“Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot” takes its title from a punchline for a cartoon panel that depicts a cowboy posse beside an empty wheelchair in a desert. That unabashed non-PC sentiment epitomizes the sort-of-funny, kind-of-sad shaggy mood of this biopic about its creator, John Callahan. The Portland-based loafer, lothario and lush forever altered his life in 1972 by allowing Dexter, a fellow drunkard and self-proclaimed “cunnilingus king of Orange County” (Jack Black, bedecked with massive sideburns), to take the wheel of his baby-blue VW Beetle. The resulting crash left Callahan a quadriplegic at age 21 while Dexter walked away without a scratch. The rest of Callahan’s story is primarily focused on his long and winding road to sobriety via a 12-step therapy group, adapting to his new physical circumstances and his developing talent for darkly humorous drawings with provocative captions that both wryly amuse and deeply offend.

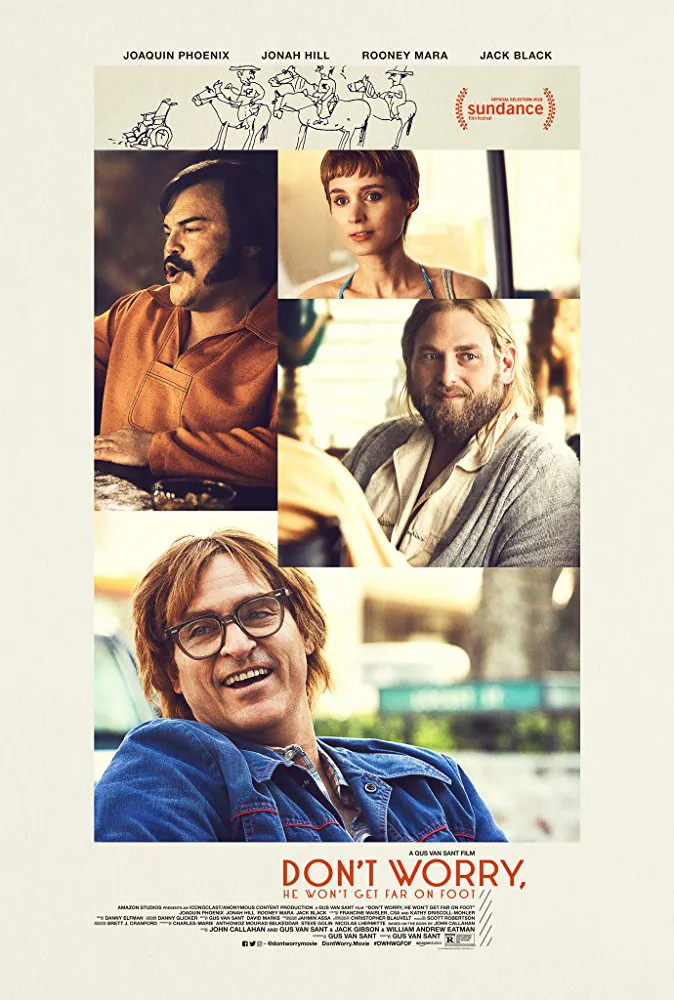

As movies about misanthropic outsider artists with medical issues go, “Don’t Worry” doesn’t come close to the superb “American Splendor” with Paul Giamatti as the irascible Harvey Pekar. When compared to the subset of top-tier films about men in wheelchairs, including “Coming Home,” “My Left Foot,” “The Diving Bell and the Butterfly” and “The Theory of Everything,” it falls somewhat short. And, at age 43, as good of an actor as Joaquin Phoenix is, he looks too old as the young, out-of-control Callahan (who physically appears to be modeled on an orange-haired version of Jeff Spicoli). Also bothersome is how his growth as a cartoonist, the most interesting fact about Callahan, becomes secondary to his biggest emotional obstacle: the rage he harbors for his unwed mother, who gave him up for adoption as a baby.

Robin Williams, acknowledged in the credits, brought the project based on Callahan’s same-titled 1989 memoir to filmmaker Gus Van Sant two decades ago with the hopes of playing the lead and producing. Who knows what the result would have been if his “Good Will Hunting” star was the one zipping along in his motorized wheelchair, traffic and curbs be damned. Perhaps humor would take more prominence over self-pity. That Van Sant kept his commitment to the late comic is commendable. But Van Sant the screenwriter does a disservice to the material by constantly chopping up narrative strands into bite-size chunks and later circling back to key incidents—the night of the accident, group recovery meetings, a bunch of teen skateboarders who rescue Callahan after he tumbles out of his chair, an inspirational onstage speech that he gives to fellow addicts. It’s like having a waiter replace your plate of food with another one before you get to finish it and later brings the original plate back after it has gone cold.

To continue this food metaphor, the sides tend to upstage the main course—namely, Phoenix. The colorful sideshow of characters in his AA-like group is straight out of a John Waters movie. Rocker Kim Gordon of Sonic Youth shows up as a no-longer Valium- addicted desperate housewife. German acting icon Udo Kier’s silver-haired presence is a gift enough. But one participant dominates these gatherings, a plus-sized force of nature in the guise of musician Beth Ditto, who dares to call BS on Callahan as he refuses to hold himself accountable for his sorry state.

But if anyone outshines Phoenix, it is Jonah Hill. He’s nearly unrecognizable with a slimmed-down bod, sleek blond Jesus locks and a penchant for caftans, gold chains and cigarette holders as the group’s laid-back trust-fund-kid guru, Donnie. This out gay man is full of Zen grace as he lovingly calls his acolytes “piglets” while patiently waiting for Callahan to be deserving of his services as his personal sponsor. That includes forgiving those who trespassed against him, most notably Black’s Dexter, which leads to a reconciliation scene that is one of the film’s highlights mostly because it is raw and very real.

I noticed that male critics are head over heels for what they consider a return to form by Van Sant, whose last great film, 2008’s “Milk,” collected eight Oscar nominations, including earning Sean Penn a second acting Oscar. But while there is some solid gnarly stuff here as addiction dramas go, nearly all the women onscreen are defined by their ties to Callahan. I don’t know why Rooney Mara shows up in a shadow of a role sporting Mia Farrow’s manic pixie haircut from “Rosemary’s Baby,” first as Callahan’s physical therapist and later as a flight attendant and his lover. Carrie Brownstein of “Portlandia” is relegated to being his disagreeable welfare rep. And then there is his female sex adviser who suggests he should ask his pretty young nurse to sit on his face and we get to see what that would look like.

Callahan, whose drawings ran in such notable publications as The New Yorker, Penthouse and National Lampoon, was 59 when he died in 2010. As someone who refused to put the disabled on a pedestal, who knows what he would think of Van Sant’s treatment of his story that grows ever more uplifting as it rolls along. All I know is that someone who drew a panhandler wearing a sign with the message “Refuse to ‘Have a Nice Day!’” might exhibit a few qualms.