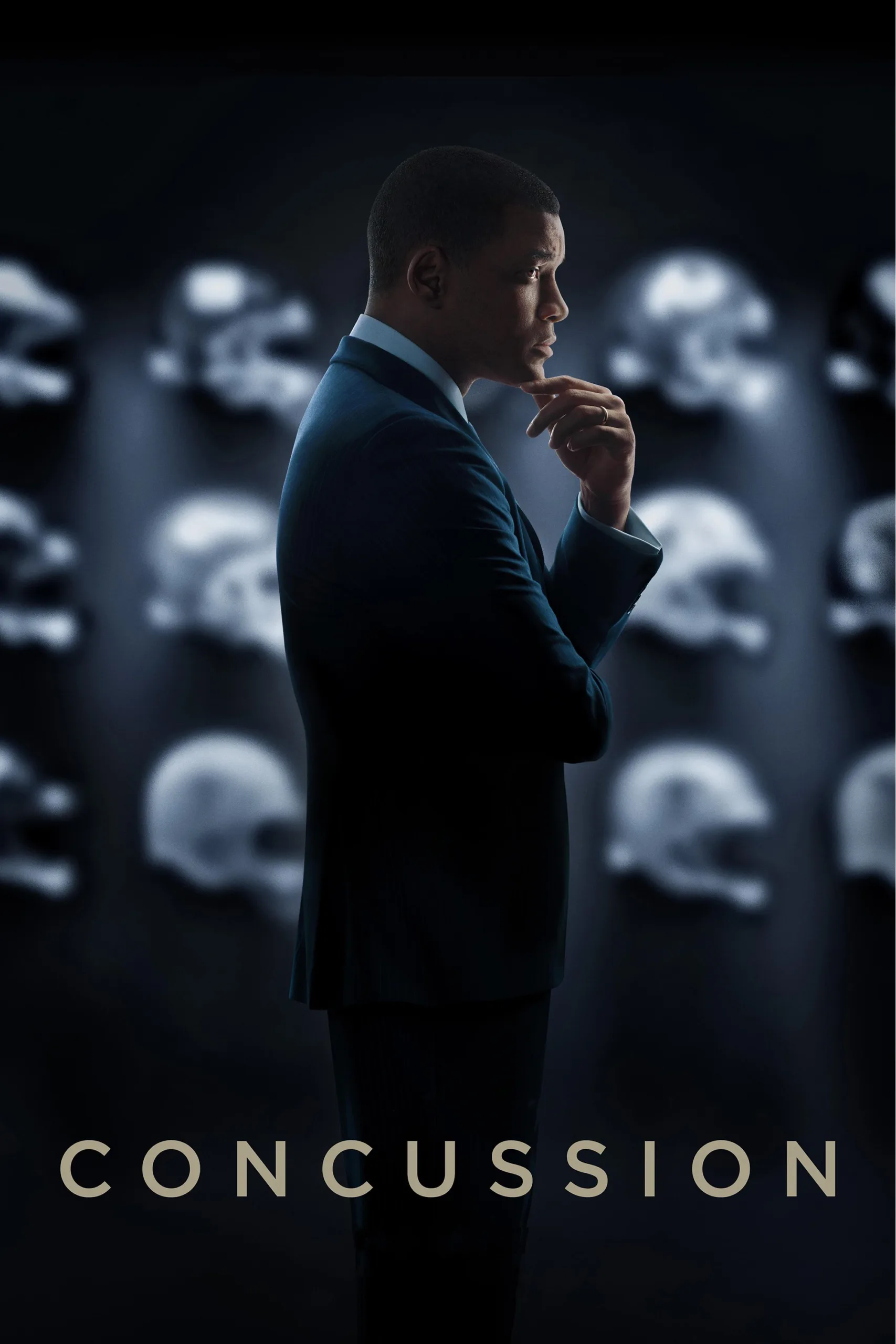

“I am the wrong person to have discovered this,” Dr. Bennet Omalu, played in this movie by Will Smith, laments to his wife Prema, near the final quarter of “Concussion.” Omalu, a practitioner who has such pride in his profession that he corrects people who refer to him as “Mister” with “Doctor,” but who is so kind-hearted, brilliant, enthusiastic and likable that the tic doesn’t play here as irritating, is in an unusually American fix in this fact-based drama.

Omalu is the real-life doctor who, while working as a forensic pathologist in Pittsburgh, discovered a new and terrifying brain disorder that he named Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, or CTE. He discovered it performing an autopsy on a retired Pittsburgh Steeler named Mike Webster (movingly portrayed here by David Morse). Webster left the game as a hero and began losing his mind well before his death at fifty; scenes shortly before his death show him living in his pickup truck, huffing turpentine. A fellow player, himself to suffer a similar fate in the movie, tries to help him out. Neither man understands what’s happening to them. Omalu figures it out: the persistent head injuries sustained in football play shake up the brain—as the character explains, unlike some other mammals, humans don’t have built-in shock absorbers for their grey matter—and release a protein that builds up and causes hallucinations, memory loss, and much more trauma.

This film, written and directed by Peter Landesman and based in part on a 2009 magazine article, portrays Omalu as a cheerful, quietly religious man who, as a Nigerian-born immigrant, believes strongly in the American Dream, and believes that doing the right thing is part of that whole trip. The response his findings elicit from the NFL quickly prove him mistaken. As Omalu’s boss and mentor, played by Albert Brooks with a nice mix of world-weariness and faith, puts it, Omalu is going up against an organization that “owns a day of the week.” Omalu thinks the NFL will be glad of his findings, and use some American ingenuity to do something about the problem. This is not what occurs.

Will Smith’s performance as Omalu is lovely: small-scaled, precise, imbued with righteousness but not tritely pious. One thing I’ve noticed when Smith essays such a performance in a movie that’s not entirely bad (and this movie is rather good): my fellow critics seem a little surprised. I don’t understand why. Even since before his first “serious” film, an adaptation of the acclaimed stage play “Six Degrees Of Separation,” he was clearly a gifted and versatile performer. Although his career in recent years has admittedly encompassed a lot of work in which he more or less merely has to “be Will Smith,” that hasn’t necessarily led to a diminishment of his chops. He’s also surrounded by expert players, including Alec Baldwin as a one-time team doctor who’s both disturbed and stimulated by Omalu’s findings, and who tries to build a bridge between Omalu and the stonewalling NFL, an effort that ends in teeth-gritting frustration.

The movie also depicts Omalu’s personal life. You know that feeling when you have no social life because you’re devoted to your work and your church, and some of the church elders ask you to provide a room from a recent immigrant from abroad, and that immigrant turns out to look just like Gugu Mbatha-Raw? No, I don’t either. But that’s what happens to Smith’s character, and soon enough Mbatha-Raw’s character, Prema, is more than a roommate. The movie treats the couple’s relationship, and their strong faith, with refreshing delicacy and respect. And Mbatha-Raw makes Prema more than a long-suffering helpmate as the hostility against Omalu and his findings begins to mount.

The movie is engaging and fascinating for much of its two hours. The editing, by Oscar-winner William Goldenberg (he won for “Argo” and also put together “Zero Dark Thirty,” for which he was also nominated), is brisk and inventive, managing to imbue excitement into montages in which Omalu is doing nothing more pulse-pounding than looking at a bunch of slides. Once Omalu finds fans, players, and the football industry itself giving him the very aggressive side-eye, the narrative begins to diffuse a bit. The movie isn’t shy about implicating that NFL chief Roger Goodell (played here by Luke Wilson) is a corporate weasel and liar. But as certain bad things begin happening around Omalu and his colleagues and his wife, things grow vague; the movie, I suppose, can’t just come out and SAY that the NFL is willing and able to do stuff that skirts “Parallax View”/”Three Days of the Condor” territory. I found that this possibly involuntary discretion worked to the movie’s advantage; the non-ratcheting up of the drama somehow made the story feel more true, more honest. The real story, in a sense, is how Omalu’s belief in the goodness of some institutions came under assault, and how he refused to become a cynic even after all that. When he’s called an American hero near the end of the movie, the truth of that phrase, as well as all the contradictions that trail in its wake, are vividly felt.