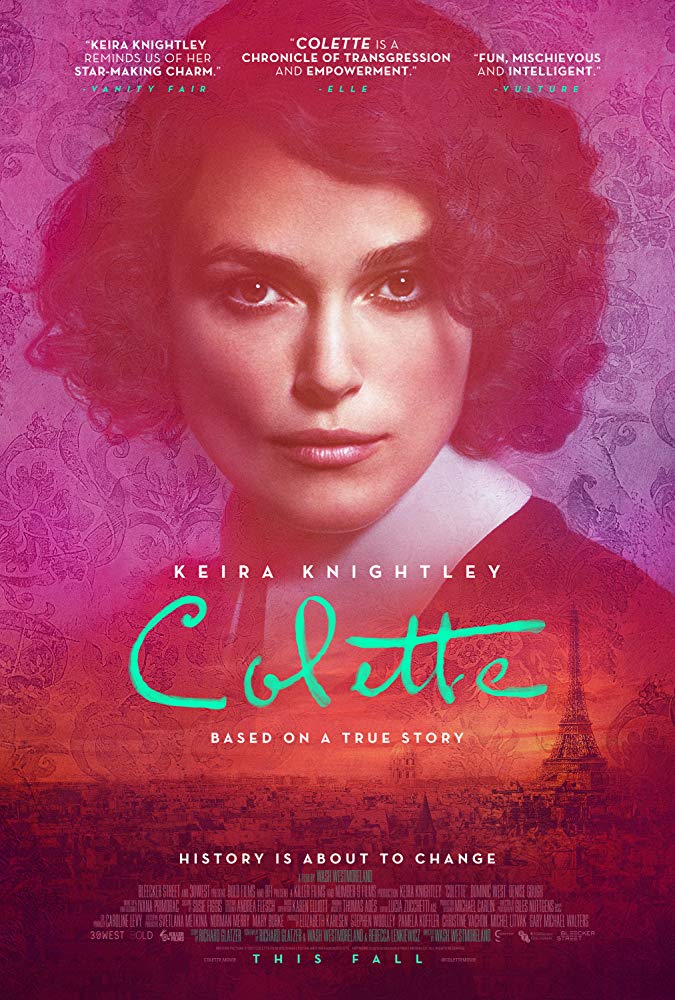

In “Colette,” based on the life of the foremost female French novelist, Giles Nuttgens’ gorgeous cinematography invites us into the lush, candle-lit world of late 19th century France, contrasting the thick greenery outdoors of the countryside with the highly decorated interiors of Paris. Both locations are seductively lavish, not in terms of the money spent by the people who live there, but in the wealth of lived-in detail bathed in soft, golden light. Colette herself, played by Keira Knightley, is in increasingly stark contrast to both settings, too curious and independent-minded for the quiet life of the country, too honest and unconfined for the conventions of the city.

We first see her as a young woman, then known as Sidonie-Gabrielle “Gaby” Colette, barely out of school. Her hair is in long braids and she appears to abide by her mother’s strict rules, though not without some grumbling. A man named Willy (Dominic West) visits from the city and presents her with a gift, a snow globe of the new Paris attraction, the Eiffel Tower. She accepts it politely, but then we see that their relationship is not the kindly uncle figure and shy schoolgirl her parents think, when after he leaves for the train she goes for “a walk.” That is what she tells her mother (Fiona Shaw). But her “walk” is straight to the barn, where she and Willy have a joyous romp in the literal hay. “Your hair is a phenomenon,” he tells her. She is a girl without a dowry, she reminds him.

But soon they are married, and the country girl finds herself in the middle of the Paris arts community, letting those who might think of her as unsophisticated know that she is bright, brave, and eager to be a part of what is going on. A snobbish acquaintance, hearing Willy is married, says, “The wild days are done, eh?” and Gaby replies with asperity, “On the contrary, the wild days have just begun.” That is truer than she knows. She expected that being married to Willy would make her “so entire and happy,” and for a while, it does. And then it does not.

When Willy can no longer afford to pay his authors, he asks Gaby to write a novel with “enough literature for the highbrows enough filth for the great unwashed—or vice versa.” He rejects her first draft as not having enough plot and being “too feminine.” But then he puts his name on her story of Claudine, a teenage girl. It becomes a sensation because of its unprecedented honesty in presenting the perspective of a young woman. Willy pushes Gaby to write sequels, even locking her in a room until she produces more pages.

Willy betrays Gaby as a wife: he explains constant infidelity is just how men are and she has to get used to it. And he betrays her as a writer: she begins to believe her own name should be on the Claudine books, which are not just her perspective, but also her own experiences.

She begins to work out what is going on in the present through the books, telling Willy, “I’m planning on killing Reynaud [the Willy character] off in the next one,” and reminding him of his own statement that “the hand that holds the pen writes the history.” Willy does his best to keep Gaby, who now wants to be known as Colette, as the young country girl he first met, even asking her to dress in Claudine’s schoolgirl uniform. But she becomes more independent, having a long-term affair with one of the many young women who insist, “I’m the real Claudine.”

Colette learns to dance and act and begins to perform on the stage. She has affairs with women (one of whom also has an affair with Willy). And she fights to put her name on her work.

The film struggles with the same challenge in all movies about writers: there is nothing less cinematic than someone sitting at a desk with brow furrowed, putting words together, even when it is with an elegant fountain pen in a gorgeous belle époque setting. It would have given the story more depth, especially for American audiences, who may vaguely only know that Colette wrote the story that inspired “Gigi,” to provide more of a sense of her work, its frankness and modernity.

But the chemistry is palpable between Knightley and West, whether they are in love or estranged, and Knightley gives one of her best performances as a girl with spirit and talent who becomes a woman with ferocity and a voice.