corner of their street of brick working-class row houses. After their oldest son flees, they are left with a full house, including a neighborhood ladies’ man, a shy son, a would-be artistic type, a jolly daughter and little Sajid, the youngest, who never, ever takes off his fur-trimmed parka. There is even a son who agrees with his father’s values.

Puri plays George Khan as the Ralph Kramden of Manchester. He is bluff, tough, big, loud, and issues ultimatums and pronouncements, while his long-suffering wife holds the family together and practices the art of compromise. His own moral high ground is questionable: He upholds the values of the old country, yet has moved to a new one, taken a British wife although he left a Muslim wife behind in Pakistan, and is trying to raise multiracial children through monoracial eyes.

There’s rich humor in his juggling act. His family is so large, so rambunctious and so clearly beyond his control that it has entirely escaped his attention that little Sajid has never been circumcised. When this lapse is discovered, he determines it is never too late to right a wrong and schedules the operation, despite the doubts of his wife and the screams of Sajid. And then there is the matter of the marriages he is trying to arrange for his No. 2 and No. 3 sons–oblivious of the fact that one of the boys is deeply in love with the blond daughter of a racist neighbor who is an admirer of Enoch (“Rivers of Blood”) Powell, the anti-immigration figurehead (who has been confused in some reviews, perhaps understandably, with the 1930s fascist leader Oswald Mosley).

Of course the neighbor would have apoplexy if he discovered that his daughter was dating a brown boy. And George would have similar feelings, although more for religious reasons. One purpose of the rules and regulations of religions is to create in their followers a sense of isolation from non-believers, and what George is fighting, in the Britain of 1971, is the seduction of his children by the secular religion of pop music and fashion.

“East Is East” is related in some ways to “My Son, the Fanatic,” another recent film starring Puri as an immigrant from Pakistan. In that one, the tables are turned: Puri plays a taxi driver who has drifted away from his religion and falls in love with a prostitute, while his son becomes the follower of a cult leader.

In both films, the tilt is against religion and in favor of romance on its own terms, but then all movie love stories argue for the lovers. Two recent Oscar winners, “Titanic” and “Shakespeare in Love,” were both stories of romance across class lines, and “American Beauty” and “Boys Don't Cry” were about violating taboos; it could be that movie love stories are the most consistently subversive genre in the cinema, arguing always for personal choice over the disapproval of parents, church, ethnic groups or society itself.

If there is a weakness in “East Is East,” it’s that Om Puri’s character is a little too serious for the comedy surrounding him. He is a figure of deep contradictions, trying to hold his children to a standard he has eluded his entire life. Perhaps the real love story in the movie is the one we overlook, between George and his wife Ella, who has stood by him through good times and bad, running the fish shop and putting up with his nonsense. When he blusters that he will bring over his first wife, who understands his thinking, Ella tells him, “I’m off if she steps foot in this country!” But he’s bluffing. His own life has pointed the way for his children. It’s just that he can’t admit it, to them or himself.

Note: This is a provocative film, useful for discussions between parents and children. The “R” rating is inexplicable.