“Crown Heights” is a pretty good movie about a great subject: the sheer backbreaking labor necessary to force the system to even acknowledge a terrible injustice, much less make it right. Written and directed by Matt Ruskin, the film retells the story of Colin Warner (“Short Term 12” star Lakeith Stanfield), a Brooklyn man from a Trinidadian family whose life as a burglar and car thief was interrupted by a 20-year stint in prison for a crime that nobody, including the officers who arrested him, thinks he committed.

The story begins on April 10, 1980, when Colin Warner is arrested in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn. He thinks he’s been busted for stealing a car. The cops inform him that he’s being charged with shooting and killing a local Jamaican teenager named Mark Hamilton in the nearby neighborhood of Flatbush. Colin tells him he’s innocent. It’s not that they don’t believe him; they just don’t care. Somebody has to go to jail for the crime, and it’s going to be Colin. He’s on the hook because he has a criminal record and a witness was coerced into picking his photo out of a book of mugshots. The witness, a frightened young teenager (Skylan Brooks), recants his testimony on the stand, but it doesn’t matter. Turner is sentenced to 15 years to life, with a possibility of early release if he expresses remorse for a crime he did not commit.

Up until this point, Ruskin’s film is compelling but unremarkable. Its wobbly blue-grey images are shot close and cut fast, the default visual language of TV programs about urban cops and robbers. The storytelling is similarly rushed, sprinting through moments that might’ve been profoundly wrenching if the movie had enough faith to stay inside a moment. (Give the director credit, though, for having the old-movie gumption to jump ahead several years in a single cut and trust Stanfield’s performance to fill in the emotional connective tissue.)

The visual storytelling never develops much personality, but the screenplay’s decision to shift focus from Warner to his best friend Carl (former Oakland Raider Nnamdi Asomugha) energizes and focuses the story. As Carl goes from house to apartment to government office, re-investigating the case, debating and chastising lawyers, and ultimately crowdfunding neighborhood money to hire William Robedee (Bill Camp), an attorney who seems as outraged by Colin’s plight as Carl is, “Crown Heights” sketches the entwined obstacles standing between the hero and his freedom: racism and institutional exhaustion.

This is a world in which poor people’s lives, more so black and brown lives, don’t matter to the state. Colin and the man who actually committed the murder are considered interchangeable as long as the case can be marked “solved” and the overworked, cynical employees of the police department, the prison system and the courts can get a green light to move along to the next outrage, which will likely also be dispatched in a cursory way. There’s a long section in the middle of “Crown Heights” where Colin and Carl’s stories play off each other in a grandly melodramatic and satisfying way, echoing sections of HBO’s recent potboiler “The Night Of,” which had a similar color palette. The film alternates between Colin trapped behind bars, turning into the kind of dead-end hard-case that the arresting officers already insisted he was back in 1980, and Carl, William Robedee and other allies working to exonerate him, uncovering ever-more-appalling proof of the brokenness of the system.

The problem is, despite the best efforts of Ruskin’s writing and direction and Stanfield’s expressive performance (it’s all in the eyes), Colin’s story remains the tale of a martyr to the system, struggling to hold onto shreds of his dignity as he’s stripped, de-loused, caged with an actual murderer, packed into a cell block with gangbangers and assorted creeps, and repeatedly urged to express remorse for the murder, something he refuses to do because he’s innocent. This is a powerful story but also a familiar and essentially passive one. Despite moving scenes of Colin falling in love behind bars with his sweetheart from the outside (Natalie Paul) and belatedly studying the law in an attempt to save himself, the sequences that show Carl battling injustice on the outside are more dynamic and fresh. They also make every point that Colin’s story makes, but in an active way, with a chess aspect: is a legal checkmate possible here, and if so, what moves will get them there?

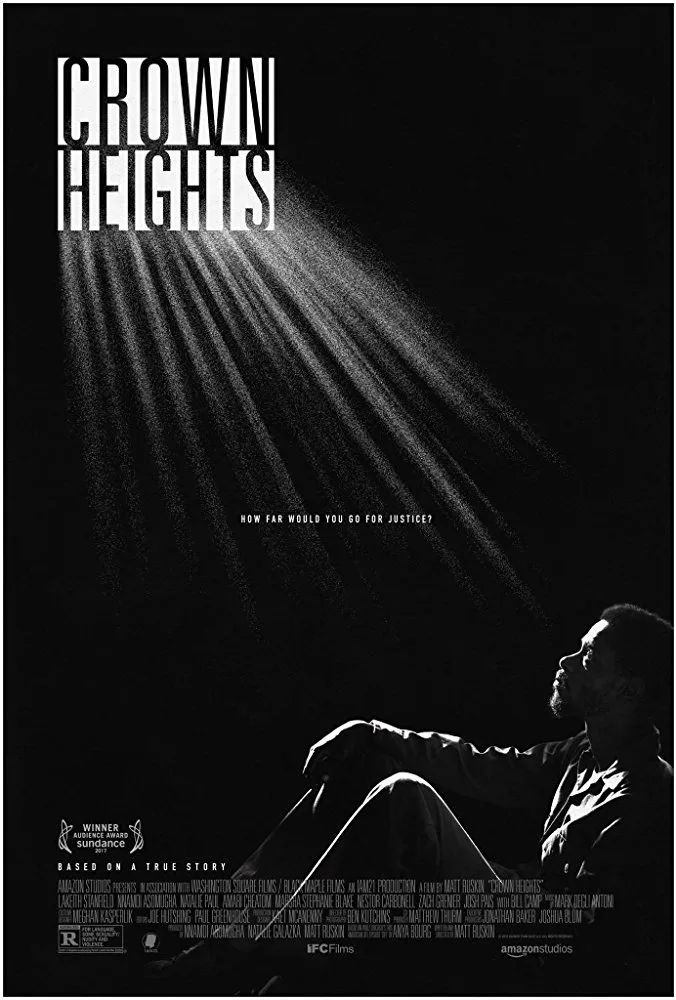

Ruskin’s commitment to giving both men’s stories equal screen time is honorable, but it tends to staunch the momentum of a given storyline whenever it’s threatening to build to a head. The film’s climax is powerful nonetheless, and the performances carry the day. Stanfield is a true movie star, radiating decency even as the character’s shell hardens, and Asomugha, who is credited as a producer, holds his own against some formidable character actors, including Camp, who’s turning into one of the MVP’s of cinema and television. The film’s signature image is of the hero’s eyes, which take in sights that no one should see.