Characters motivated by money are always more interesting than characters motivated by love, because you don’t know what they’ll do next. Tom Wolfe knew that when he wrote The Bonfire of the Vanities, still an accurate satire of the way we live now. Maybe that’s why writers from India, where marriages are often arranged, are the most interesting new novelists in English.

The Victorians knew how important money was. The plots of Dickens and Trollope wallowed in it, and Henry James created exquisite punishments for his naively romantic Americans, caught in the nets of needy Europeans. And now consider “Cousin Bette,” a film based on one of Balzac’s best-known novels, in which France of the mid-19th century is unable to supply a single person who is not motivated more or less exclusively by greed. Wolfe said his Bonfire was inspired by Balzac, and he must have had this novel in mind.

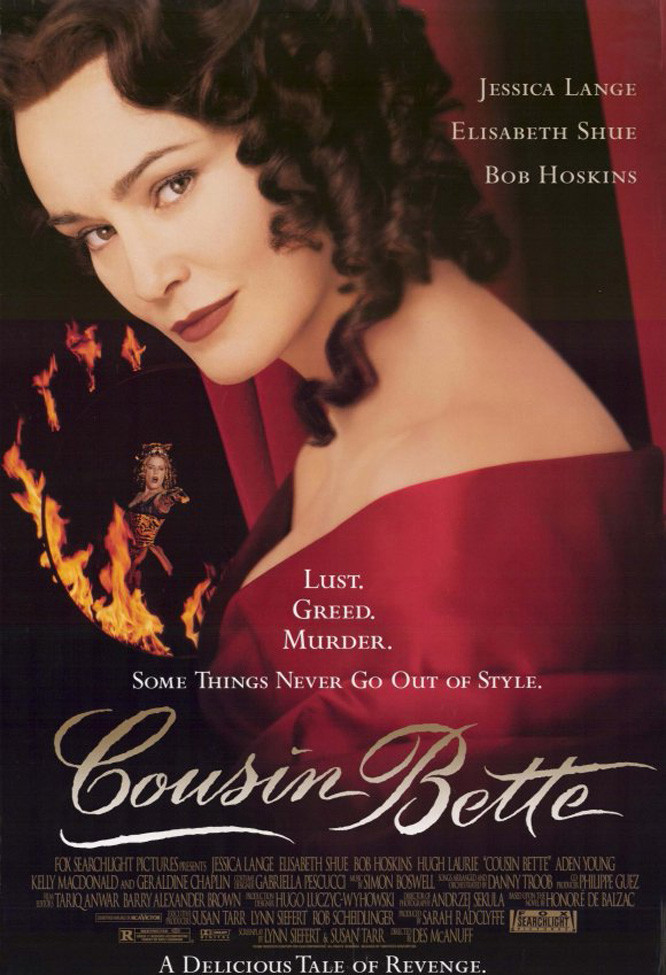

The title character, played by Jessica Lange with the gravity of a governess in Victorian pornography, is a spinster of about 40. Her life was sacrificed, she believes, because her family had sufficient resources to dress, groom and train only one of their girls–her cousin Adelaide (Geraldine Chaplin). Bette was sent to work in the garden, and the lucky cousin, on her death bed, nostalgically recalls the dirt under Bette’s nails. When the cousin dies, Bette fully expects to marry the widower, Baron Hulot (Hugh Laurie). But the baron offers her only a housekeeper’s position.

Refusing the humiliating post, Bette returns to her shabby hotel on one of the jumbled back streets of Paris, circa 1846, where the population consists mostly of desperate prostitutes, starving artists and concierges with arms like hams. Bette is not a woman it is safe to offend. She works as a seamstress in a bawdy theater, where the star is the baron’s mistress, Jenny Cadine (Elisabeth Shue). The rich playboys of Paris queue up every night outside Jenny’s dressing room, their arms filled with gifts. Baron Hulot does not own her, but rents her, and the rent is coming due. Bette knows exactly how Jenny works, and uses her access as a useful weapon (“You will be the ax–and I will be the hand that wields you!”).

Every night, pretending to sleep, Bette watches as Wenceslas (Aden Young), the handsome young Polish artist who lives upstairs, sneaks into her room to steal the cheese from her mousetrap and a swig of wine from his jug. She offers to support him from her savings (as a loan, with interest, of course) and falls in love with him, only to learn that he has fallen in love with Jenny. (“They say,” Jenny unwisely tells Bette, “that he lives with a hag. A fierce-eyed dragon who won’t let him out of her sight.”) Meanwhile, the baron is bankrupt and in hock to the moneylenders. His son fires the family servants in desperation. Nuncigen, a familiar figure from many of Balzac’s novels, lends money at ruinous interest. And the baron’s daughter Hortense (Kelly MacDonald) unexpectedly weds Wenceslas, who unwisely allows love to temporarily blind him to Jenny’s more sophisticated appeals. Also lurking about is the rich lord mayor of Paris, Crevel (Bob Hoskins), who once offered Hortense 200,000 francs for a look at her body, and is now, because of her desperation, offered a 50 percent discount.

All of these people are hypocrites, not least Wenceslas, who designs small metal decorations and poses as a great sculptor. When the baron, now his father-in-law, underwrites the purchase of a huge block of marble, Wenceslas’ greatest gift is describing what he plans to do with it.

This is a plot worthy of “Dynasty,” told by the first-time film director Des McAnuff with an appreciation for Balzac’s droll storytelling; he treats the novel not as great literature but as merciless social satire, and it is perhaps not a coincidence that for his cinematographer he chose Andrzej Sekula (“Pulp Fiction“), achieving a modern look and pace. The movie is not respectful like a literary adaptation, but wicked with gossip and social satire. (“The 19th century as we know it was invented by Balzac,” Oscar Wilde said.) Between 1846, when the movie opens, and 1848, when it reaches a climax, popular unrest breaks out in Paris. Angry proletarians pursue the carriages of the rich down the streets, and mobs tear up cobblestones and build barricades. Balzac’s point is that history has dropped an anvil on his spoiled degenerates. But the plot stays resolutely at the level of avarice, and it is fascinating to watch Cousin Bette as she lies to everyone, pulls the strings of her puppets, and distributes justice and revenge like an angry god. By the end, as she smiles upon an infant and the child gurgles back, the movie has earned the monstrous irony of this image.