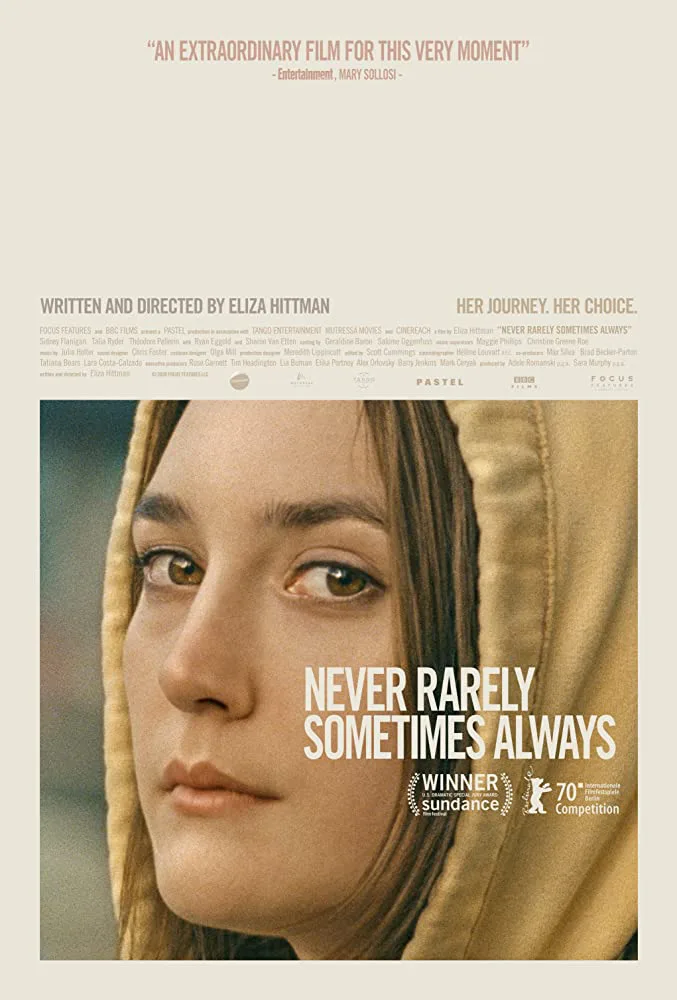

A quiet teenager named Autumn (newcomer Sidney Flanigan) looks like she carries the weight of the world on her shoulders. She’s introduced singing her heart out at a talent show—after her classmates have all either lip synced or done dance routines. There’s something melancholy in Autumn that’s not in most of her peers, and her only friend seems to be her cousin and co-worker Skylar (Talia Ryder). It’s not long before we learn what’s weighing on Autumn’s mind—she’s 17 and pregnant. Eliza Hittman, the writer/director of “Beach Rats,” returns to Sundance with her best work yet, a powerful drama that’s mostly a character study of two fully-realized young women but also a commentary on how dangerous it is to be a teenage girl in America. With stunning performances from two completely genuine young leads, this is a movie people will talk about all year.

Just the simple plot description of “Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Always” makes it sound pretty manipulative: a pair of teenage girls struggle in New York City after one of them becomes pregnant and they have to travel there for an abortion. I’ll admit that I have a very low tolerance for stories of young people or children in jeopardy because it so often feels like a cheap trick to pull at the viewer’s heartstrings. Hittman doesn’t make that kind of movie. Her filmmaking values detail over melodrama, unsparing of the plight of the teenage girl in America, a place that often treats them as objects or preys on them. Whether it’s the bro who makes lewd gestures at a restaurant, the grocery store manager who kisses his female employees’ hands, or the drunk pervert who pulls out his dick on a subway train, teenage girls navigate a minefield of toxic masculinity on a daily basis.

After Autumn learns that Pennsylvania, her home state, requires parental consent, she convinces Skylar to travel with her to New York to get the procedure. With very little money, they make the journey via bus, and are pushed through a system that Autumn wasn’t expecting. What really elevates Hittman’s work here is the sense that Autumn and Skylar are making believable, character-driven decisions on the fly. Whether it’s Autumn piercing her nose after finding out she’s pregnant—maybe to take a form of control again—or how the women scramble to get what they need in New York, decisions feel organic and in-the-moment, adding to an incredible realism that’s embedded throughout the film. It also helps that Hittman is daringly unafraid of silence. There are no monologues. Autumn barely talks at all for long stretches. But Hittman also pushes her camera in close on Flanigan and Ryder, looking for the truth in their faces instead of manipulative dialogue.

Hittman also dodges the “scary city” story that her film could have become. For the most part, the people Autumn and Skylar meet in New York are helpful, especially those in the healthcare system. One in particular asks Autumn a series of questions—the scene which gives the film its fantastic title—and it’s a breathtaking sequence, one in which it feels like Autumn herself is forced to come to terms with things she’s buried, even if just for a few minutes. Flanigan is remarkable in this scene, and throughout the film, and she’s well-matched by Ryder. Lesser writers would have made these two characters too similar, but Hittman trusts Ryder and Flanigan to carve out their own roles. They give two of the best young performances in a very long time.

There are a few minor beats in “Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Always” that feel either too long or too rushed. It’s mostly a pacing issue in the center of the film, but this is a minor complaint for a major, personal work. Hittman’s visual acuity doesn’t draw attention to itself, but don’t underestimate that aspect either, reflected in simple beats like how she captures a Pennsylvania sunrise on a life-changing day or a tired head against a bus window.

There’s an artistry to the filmmaking here that elevates what really matters—her character work. It’s so hard to make stories of young people that don’t feel like they’re using the precariousness of youth as a cheap trick. Adults often write dialogue for teenagers that sounds like posturing—what old people think young people sound like—or they embed moral messages in barely-remembered memories of their younger days. The reason that “Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Always” is such an impressive piece of work is that Hittman has such deep compassion for her two leads, a pair of young women pushing through a world that is constantly putting obstacles in their path. You won’t forget them.

This review was filed from the 2020 Sundance Film Festival on January 25th, 2020 and is being re-run now that it is on VOD, 4/3.