This is another of Roger Ebert’s final reviews, which we were holding until the movie opened theatrically. We published the very last one he wrote, of Terrence Malick‘s “To the Wonder,” last week.

There is this. The conjurer Ricky Jay is in London appearing in a documentary for the BBC. A journalist for the Guardian is sent to interview him over lunch. Driving to the restaurant, they lose their way, arrive an hour late, and are given the only available table.

The doc is about Jay and the legendary figures who have inspired him since he became, at 15, the youngest magician to ever appear on TV. So he says. You always add “so he says.” He’d spoken of many things, including a 19th-century trick that has defied all explanation. She asked him for more detail. It involved a magician producing coins from under a hat on his table, and then something else.

They had just been seated at the empty table. Ricky Jay propped his menu on the table in front of him. At the end of his story, he raised the menu and revealed a foot-square block of ice, already melting into a puddle. That sounds impossible, but it’s what the interviewer says she saw.

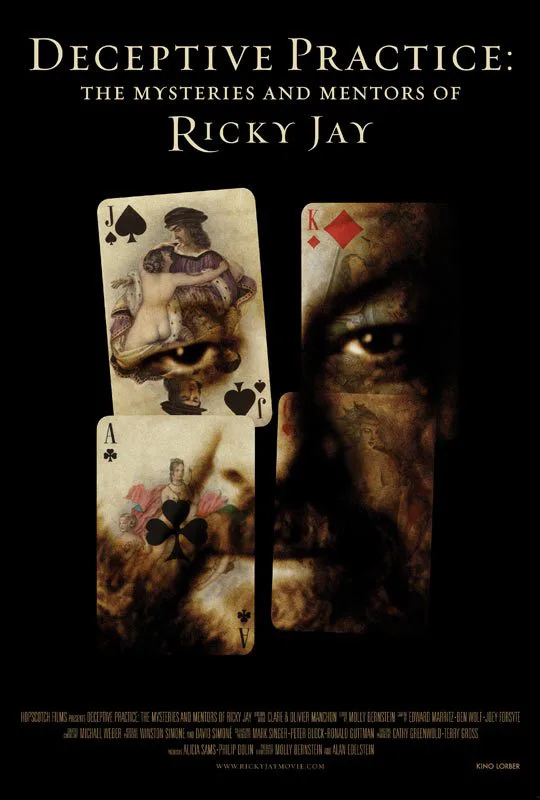

Well? It’s a trick, right? I agree. I don’t believe in magic. But how was it possibly performed? “Deceptive Practice: The Mysteries and Mentors of Ricky Jay” is a documentary about the famed magician, card manipulator and actor and the people he has learned from in life and history, including the Great Slydini and a bright 15-year-old who is his current protégé.

I first became aware of Jay in David Mamet‘s directorial debut, “House of Games” (1987), where he played a man sitting in on a poker game. Jay effortlessly stole the scene from the others. This was a man who knew something. He had additional information. He saw through you. Even in a labyrinthine puzzle thriller, he knew the way through. He didn’t go for effect. He was amused at your assumptions.

This film is a doc about the young man’s devilment. He seems perfectly happy — ecstatic, even — seated at a table in front of a three-sided mirror and practicing card moves over and over and over again. As a kid, he learned moves from his grandfather. He moved away from home in his early teens.

There’s a film of his stage show, “Ricky Jay and his 52 Assistants,” devoted largely to his career and his collection of countless books, posters, programs, photographs, props and memories from magicians. It’s of interest primarily to people who like that kind of stuff. I do, up to a point. What I find even more fascinating is Jay’s ability to lose himself in it.

He always holds a card you don’t see. After his show in Chicago I went backstage and said how happy I was to meet him.

“Oh, this isn’t the first time we’ve met,” he informed me. “We met at the University of Illinois. You ran a piece by me in that little magazine you started.”

He named it. He had the title correct. Even I had forgotten it.

“Of course,” he said, “I didn’t sign it with this name.”

“How did you sign it?”

“That you will never know.”

Nor will I. Or whether he really did. Or whether he attended Illinois, which is not listed in any of his biographical material. And the block of ice is nearly melted by now.