Mike Nichols‘ “Closer” is a movie about four people who richly deserve one another. Fascinated by the game of love, seduced by seduction itself, they play at sincere, truthful relationships which are lies in almost every respect, except their desire to sleep with each other. All four are smart and ferociously articulate, adept at seeming forthright and sincere even in their most shameless deceptions.

“The truth,” one says. “Without it, we’re animals.” Actually, truth causes them more trouble than it saves, because they seem compelled to be most truthful about the ways in which they have been untruthful. There is a difference between confessing you’ve cheated because you feel guilt and seek forgiveness, and confessing merely to cause pain.

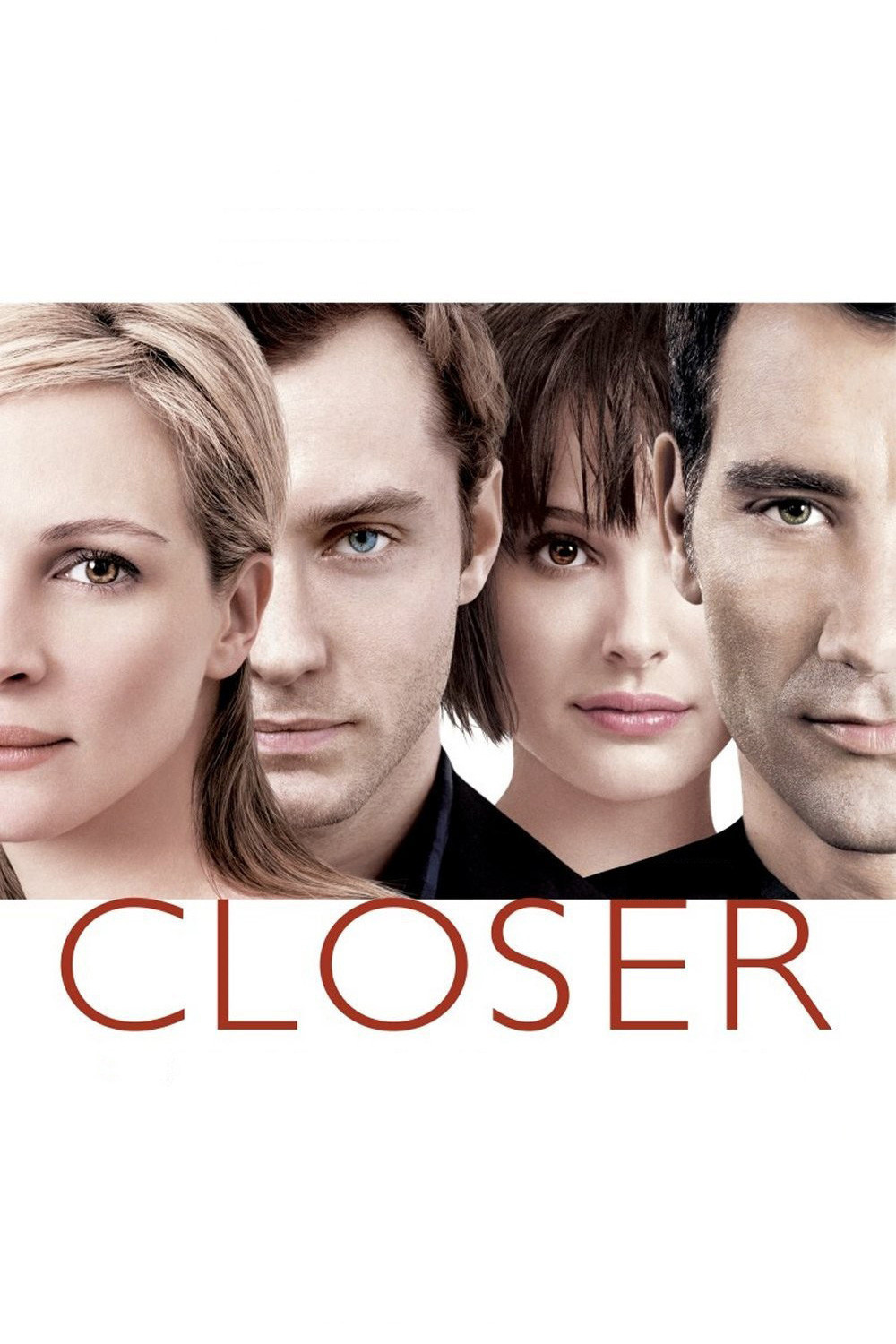

The movie stars, in order of appearance, Jude Law, Natalie Portman, Julia Roberts and Clive Owen. Law plays Dan, who writes obituaries for his London newspaper; Portman is Alice, an American who says she was a stripper and fled New York to end a relationship; Roberts is Anna, an American photographer; and Owen is Larry, a dermatologist. The characters connect in a series of Meet Cutes that are perhaps no more contrived than in real life. In the opening sequence, the eyes of Alice and Dan (Natalie Portman and Jude Law) meet as they approach each other on a London street. Eye contact leads to an amused flirtation, and then Alice, distracted, steps into the path of a taxicab. Knocked on her back, she opens her eyes, sees Dan, and says “Hello, stranger.” Time passes. Dan writes a novel based on his relationship with Alice, and has his book jacket photo taken by Anna, who he immediately desires. More time passes. Dan, who has been with Anna, impersonates a woman named “Anna” on a chat line, and sets up a date with Larry, a stranger. When Larry turns up as planned at the aquarium, Anna is there, but when he describes “their” chat, she disillusions him: “I think you were talking with Daniel Wolf.”

Eventually both men will have sex with both women, occasionally as a round trip back to the woman they started with. There is no constancy in this crowd: When they’re not with the one they love, they love the one they’re with. It is a good question, actually, whether any of them are ever in love at all, although they do a good job of saying they are.

They are all so very articulate, which is refreshing in a time when literate and evocative speech has been devalued in the movies. Their words are by Patrick Marber, based on his award-winning play. Consider Dan as he explains to Alice his job writing obituaries. There is a kind of shorthand, he tells her: “If you say someone was ‘convivial,’ that means he was an alcoholic. ‘He was a private person’ means he was gay. ‘Enjoyed his privacy’ means he was a raging queen.”

Forced to rank the four characters in order of their nastiness, I would place Dr. Larry at the top of the list. He seems to derive genuine enjoyment from the verbal lacerations he administers, pointing out the hypocrisies and evasions of the others.

Dan is an innocent by comparison; he wants to be bad, but isn’t good at it. Anna, the photographer, is accurately sniffed out by Alice as a possible lover of Dan. “I’m not a thief, Alice,” she says, but she is. Alice seems the most innocent and blameless of the four until the very end of the movie, when we are forced to ask if everything she did was a form of stripping, in which much is revealed, but little is surrendered. “Lying is the most fun a girl can have without taking her clothes off,” she tells Dr. Larry, “but it’s more fun if you do.”

There’s a creepy fascination in the way these four characters stage their affairs while occupying impeccable lifestyles. They dress and present themselves handsomely. They fit right in at the opening of Anna’s photography exhibition. (One of the photographs shows Alice with tears on her face as she discerns that Dan was unfaithful with Anna; that’s the stuff that art is made of, isn’t it?) They move in that London tourists never quite see, the London of trendy restaurants on dodgy streets, and flats that are a compromise between affluence and the exorbitant price of housing. There is the sense that their trusts and betrayals are not fundamentally important to them; “You’ve ruined my life,” one says, and then is told, “You’ll get over it.”

Yes, unless, fatally, true love does strike at just that point when all the lies have made it impossible. Is there anything more pathetic than a lover who realizes he (or she) really is in love, after all the trust has been lost, all the bridges burnt and all the reconciliations used up?

Mike Nichols has been through the gender wars before, in films like “Carnal Knowledge” and “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf.” Those films, especially “Woolf,” were about people who knew and understood each other with a fearsome intimacy and knew all the right buttons to push.

What is unique about “Closer,” making it seem right for these insincere times, is that the characters do not understand each other, or themselves. They know how to go through the motions of pushing the right buttons, and how to pretend their buttons have been pushed, but do they truly experience anything at all except their own pleasure?