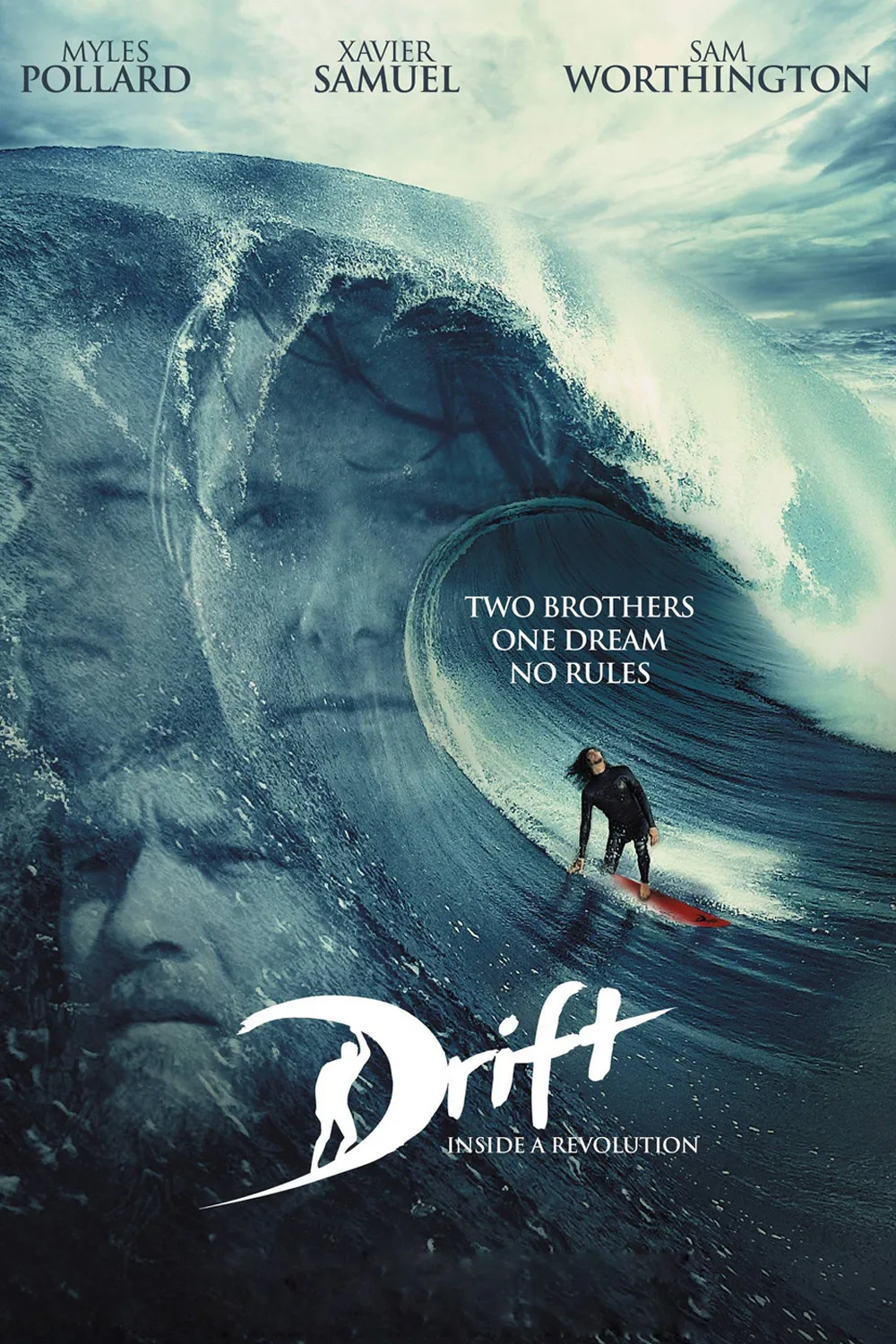

If there are “eight million stories in the naked city,” then there are eight million stories in surfing, too, and “Drift,” a new film from Australia, is one of them. Uneven and lacking in focus, “Drift” tells the story of the burgeoning surf-gear business in Australia in the 1960s and ’70s. Companies like Rip Curl, Billabong, and Quiksilver started as local brands and soon exploded to dominate world-wide (they still do). Who were the guys who revolutionized surf board design? How did that revolution happen? Co-directed by Ben Nott and Morgan O'Neill (who also wrote the screenplay), “Drift” stars Sam Worthington, Myles Pollard, and Xavier Samuel as three Australian surfers who open a backyard surf-gear business in the 1970s. They face problems getting loans, problems with drug trafficking, problems with girls, as well as intermittent attacks of existential angst. The acting is quite good, natural and fresh, and the surfing footage is magnificent. “Drift,” though, is a weird mix, and not always successful.

Jimmy (Xavier Samuel) and Andy (Myles Pollard) are brothers whose mother (Robyn Malcolm) works as a seamstress to make ends meet. Her sons work in a local mill and surf on their days off. Jimmy is good enough to win local surfing competitions but it certainly isn’t a career. A scruffy guy named J.B. (Sam Worthington) drives around Australia’s wild Western coast, living in a camper van painted like Ken Kesey’s crazy bus, with the words “NOWHERE FAST” unfurling across the top. He supports himself by taking photographs of surfers from time to time, and his stuff is featured in magazines. But he has scorn for “The Man,” and prides himself on not being owned by anyone. Traveling with J.B. is Lani, a Hawaiian woman (played by Lesley-Ann Brandt) who befriends the Kelly brothers. The business starts to take off.

Many surfing movies run along the expected sports-formula narrative, with an underdog coming from behind to win the big competition, surf the fiercest wave, beat the odds. “Drift” succumbs to some of those formulaic elements, especially when it comes to the character of Lani, whose only purpose is to be a purveyor of pep talks to the boys, as well as a quasi-love-interest and, in one scene, a damsel in distress. There’s a scary ex-con in town who seems to take offense to the Kelly brothers’ endeavor, and there is a scene straight out of Roger Corman where the ex-con and his threatening buddies roar into the middle of a happy barbecue on their motorcycles being threatening for no apparent reason.

The Kelly brothers deal with the unimaginative and conservative resistance of local bankers who refuse to loan them money. Surfing is just a hobby, you see, and the Kelly boys are seen as losers who need to get a job. All of this Individual vs. The Man stuff is handled in a ham-fisted way; many of the scenes lack life and energy. It’s unfortunate, because Myles Pollard is such a compelling and natural presence. He makes every scene seem real merely by his reaction shots, the openness of his face, his charm and charisma. He’s wonderful.

Andy Kelly is the visionary. He believes that there is a market for the shorter boards meant for big waves, and he believes that big-wave surfing is where the industry is headed. He doesn’t think of becoming a millionaire. It’s just that he knows he has a good idea, and he’d like to make money from surfing somehow. “Drift” has an eccentric and gritty appreciation of the entrepreneur and the nuts and bolts of starting a business. “Drift” is about sitting in offices, drawing up plans, finding good real estate for your storefront. While these scenes are sometimes interesting, you keep wanting them to get back out into the water. Surfing films are often about the glory. “Drift” is not.

The glory, though, comes in the cinematography. Geoffrey Hall did the photography for the film. “Drift” did not have a big budget, and they shot in 32 days. None of the enormous waves barreling down on the camera were created with visual effects or tweaked digitally. All three main actors grew up surfing and were comfortable in that often-dangerous environment. There is one sequence that has to be seen to be believed. The three tool out in an inflated boat to try to tow themselves onto a notorious break of 30-to-40 foot waves. As J.B. says to Jimmy, “The problem isn’t how to ride that wave. The problem is catching it.” The waves rear up as massive building-sized monsters, and the sense of danger and adrenaline in the three actors is palpable. There are no do-overs with such a scene. It’s an incredible feat of filmmaking, and refreshing if you love good surf movies.

In “Riding Giants,” the 2004 surfing documentary, legendary surfer Greg Noll talks about the surfing movies in the 1960s, and mocks how the actors would be sitting on surf boards in what looked like a flat pond waiting for a wave, and then suddenly be fake-riding a big wave. Noll shakes his head in disgust and says, “It made me want to puke.” “Drift” gives you the extreme pleasure of knowing that what you are seeing, the waves, the foam, the mammoth breaks, the surfing itself, is real. If only there were more of it.