An interrogator and a prisoner, alone in a room. The interrogator a man, the prisoner a woman. The country, unnamed. The charge: sedition. She has written a children’s book that he believes is an allegorical attack on the state. He blindfolds her, assumes threatening personalities, browbeats her, plays mind games, and then moves along to various refinements of physical torture. She resists courageously. Being mistreated by men is nothing new for her. This very same man assaulted her when she was a child.

All it requires to make “Closet Land” complete is a pious screen note at the end of this story, assuring us that the torture of political prisoners continues all over our world today. The movie does not disappoint: The slogan appears right on schedule.

What is the politically correct response? To cry out with horror? To rush from the theater and devote my life to ending injustice? What are the makers of films like this hoping for? Their movies are never seen by the torturers, and bring no fresh news for the good of heart, who are already well aware of the corrupted world we inhabit. The movie seems intended for the already converted, as an exercise in self-congratulation. They can refresh their outrage.

The evil torturer in this movie is of course a white Western male, perhaps because he is a politically correct enemy, although most officially sanctioned torture today takes place in the Middle East, Asia, Africa and South America. The victim is of course a woman, although most political prisoners are men (in many of the countries where official torture prevails, women are not permitted sufficient freedom of movement to become politically dangerous). I am of course opposed to torture, but I preserve sufficient irony to be offended by the smugness of this film.

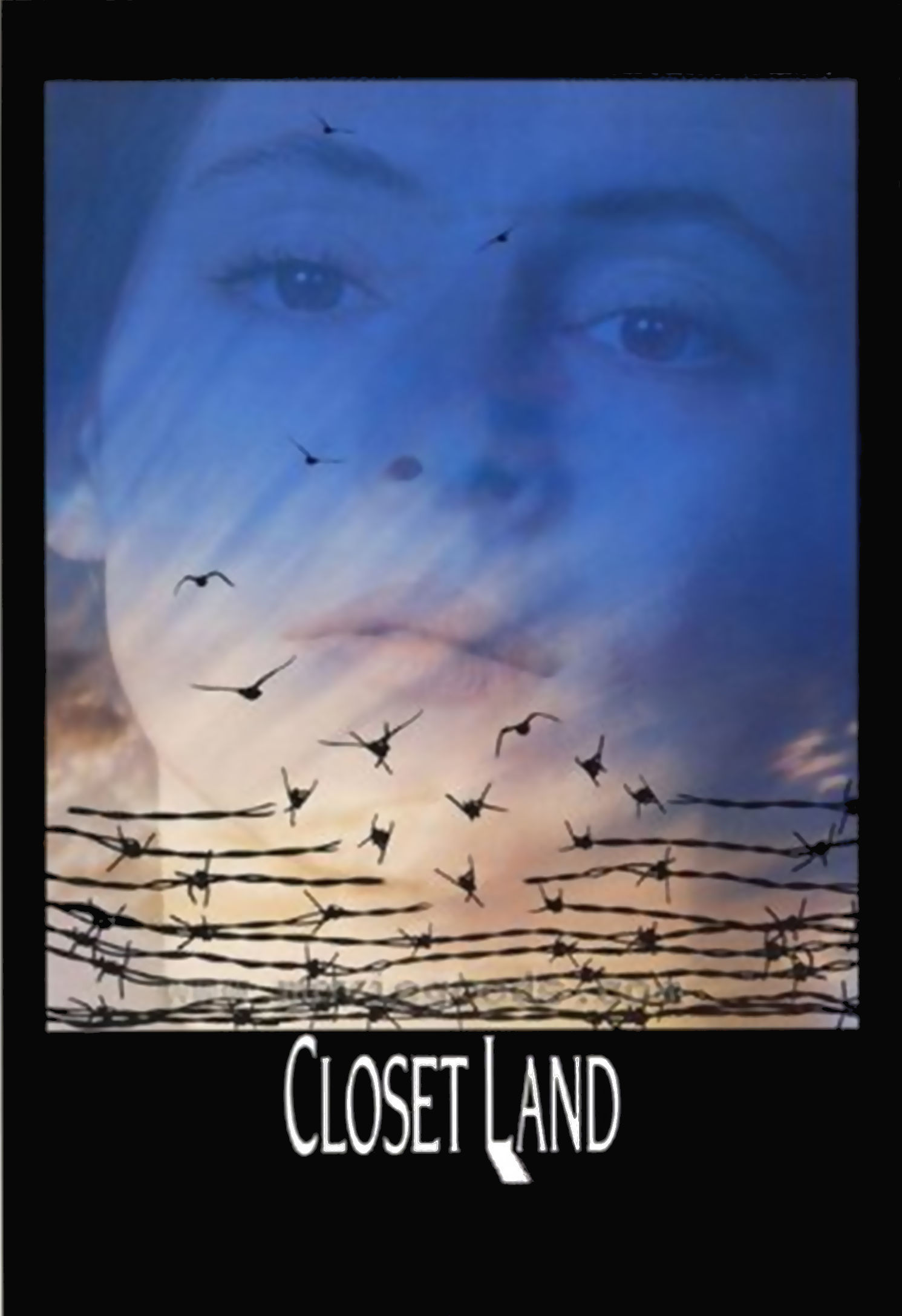

The story takes the form of a long dialogue between the man, who is known as “Man,” and the woman, who is known as “Woman.” She is played by Madeleine Stowe, the heroine of “Stakeout,” and he is played by Alan Rickman, the man who held the building hostage in “Die Hard.” She has written a book in which a young girl locked in a closet escapes into her mental fantasies. He sees the book as an attack on the society he represents – although neatly, too neatly, he knows that as a small girl she used such fantasies as a means of escaping from his own sexual attentions. The tyranny of rape and of the state are thus combined in one tidy symbolic package.

Man and Woman are enclosed in a space which could be called Space. Its pillars and vistas divorce the characters from any particular time and place. But this is not a simple allegory; we are given details of the Woman’s fantasies, as they exist in her books and mind, and so we are forced to wonder if she would really be treated this way in any world other than the manipulated one of this movie.

The film was written and directed by Radha Bharadwaj, who was inspired, I understand, by her commitment to Amnesty International. I have no doubt it is a labor of love, but there is a temptation to praise films like this because of their noble sentiments, without asking whether the work is good filmmaking. Is is possible to be against political torture and still dislike this film? I think it is. I was particularly unconvinced by the ending of the film, in which Woman prevails for no better reason than that she is Woman, and the fight was fixed. She absorbs all the mental and physical abuse Man can throw at her, and finally defeats him through her capacity to absorb more suffering than he is willing, or able, to administer. The film would have been truer to itself and the real world if at the end the man had simply executed her.

Prisoners do not often defeat their captors simply through an indomitable will – especially when the villains hold the trump card of death.

Man is indeed inhuman to man, and woman, in this world.

Often that is because we are seduced by rigid ideological righteousness, ignoring the admonition that we should do unto others as we would have them do unto us. If you think you are Right and others are Wrong, it takes only a small step to rationalize doing wrong to others. One way to take that step is to objectify others into the personification of evil. “Closet Land” is an exercise in that process, and not nearly as nice a movie as it thinks it is.