Jane (Libe Barer) can’t stop saying “I’m sorry.” She apologizes to her friends, to her parents, to her sister, to her teachers. She apologizes for existing. Why she does this isn’t immediately apparent in the opening strains of Anna Baumgarten’s “Disfluency,” but the content warning at the start of the film gives us an inkling. “This film contains content that may be difficult for viewers with PTSD. Viewer discretion is advised.” It’s instructive, inasmuch as the film itself wants to be; it’s an unabashed treatise on the way trauma interrupts our lives, short-circuits our esteem, and forces us to take a breath and start over. Oftentimes, that didacticism gets in the way of the picture’s aims, with clunky metaphors and treacly microbudget indie quirks. But a couple of scenes, and some strong performances, make it ultimately worth the sit.

Disfluency, you see, describes the natural interruptions in our normal flow of speech. The uhs and umms and likes and totallys. A teacher helpfully explains this to us in the opening minutes, a particularly creaky delivery system for the messages Baumgarten wants to impart. “Speech is not perfect. Because we are not perfect.” Jane is certainly not, and that disfluency has interrupted her life as well; she’s recently returned home after washing out of her final semester of college for undisclosed reasons. Her mother is disappointed, her father is supportive but ill-prepared, and her sister Lacey (Libe’s real-life sister Ariela, of “How to Blow Up a Pipeline” fame; the pair, naturally, have incredible chemistry) is both worried about and annoyed by Jane’s sudden withdrawnness.

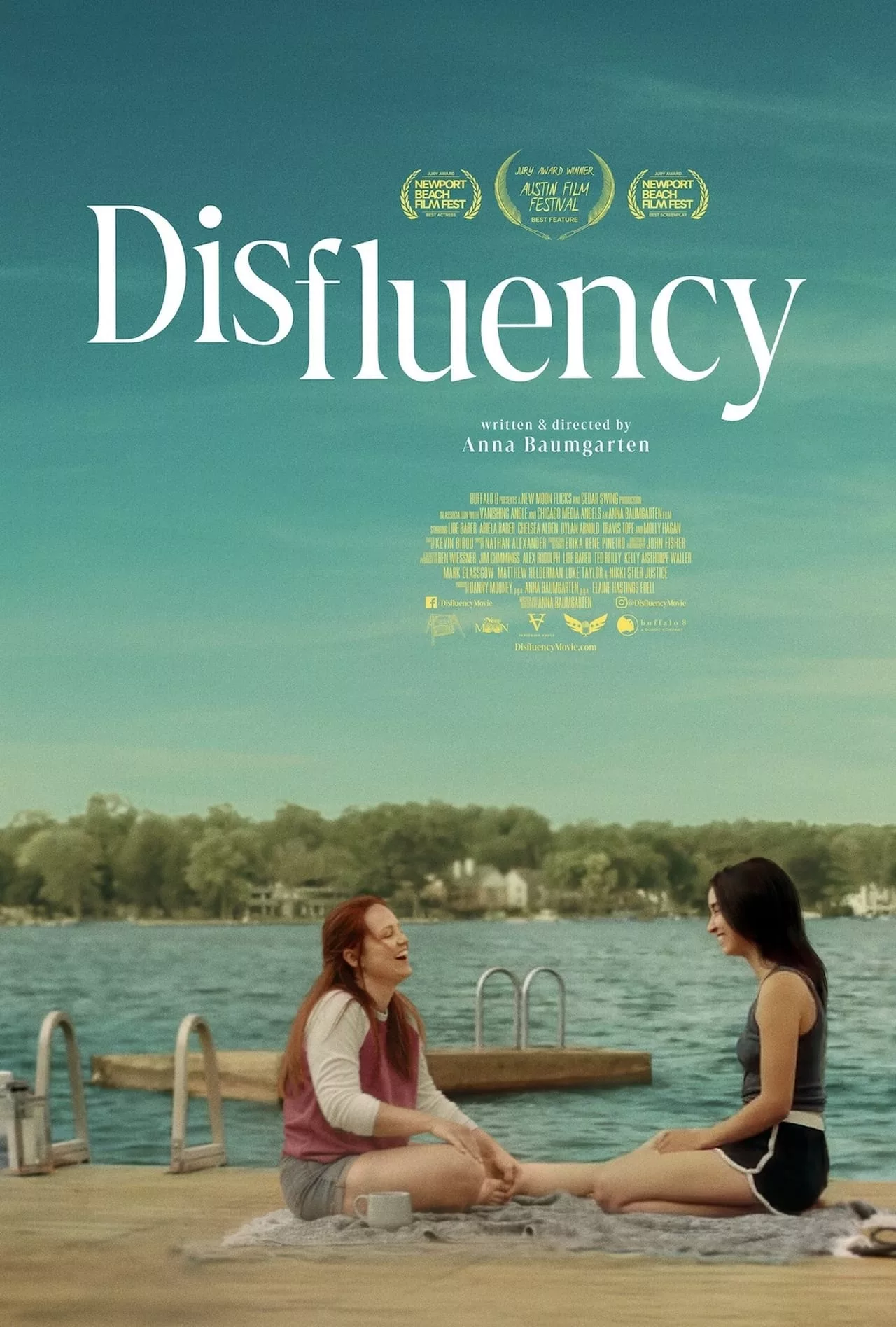

Now, Jane must figure out her next steps, taking a breather with her family in southeast Michigan (where Baumgarten hails, and where this movie was shot) as she figures out what to do about life, her studies as a speech therapist, and the unspoken event she experienced. In the meantime, she whiles away her days with her old high school friends, including Jordan (Dylan Arnold), an old crush who might just be ready to reciprocate that interest. But she also reconnects with old friend Amber (Chelsea Alden), who finds herself suddenly thrust into her own disfluency with the prospect of young single motherhood. Jane quickly notices that Amber’s child is likely Deaf and offers to teach her American Sign Language so they can communicate. But that journey finally gives Jane the vocabulary to speak the truth of what happened to her and catapults her into the messy, imperfect journey of healing and moving forward.

“Disfluency” is adapted from a 2018 short written by Baumgarten and directed by Laura Holliday, and it often suffers from that lengthening. There are two wolves battling for supremacy inside Baumgarten’s script: The warm, family-oriented indie dramedy full of quirky twentysomethings who say things like “I’m exclusively on the ‘Gram now,” and the more sincere, straight-faced exploration of trauma and sexual assault the film blossoms into as it, and Janey, open up about what they’ve gone through. It can be frustrating to feel the script, and Baumgarten’s direction, caterwaul between these two modes, which often feel incongruous—it can be jarring to feel “Lady Bird” turn into “Never Rarely Sometimes Always” and back again.

However, the issues at hand, and the way Baumgarten eventually handles them, elevate “Disfluency” beyond the twee quirkiness of its early stretches. Jane’s trauma makes her discombobulated; she can’t relate to her former peers in ways that move beyond the typical growing apart that comes with distance and time. The fateful night that has come to define her life haunts her, as she dissociates and loses time with the slightest trigger. (Christmas tree lights, like those at the party where the incident occurred, flash in subtly when she remembers, an elegant touch on Baumgarten’s part.) It’s only through the unconditional support of her friends, particularly Amber, and her sister, that she begins to finally confront what happened.

It’s here that “Disfluency” finally picks up steam, as Jane starts to unpack the haziness and uncertainty of a college-party incident whose consensual nature she heavily questions. Barer’s a beautifully brittle nerve here, effortlessly capturing that anxiety that comes from not just facing the trauma of what’s happened to you, but questioning whether it even happened the way you remember. Facing that pain is a heavy burden, especially when others, from supportive siblings to disaffected police officers jotting down handwritten statements, can’t possibly understand what you went through. “Why did I have to think something bad happened to me?!” she wails to Lacey in a police-station bathroom, in the film’s most affecting monologue.

It’s a testament to “Disfluency”‘s ultimate affect, and the lead performances, that it can successfully overcome the preachiness of Baumgarten’s script. The after-school special nature of it, largely contained in the bookending scenes, feel like flagging moments of insecurity, when the film didn’t necessarily need to tie its thorny themes up in a nice, concise bow. Healing, after all, is a messy, perpetually incomplete process. It’s full of disfluency, whether we need a novel new term for it or not. When Baumgarten and her game cast remember that, “Disfluency” hums with surprising resonance.