I wonder if they have a squad out in Hollywood named the Movie Police, who swoop down on screenplays and enforce all of the obligatory cliches and story formulas. Every once in a while you find a movie that has the spark of inspired craziness in it, that has a few scenes that tell you the people who made the movie were nutty but brilliant. And then, just when your hopes are beginning to stir – the Movie Police strike.

“Excuse me, sir. Movie Police here. Do you have a love story in this movie?” “Uh, afraid not. There’s no need for one.” “But who is the female lead?” “There isn’t any.” “And the heart-warming romantic conclusion?” “Are you kidding? This is a cynical satire about advertising.” “And do you have a lot of lovable, huggable goofballs in supporting roles?” “Only the usual demented creative types who work in any ad agency.” “Then I’m afraid you’ll have to come down to the studio with us. What you’ve done is against . . . Movie Law!” Why do I get the feeling a scene like this was played at some point early in the history of “Crazy People”? Because the two halves of the movie fit together so uneasily.

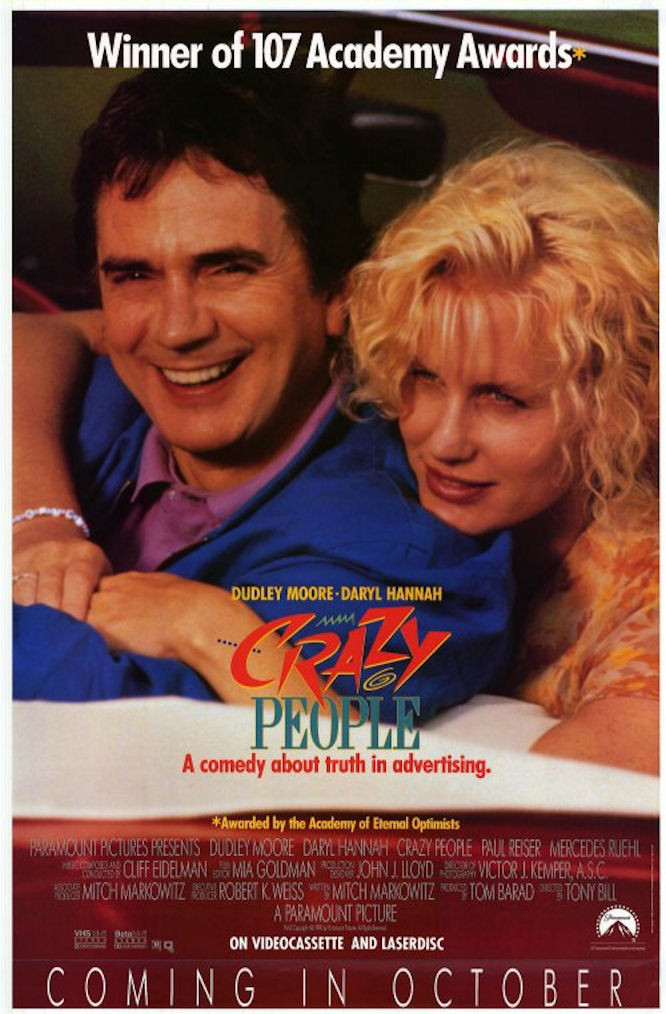

On the one hand, we have Dudley Moore, a demented and crazed advertising genius who gets fed up with the hypocrisy of routine advertising and creates his own campaigns – campaigns that tell the literal, brutal, sacrilegious truth. On the other hand, we have a subplot involving his romance with a sweet girl he meets in an insane asylum, and, yes, there is a crowd of lovable, huggable goofballs who are vindicated in the relentlessly upbeat ending.

Moore plays Emory Leeson, ad man. Most of the unorthodox campaigns he creates for his clients can’t be quoted here, because they deal in very direct sexual imagery. Let it be said, however, that many of the campaigns inspire loud and delighted laughter from the audience.

“Crazy People,” in fact, has more really big laughs in it than any other unsuccessful comedy I’ve seen. What’s especially fun is when the campaigns are printed by mistake, and we see the reactions of a public exposed for the first time to things they have secretly believed for a long time.

The ad campaigns are rude, obscene and hilarious. The rest of the story is sappy, as Moore’s colleagues have him committed to a mental institution. At first he protests that he doesn’t belong there, but then he begins to like the place, to enjoy the competent care of the psychiatrist (Mercedes Ruehl) and the soothing tenderness of a beautiful blond patient (Daryl Hannah). Before long, and without any preparation or particular justification for such a miracle, Moore and Hannah are in love. And Moore doesn’t ever want to leave this wonderful place – especially not if it means returning to the real madhouse of the ad agency.

There is nothing really wrong with the scenes in the institution, except that they’re in the wrong movie. Hannah is warm and engaging as the young woman who loves Moore (I like her better in these everyday roles than when she gets saddled with weirdos), and Ruehl (the mobster’s wife in “Married to the Mob“) avoids all of the usual psychiatrist cliches. The other patients in the institution turn out, inevitably, to be natural-born advertising geniuses, of course. (One of the basic Movie Police Laws is that crazy people are always saner than the rest of us.) My question is: What’s this sweet, sunny story doing in the same movie with all of those cheerfully offensive ads? Why couldn’t the movie have followed its first instincts and been a hard-edged, cynical social satire? A few weeks before this film was released, Michael Caine starred in “A Shock To The System,” a movie that did have the courage of its dark convictions and followed them through to the end. Now there is a movie that has never asked itself this basic question: Why would the kind of people who would laugh at the rude ads in “Crazy People” be interested in its cutesy-poo subplot?