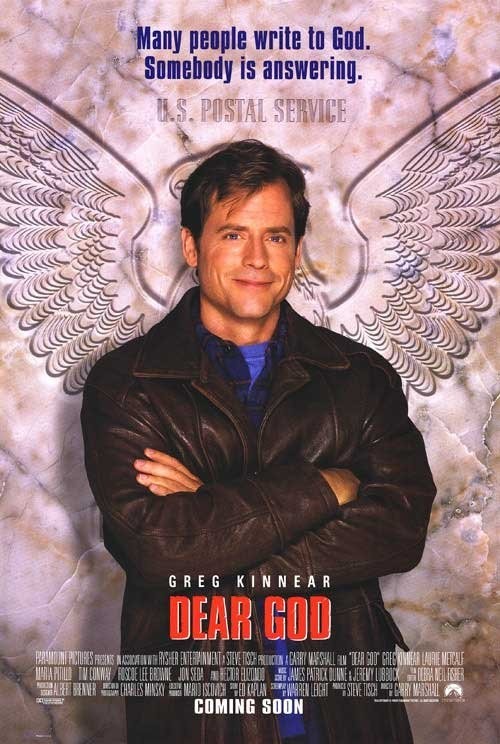

“Dear God” is the kind of movie where you walk out repeating the title, but not with a smile. It is a limp, lifeless story starring Greg Kinnear as a con man who becomes a do-gooder, and one of its many problems is that he was a lot more entertaining as a con man.

As the movie opens, Kinnear has his arm wrapped in bandages and is hanging out near ATM machines, pretending to be a burn victim in need of a loan. He has other scams, like returning a “lost” bracelet to get a reward, and selling bogus airline tickets. That last one gets him arrested by the LAPD and brought up before a judge who sentences him, horror of horrors, to get a real job.

Kinnear eventually ends up working for the post office, where there’s time to brief him on only a few of the rules (“Fragile” is postal for “bounce against walls”) before he’s assigned to the dreaded Dead Letter Office, where demoralized clerks try to deal with mail addressed to Elvis, the Tooth Fairy and God.

By now we are slipping inexorably into the realm of cut-rate Capra, and can guess what’s coming: Kinnear will read some of the letters, be moved by the plight of the writers, and try to change their lives a little. And he will enlist the aid of some of his co-workers, including Laurie Metcalf as a former lawyer, Roscoe Lee Browne as a worker on the verge of retirement, Tim Conway as a former carrier so morose over losing his route that he seems on the verge of going postal, and Hector Elizondo as the supervisor, a Russian immigrant with his own weird approach to things.

Director Garry Marshall, who usually makes sharper and smarter films, lays on schmaltz by the carload as Kinnear and his friends save a man from committing suicide, do a maid’s own housework for her and give a harassed mother of twins her heart’s desire: just one evening off.

Greg Kinnear, it must be said, holds his own in the film. If it’s boring, that’s not his fault. The onetime TV talk show host proved, in the remake of “Sabrina,” that he is a sure-enough actor, and here again he has an easy, engaging quality. But the material lets him down with its relentlessly predictable developments.

The good deeds quickly become a media phenomenon. “The Postal Miracles” become so famous that Los Angeles TV stations interrupt their scheduled broadcasts for bulletins from the site of the latest good deed (uh, huh). Everything eventually ends up in court, where Kinnear and his angelic accomplices are charged with “answering God’s mail without authorization.” The courtroom scene, I am coming to believe, is the last refuge of the screenwriter who needs an ending and does not have one.

There is a new book out titled “Reel Justice,” which examines many famous movies on the basis of how accurate their legal scenes are. I commend “Dear God” to them, as an example of the same fallacy committed by “A Time to Kill.” This is the verdict brought in according to the requirements of the plot, rather than the rules of the law. If a defendant breaks the law, and admits he did it, and it is generally agreed that he did it, then he cannot be found “not guilty.” He can be given a light sentence, a tap on the wrist, or fined $1.

But the law in non-Kafkaesque nations cannot simply ignore the facts. Not that I cared. It was more like by that point in the film I needed something–anything–to think about.