“Coco Chanel & Igor Stravinsky” concerns a love affair between two irresistible forces who have never met an immovable object before. The composer Igor Stravinsky and the designer Coco Chanel, defining influences on 20th century taste, consummated their attraction some seven years after they first met, perhaps because each had become so autonomous that the challenge became irresistible.

If you’ve seen “Coco Before Chanel” (2009), and I hope you have, this unrelated production takes up Chanel’s story after World War I and soon after the death of her young lover, Boy. But it begins with a scene so necessary that the romance might not make much sense without it: the historic 1913 opening night in Paris of Stravinsky’s “The Rite of Spring,” with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. The angular, hard-edged music and the bluntly discordant choreography combined to horrify the bourgeois audience, who booed, hooted, walked out and cast Stravinsky into a depression.

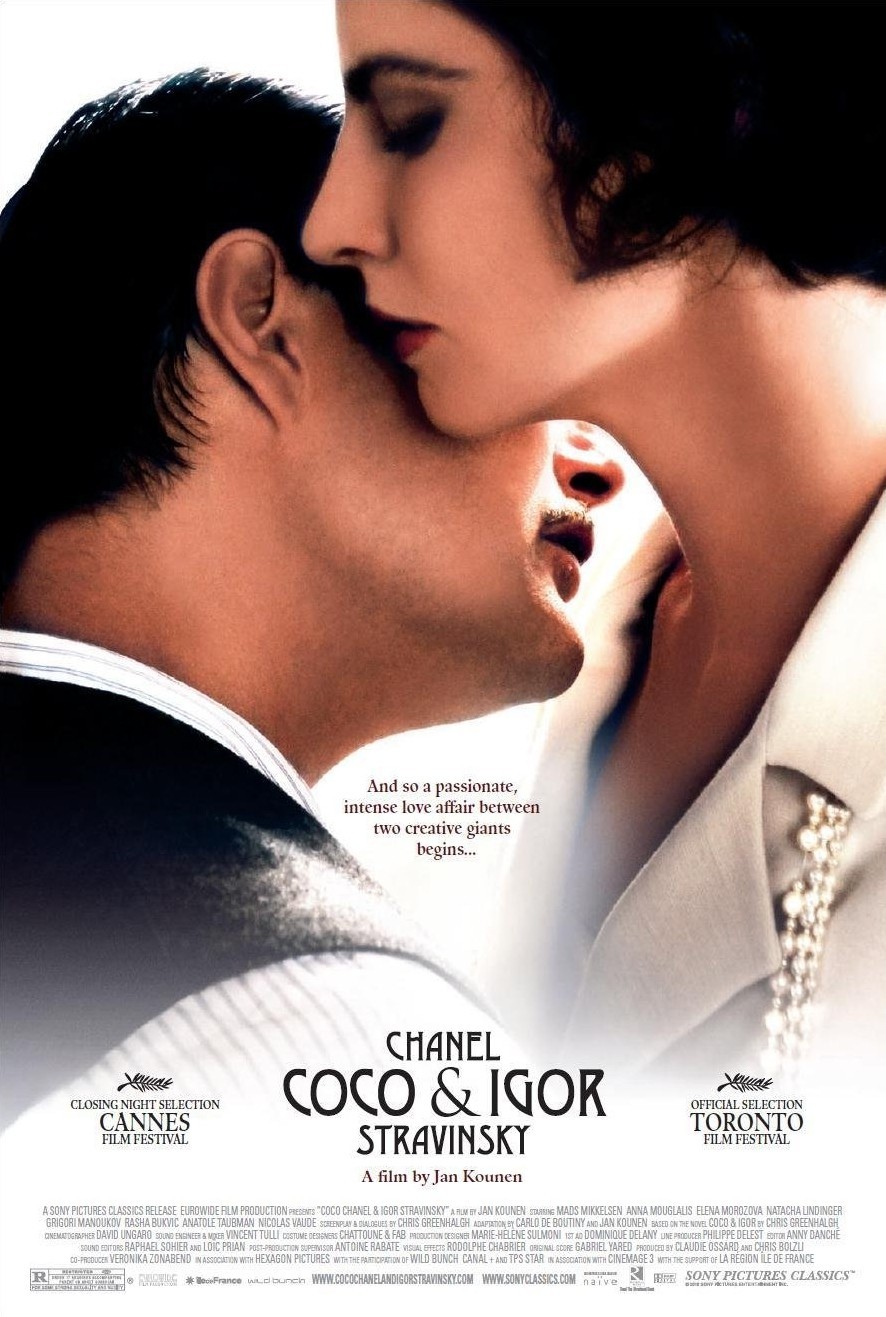

We see Chanel (Anna Mouglalis) in closeup as she watches the performance, but would be hard pressed to know exactly what she thinks. Chanel didn’t wear her heart on her sleeve and indeed barely wears her face on her face. But after the Great War, they meet again in Paris. Now Stravinsky (Mads Mikkelsen), made penniless by the Russian Revolution, is in exile with wife Katarina (Elena Morozova) and their four children. Chanel invites them to be her guests at her villa, and even at that moment, their affair is a foregone conclusion.

Stravinsky and Chanel are cool customers. There are times when their meetings seem to be wordless displays of will. They are impressed with themselves, and of course they have much to be impressed about: Neither has ever doubted or questioned their own creative genius, and the world was even then validating their judgments. Although their sex is fervent and urgent, one could not quite call it passionate; they are like artists observing their own performances from the wings.

The human element in this story, crucial, is introduced by the wife Katarina. In their arrogance, Igor and Coco barely bother to conceal their behavior, and she knows full well what is happening. She also knows, as they all probably do, that this is not true love and will not last. In the meantime, she has a home and food for her children, and her husband cannot yet produce those on his own. She is not without pride, and once asks Coco, not with anger, if she isn’t shamed by what she is doing. “No,” Coco replies, and that answer somehow reflects her dress designs, which are bold, crisp, clean, stark, arrogant, and resisting color and the flesh.

Katarina knows her husband and almost certainly understands him better than he does himself. She also understands his music and can discuss it with him, an ability there’s no evidence that Coco shares. This results in a household ménage, which is largely an exercise in Katarina’s passivity in the fact of their selfishness. Then there is always the presence of the four children, a biological fact that trumps Chanel.

Stravinsky and Chanel were great creators and influences. Between the two biopics, I gather little evidence that Chanel was a nice woman. I have sympathy for her childhood as an orphan who raised herself with her sister, but her hard start seems to have inspired feelings more of revenge than of pity. Certainly she has no problem in mistreating her employees.

The film is elegant to look at. The fashions are almost inevitably are flawless and chic. The performances are well-modulated to project exactly what the director, Jan Kounen, wants to say about these two people. He depends on performance because neither is given to self-analysis or revelation, and most of their meetings are in some way negotiations. As for Katarina, well, what can she do? She stays out of love for her children and out of undoubted respect for her husband’s genius.

There is a story about the time the publisher Bennett Cerf went to visit James and Nora Joyce in Paris. “You are married to a great man,” he told Nora, who replied: “You don’t have to live with the bloody fool.”