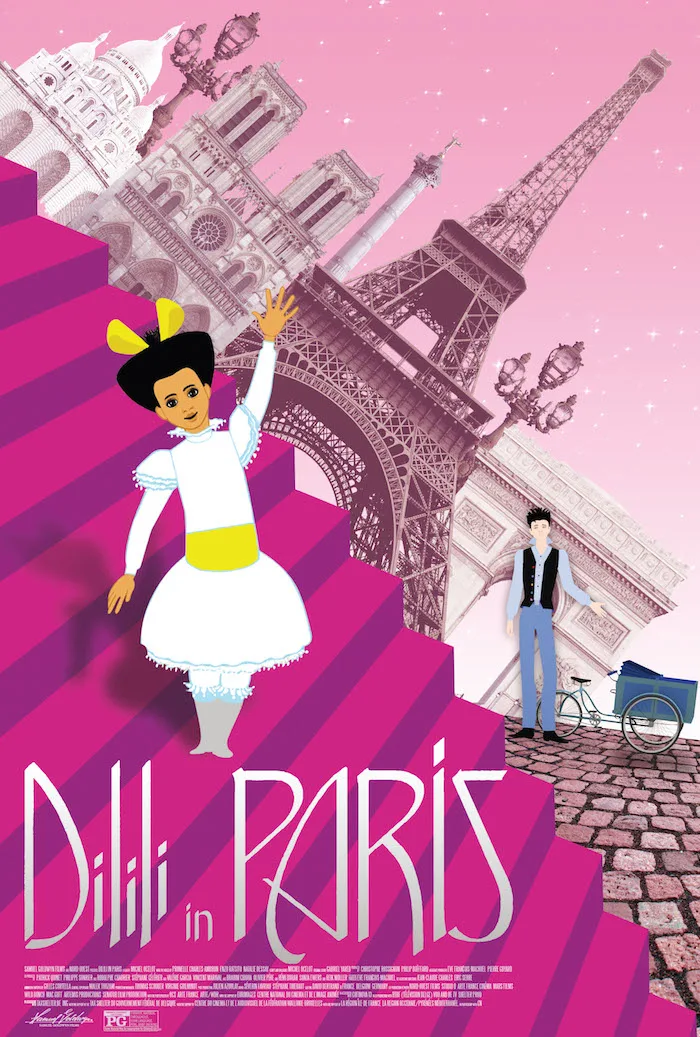

If films were judged purely on the basis of their good intentions, then French writer/director Michel Ocelot’s animated adventure, “Dilili in Paris,” would easily earn four stars. When it comes to role models for children, this picture’s titular, pint-size heroine is as good as it gets, embodying the very essence of pluck and resilience. Born into the indigenous Melanesian culture known as “Kanak” in New Caledonia, Dilili sneaks onto a boat bound for France, where she is taken under the wing of a countess. Having already been taught the dominant Parisian language by noted educator and anarchist Louise Michel, Dilili’s eloquence outclasses that of all commoners once she arrives in Europe. Equipped with an insatiable curiosity and no detectable trace of homesickness, the girl is eager to join Orel, a new friend twice her height, on a picturesque journey through Paris, as they go about solving the mystery of a misogynistic cult known as the Male Masters. All Dilili has to do is curtsy while uttering her maddening catchphrase, “I am pleeeeased … to make your acquaintance,” in order to win over and enlist the aid of every feminist icon who crosses her path.

Winner of the Cesar Award for Best Animated Feature, Ocelot’s film would seem poised to emerge as a surefire Oscar contender, especially considering the mediocrity of this year’s recycled offerings from Disney. Alas, on the eve of its U.S. release, “Dilili in Paris” was screened for critics in an English dub, and it is a complete disaster. Though Roger Ebert worried that little ones wouldn’t know what to make of the subtitles in Ocelot’s 2012 anthology film, “Tales of the Night,” I’m willing to bet that the ability of kids’ eyes to multitask when glancing at text and images sharing the same screen has increased exponentially in the era of iPhones. I saw my first subtitled film at age 12, and quickly forgot that I was reading each line, as I became fully immersed in the emotions conjured by both the visuals and the actors’ voices. 12 would also be the recommended age for this movie, which is bound to frighten or confound younger viewers with its mature themes and top-heavy exposition.

The film’s opening moments are promising enough, in part because it’s the only nonmusical sequence preserved in its native tongue, as we see Dilili in what appears to be New Caledonia. Suddenly, she finds herself being scrutinized by the eyes of a white stranger. Then the shot pulls back to reveal that we are, in fact, already in Paris, where Dilili has been put on display in a recreation of her former Kanak village. Dilili is acutely aware of how her dark skin causes numerous local folk to look down on her in judgement, yet her relentlessly perky voice-over shields itself from any semblance of vulnerability or nuance. So focused are the English actors in mimicking the rhythm of the original French dialogue and movements of the animation that it frequently causes the characters to pause in random places, as if they were all possessed by the awkward cadences of Christopher Walken. Some of the translations are so wordy that they verge on self-parody, such as when the Prince of Wales inadvertently magnifies the absurdity of a key set-piece by saying, “Young man, let me congratulate you on your swiftness and your ability to unharness a horse without unnecessary movements and in complete silence!” Even the simple act of whispering is botched, with Dilili delivering the most pronounced background murmur since Mel Brooks hollered, “Harrumph Harrumph!” in “Blazing Saddles.”

Perhaps this wouldn’t have been as glaring a demerit if the plot were more engaging. There’s no shortage of fascinating historical figures on display here, yet the film is only as interested in its Belle Époque period setting as “The Pagemaster” was in books. All the trailblazing artists, scientists, engineers and revolutionaries rounded up here are used merely as set dressing for a dull caper that turns ludicrous in the final act, with easily identifiable foes occupying the sort of lair typically reserved for Bond villains. We’re granted fleeting informational soundbites such as “Monet is about color, while Renoir is about happiness,” before Dilili quickly changes the subject to the fictional Male Masters, whose dehumanizing treatment of women held captive in their subterranean underworld registers as a heavy-handed metaphor for female oppression. It trivializes the #MeToo movement just as “The Day After Tomorrow” turned the urgent threat of climate change into a monster no more credible than Godzilla. Most egregious of all is the character of Lebeuf, who refers to Dilili as an ape before undergoing an abrupt change of heart, leading him to admit that he was an “idiot,” though “racist” would’ve been a more appropriate word choice. The fact Orel nevertheless trusts that Dilili will be safe in Lebeuf’s custody is one of many instances where the film stretches our suspension of disbelief past its breaking point. I was especially amused by the moment when a crowd of parents wait patiently to embrace their rescued offspring just so an opera singer can finish her solo.

Many of the film’s backdrops are admittedly breathtaking, yet the foregrounded people never seem to be actually populating them. The character animation is so flat and uninspired that it causes Dilili and her fellow humans to resemble stickers grafted onto postcards, with the subtle use of shadows and reflections doing little to add dimension. What made 1998’s “The Prince of Egypt” the gold standard for this sort of visual approach is the painterly texture that was given to its computerized landscapes, allowing them to blend more seamlessly with its hand-drawn characters. Nothing about “Dilili in Paris” feels natural or organic, a fact only intensified by such clunky exchanges as this one between Dilili and Colette, a performer of Egyptian pantomime and future author of Gigi…

Colette: “I show my body a little bit during the dance…because it’s beautiful!”

Dilili: “It is very nice of you.”

Colette: “It is an interesting activity.”

If only Colette were around today to pen a rewrite.