What Bruce Lee had that made him a star, apart from his martial arts skills and passably good looks, was a joy of living. He brought spontaneity and humor to a genre that had previously been manufactured mostly out of threats and scowls, and by the end of his life he seemed poised for the sort of international stardom now enjoyed by Schwarzenegger and the other box office action heroes.

But he died young, in circumstances that seem as mysterious in this movie as in his life. It is invariably ominous in any biopic if, toward the end of the running time, the hero complains of a headache.

“Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story” concludes that Lee’s terminal coma was caused by unexplained natural causes, but the movie offers a more fanciful possibility: He was finally hunted down by the fearsome warrior who haunted his nightmares.

Lee did believe in the dreams, and even dressed his baby son, Brandon, as a girl, to outwit the demons. All silliness, of course, except that now Brandon Lee is dead, too, long before his time. The timing of the release of this film, so soon after Brandon’s shooting death on a movie set, is both ironic and eerie. The movie goes to some lengths to emphasize the positive side of Bruce Lee’s life, but now the ghost of his son haunts his memory.

“Dragon” is based on Bruce Lee: The Man Only I Knew, the autobiography of Linda Lee Cadwell, Lee’s wife, played here by Lauren Holly. It traces his immigration to America, his early days as a karate instructor, his breakthrough in a short-lived TV series, and his eventual emergence as a movie star just as his life was nearing its end. Some old scores are settled: The hit series “Kung Fu” was Lee’s original idea, we learn, but David Carradine starred in it because of the network’s reluctance to cast an Asian. But mostly “Dragon” is a rags-to-riches story.

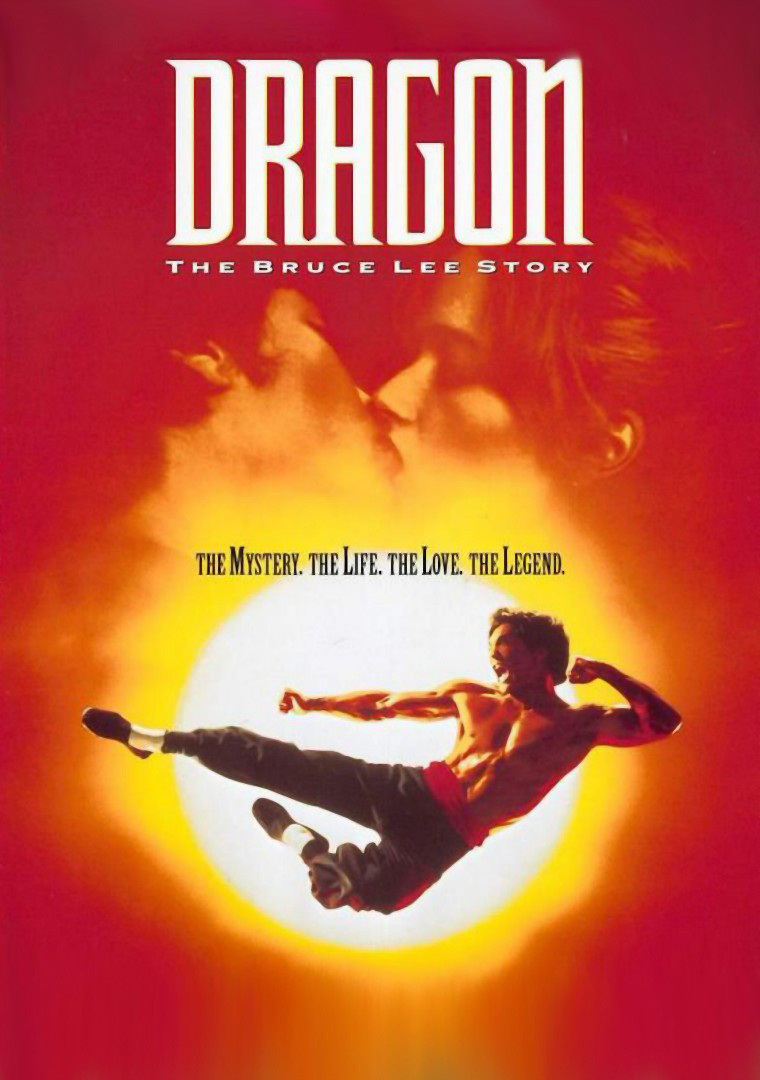

Lee is played in the film by Jason Scott Lee (no relation), a gifted young actor who also stars in the current “Map Of The Human Heart.” He brings some of the same exuberance to the role that audiences enjoyed in Bruce Lee’s films. Flying through the air, defying gravity and logic in his martial arts moves, both Lees use film to give them power over time and space. You cannot do in real life most of the things the characters in these movies do, because of the unfortunate restrictions imposed by Newton’s Laws, but what the heck: It’s fun to watch.

The movie follows the time-honored tradition of all show biz biographies by providing a character who “discovers” the hero. In this case, it’s a producer played by Robert Wagner, who defies the then-current wisdom to see that Bruce Lee had the potential to become a star.

What Lee and his producers could not have known was that martial arts movies would grow into an important Hollywood genre, transcending the Western and the musical in recent years, and providing employment for Steven Seagal, Jean-Claude Van Damme and others. It still remains true, unhappily, that most of the chop-socky heroes are white; no Asian star has really made an impression on the American market since Lee’s death, and now the chances of his Asian-American son have been destroyed.

“Dragon” contains several martial arts sequences, all of them very well done (Jason Scott Lee makes a convincing student of the master’s skills). None of these scenes, of course, address the central contradiction of most karate production numbers: Why, since the hero is always outnumbered, do his oppponents approach him one at a time and get creamed, when they could easily gang up on him and overwhelm him? I guess maybe the answer is, because then there wouldn’t be a movie. A fairly good answer, I suppose.