The guitarist Django Reinhardt brought a European accent to jazz music. But just as jazz was an African-American invention, the party music of an oppressed race, Reinhardt’s contribution derived from the perspective and experience of the outcast. Reinhardt, born in Belgium, was a Romany gypsy, and his fiery but fleet and light guitar style, which he applied to an American idiom, was heavily indebted to the gypsy tradition. Like Charlie Parker, his influence and importance were directly inverse to his lifespan: Reinhardt died of a stroke at the age of 43, in 1953. (Parker died at age 34 in 1955.)

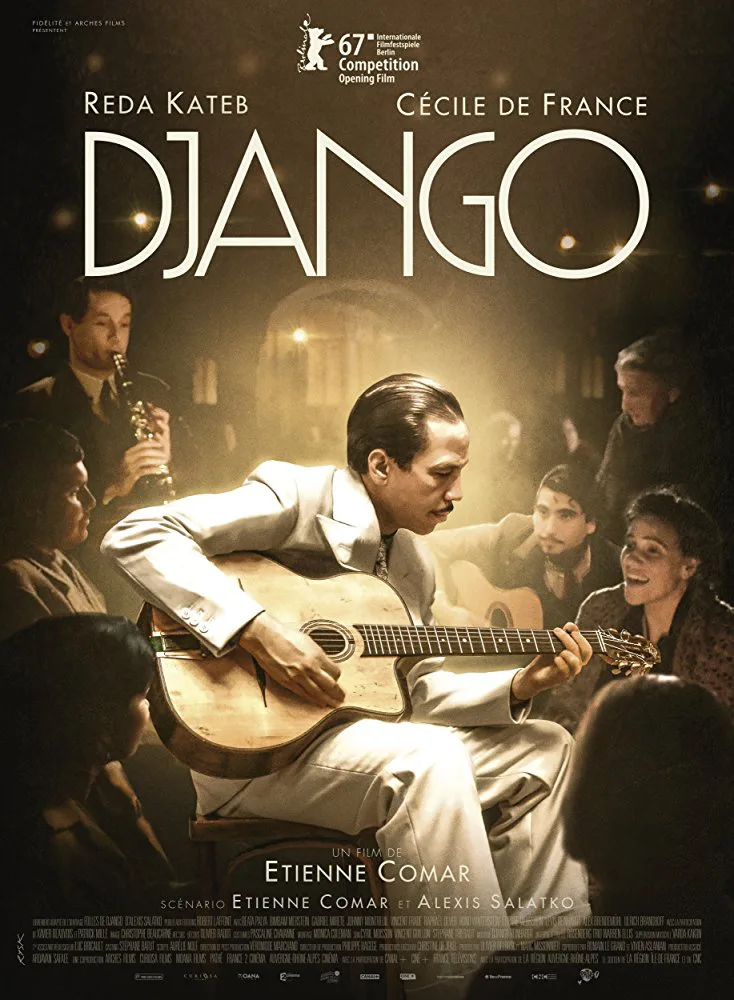

“Django,” directed by Etienne Comar from a script by Comar and Alexis Salatko, from whose novel the movie was adapted, treats only a couple of years in Reinhardt’s life, depicting his troubles in Nazi-occupied France during World War II. The movie opens as some German soldiers wipe out a gypsy encampment in Ardennes. It’s a brutal scene, as joyous music is drowned out by gunfire. The movie cuts to a concert hall in Paris. Nazi officers take up the front rows and dot the balcony; a beautiful mystery woman lingers at a doorway. The crown wants Django, but he’s standing by the Seine, drunk, fishing for catfish. An assistant finds him, packs him in the car, and the insouciant Reinhardt greets his aged mom, his band, and others backstage before changing and going on stage.

The music of Reinhardt is recreated for this movie with a group led by Stochelo Rosenberg on lead guitar and augmented by Warren Ellis, longtime sideman of Nick Cave, on violin. It’s a very aggressive, modern simulation, with drums loud in the mix and Rosenberg revving up the speed of the solos to the extent that you might be led to think Reinhardt invented “shred” guitar. It wasn’t to my taste—there’s quite a bit of actual Reinhardt out there to listen to, and these interpretations add nothing I enjoy to the music.

But this isn’t a movie about enjoyment, really. It’s more about Reinhardt’s reluctant heroism as he’s goaded by his manager to undertake a tour of Germany. There, he’ll perform for both Nazis and French workers being held in that country. Django isn’t keen on the idea, and he’s less keen once he’s instructed on how he’ll have to tone down his music for the performances. On the other hand, he could cut a few sides for Deutsche Grammophon! Throughout the movie, Reinhardt, played with little distinction by Reda Kateb, seems less motivated by principle than irritation at being inconvenienced. With the persuasion of the aforementioned mystery woman (Cécile de France), he moves his wife and mom to a town near the Swiss border, where he settles in waiting for passage to the neutral country. In the meantime, he tries to keep a low profile, reuniting with his fellow gypsies. Eventually he’s compelled to play at a Nazi soiree, where—and this is when the movie flirts most blatantly with ridiculousness—the enchantment of his brand of swing music will distract the bad guys sufficiently that a couple of resistance fighters can boat across Lake Geneva, a route usually verboten by circumstances. The end of this movie reminds the viewer of the gypsies who were victimized by Nazis in this period. That’s commendable, but it doesn’t really make up for the fact that “Django” is for the most part everything Reinhardt’s music was not: listless, glum and meandering.