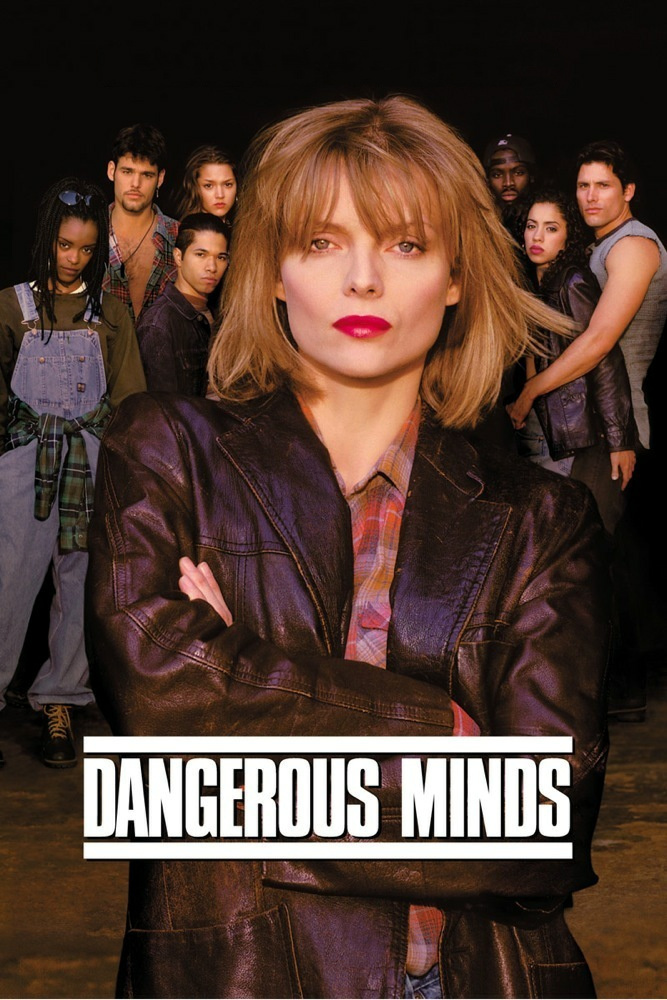

“Dangerous Minds” tells another one of those uplifting parables in which the dedicated teacher takes on a schoolroom full of rebellious malcontents, and wins them over with an unorthodox approach. Movies like this are inevitably “based on a real story.” Maybe they tell you that because otherwise you’d think they were pure fantasy.

The movie stars Michelle Pfeiffer as LouAnne Johnson, an ex-Marine who applies for a teaching job and is hired on the spot, to teach in “sort of a school within a school,” she’s told, “made up of special kids – passionate, challenging.” A fellow teacher (George Dzundza) is more forthright: “These are bright kids, with little or no educational skills, and what we politely refer to as social problems.” Johnson soon provides a third opinion: “Rebels from hell.” She enters the classroom and is immediately hooted down by a scornful class of African-American and Hispanic students who call her “white bread.” She returns the next day with a more forthright approach: “I am a U.S. Marine. Anybody know any karate?” They do, but mostly from kung-fu movies, and after she has thrown a couple of the kids, she gets their attention.

Her teaching methods are inventive. She bribes them with candy bars and free trips to amusement parks, and involves them in the words of that important poet, Bob Dylan (the Tambourine Man might have been a drug dealer!). Soon they’re in the school library, finding connections between Bob Dylan and Dylan Thomas. (First prize: dinner with the teacher in the nicest restaurant in Palo Alto.) We have seen this basic story before, in “Stand and Deliver,” “Lean On Me,” “Teachers,” “Dead Poets Society,” and so on.

This version is less than compelling. There is Emilio, the obligatory rebellious class leader (Wade Dominguez), and Raul, the class brain (Renoly Santiago), and Callie (Bruklin Harris), the bright girl who gets pregnant and is headed for “unwed mothers classes” when Johnson discovers she can stay in school if she wants to.

Pfeiffer, who is a good actor, does with this material what she can, and there is a nice scene where she tells Raul’s parents they can be proud of their son. But examine the assumptions here.

What, exactly, will these disadvantaged inner-city kids accomplish by being bribed with candy bars and the “relevancy” of Bob Dylan? Can they read and write? Can they compete in the job market? An educational system that has brought them to the point we observe in the first classroom scene has already failed them so miserably that all of Miss Johnson’s karate lessons are not going to be much help.

Wondering about the Dylan-Dylan connection, I went looking on the Internet for more information about My Posse Don’t Do Homework, the 1992 book by LouAnne Johnson that inspired this movie.

I found out something interesting: The real Miss Johnson used not Dylan but the lyrics of rap songs to get the class interested in poetry.

Rap has a bad reputation in white circles, where many people believe it consists of obscene and violent anti-white and anti-female guttural. Some of it does. Most does not. Most white listeners don’t care; they hear black voices in a litany of discontent, and tune out.

Yet rap plays the same role today as Bob Dylan did in 1960, giving voice to the hopes and angers of a generation, and a lot of rap is powerful writing.

What has happened in the book-to-movie transition of LouAnne Johnson’s book is revealing. The movie pretends to show poor black kids being bribed into literacy by Dylan and candy bars, but actually it is the crossover white audience that is being bribed with mind-candy in the form of safe words by the two Dylans. What are the chances this movie could have been made with Michelle Pfeiffer hooking the kids on the lyrics of Ice Cube or Snoop Doggy Dogg? The answer to that question is in the absence of rap from the movie, and the way the score swells shamelessly when Emilio the rebel finally hears some Dylan he likes, and stirs from his insolent sprawl to say, “read those lines again.” As a graduate student I was on a year’s fellowship at the University of Cape Town, and taught once a week in a night school in a black township. The students were preparing for an examination that might get them into university classes. The syllabus was the same as for white students, and we studied Shakespeare’s The Tempest. There was irony there: young people living under apartheid, in a township where the necessities of life were scarce, after a long day of manual labor, studying Shakespeare so that they, too, could take a test that for white students would be second nature.

And yet . . . at least Shakespeare was worth studying, and his ideas and poetry involved them, and those who stuck it out had accomplished something worth doing. Bob Dylan was more relevant in Cape Town in 1965 than in Palo Alto in 1995, but even then, taking up their time with him would have been a con game.