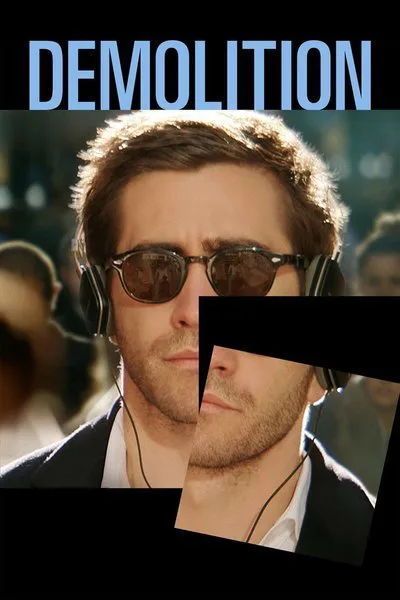

“Go through hell and look cool doing it.” That’s the vibe I got from the poster for “Demolition,” which uses a neatly quartered (with one segment slightly askew) portrait of its male lead, Jake Gyllenhaal, sporting expensive shades and wearing expensive headphones. Is that an overly simplistic reading of the actual film? Yes. But it’s also true that the movie, costarring Naomi Watts and directed by Jean-Marc Vallée, doesn’t exactly shy away from those semiotics.

“Demolition” opens with Gyllenhaal’s Davis Mitchell and wife Julia (Heather Lind) driving around New York City and having what seems to be a tetchy power-couple morning. He’s preoccupied, she’s frustrated, and they’re on a phone call with her parents. The viewer can’t get a read on the marriage: it’s strained is a good guess, but whether it’s truly crummy or just circumstantially challenged is impossible to tell. Speculation becomes moot when an auto accident leaves Julia dead and Davis without a scratch.

Davis is zombied out. He can’t get an M&Ms bag from the hospital’s vending machine, and he writes an uncharacteristically confessional letter to the vending machine’s parent company. He can’t cry at his wife’s funeral. His father-in-law Phil (Chris Cooper), who’s also his boss at a financial shark tank, advises him to take apart his life and reexamine it. Davis, who’s also found that he can no longer lie effectively, takes this counsel literally, and begins to physically dismantle various appliances. And he continues pouring what’s left of his heart out to vending machine customer service, whose human form is that of Naomi Watts.

If Davis’ prior life was a cold slate-grey corporate mess, the life of Watts’ Karen is a lukewarm, pot-haze suffused suburban one, complete with a teen son (Judah Lewis) who’s a handful of rock and roll attitude. You can tell the extent to which this whole movie’s narrative and its attendant lessons are big time bits of boomer wish fulfillment contrivance by the fact that it offers up, in this day and age, a fifteen-year-old who’s obsessively into Eric Burdon, David Bowie, and vintage Free. The kid, of course, becomes an eager accomplice as Davis, looking for answers, takes down his entire house. In which he does, indeed, discover an important clue.

The yuppie-finding-his-soul scenario is a very old and not particularly compelling one, and the fact that this film borrows elements from “Regarding Henry,” “American Beauty,” Saul Bellow’s “Herzog,” and the Jim Carrey “Liar, Liar,” for heaven’s sake, does not exactly redound to its benefit.

However, Vallée directs with no small amount of verve and energy, as if he genuinely believes he can bring something new to this particular table. The actors show similar commitment, with Gyllenhaal conveying inner emptiness and/or confusion in a smartly understated way. While Watts is reliably vulnerable, it’s Judah Lewis as her son Chris who does the heavier emotional lifting. The scenario does contain a couple of unexpected stings in its tale, which almost makes the inevitable redemption payoff play a little less pat than it might have under different circumstances. But not THAT much less pat.