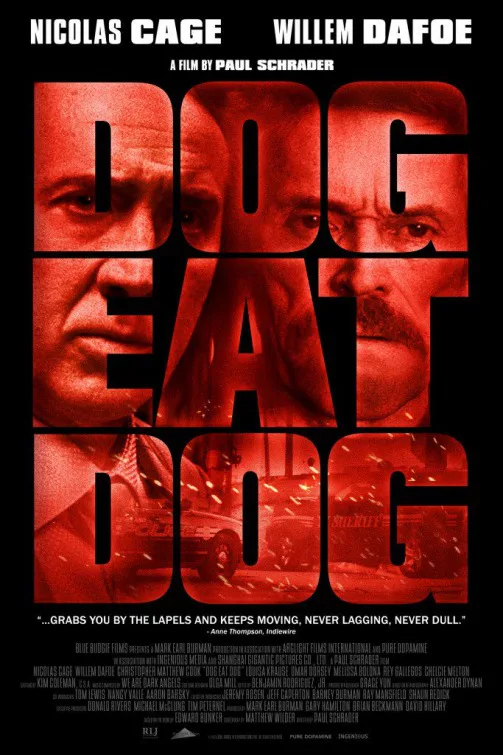

Unpleasantly deranged crime thriller/black comedy “Dog Eat Dog,” the latest melodrama directed by Paul Schrader (“The Canyons,” “American Gigolo“), is the worst kind of bad movie: the kind with an intelligence that doesn’t excuse its lifelessness. “Dog Eat Dog” kicks off with an amped-up, hallucinatory action scene that places us squarely in the tortured head space of a drug-using thief named Mad Dog (Willem Dafoe). Mad Dog is one of three ex-cons who generically plan one last big score but predictably run into problems. Mad Dog is at his most manic when we meet him: he does enough drugs to sedate three adult elephants, then murders two women in cold blood while distracting noises, like the sound of a schoolgirl leaving an inane voice-message about a cupcake-related homework assignment, crowd his psyche. This is the clutter and confusion that Mad Dog, one of three ex-cons, has to power through after spending years in prison. He’s lost touch with reality, and apparently so has Schrader. “Dog Eat Dog” may be successfully alienating, but that doesn’t mean it’s entertaining, thoughtful or even successfully provocative.

Most of “Dog Eat Dog” is relatively sedate compared to its toxically over-the-top opening scene. This is partly because Mad Dog is not the film’s main character, but rather one of two foils for Troy (Nicolas Cage), a deluded, Humphrey Bogart-worshiping crook who imagines his life as a film noir. Troy even keys us into his self-made narrative through noir-ish voiceover narration, and classically-composed (ie: not hand-held photography) camera angles. Troy works with Mad Dog and Diesel (Christopher Matthew Cook) on one last score—kidnapping a rich gangster’s baby daughter—because Troy’s convinced that it’s only a matter of time before he and his friends are incarcerated again. Troy’s got a few screws loose on this score, as an establishing flashback reveals when he, after being denied bail, steals a court officer’s gun and flees from the judge’s chambers. So you can’t really trust Troy’s judgment, even though he is the most emotionally stable member of his crew.

Then again, Schrader never gives you reason enough to care about Troy, Mad Dog, or Diesel’s stories since all we have to go on are vague, character-defining episodes where they blow up and then quickly try to regain their composure. The “one last score” narrative is, in that sense, predictably about redemption, but that’s why it’s doomed from the start. Mad Dog asks Diesel if he thinks people can change, and Schrader and screenwriter Matthew Wilder’s answer might as well be tattooed on Cook’s forehead: Hell no!

Dafoe and Cage may bring a charming level of world-weariness to their otherwise dim-bulb hothead characters. But one can’t help but feel that these characters are doomed by their bullish optimism. Here are men who expect good things to happen for them despite the fact that they flat-out refuse to re-integrate back into post-prison society. Mad Dog gets caught by his girlfriend looking at internet porn, presumably because the novelty of having instant access to the stuff appeals to him. He later blows up at a shady masseuse who, while giving Mad Dog a sexual favor, distractedly starts texting on her cell phone. Post-prison life may be full of amenities, like drugs, sex, and technology, but these things are distractions. There’s nothing to these guys’ lives outside of partying and pulling off jobs, so why not retreat into fits of noirish fantasy?

Well, for starters, being stuck with thuggish characters for 90 minutes is a chore when the only attractive thing about these characters is their comically myopic selfishness. This is, after all, a Paul Schrader film. Schrader’s dramas often concern characters who define themselves with impossible tasks knowing that their self-assigned missions are essentially suicidal. These are typically grim, haunted figures who are trapped by circumstances that they feel are beyond their control.

So while it’s not surprising that Troy’s group decides, in his words, to make like “samurai” and follow through without deviation on their heist plan—no matter how doomed it seems—it is frustrating to be constantly reminded of how (literally) impotent these guys all are. Mad Dog is an ostensibly comic figure because he’s a confused macho-type who can’t ejaculate on command for the above-mentioned masseuse. Diesel is smooth enough to lure a woman into his hotel room, but he freaks out and drives her away after he wrongfully insists that she knew that he was an ex-con. And Troy makes lavish passes at disinterested prostitutes who are so hatefully caricaturish—fake breasts, airhead syntax, and a constant fixation with money—that you can’t help but feel bad for the actresses playing them. You can see through these guys from a mile away because there’s never any substance to them.

You also can’t help but groan when “Dog Eat Dog” goes off the rails during its concluding 20 minutes, and returns to the emotionally unsteady status quo of its opening scene. Cage carries the film during this stretch with a characteristically bonkers performance, but by this point, you’re not watching a man devolve into a state of cartoonish hysterics, but rather an under-developed antihero whose pathetic downward spiral just isn’t funny and/or compelling. If you’re hankering for a dumb, mean-spirited drama that goes nowhere you haven’t already been before, “Dog Eat Dog” was made just for you.