Wang Xiaoshuai’s latest movie works so splendidly on its own self-contained and easily divined terms you could watch it without knowing anything about the Shanghai-born director and still walk out stunned. Of course, the payoff of this work is all the richer if you know the course the director took from studio misfit beleaguered by distribution and self-esteem problems to well-liked and promising director of “Beijing Bicycle”—the kind of neo-Neo-realism international film festivals still love—to wave-riding miserablist director of scoring studies of casualties of China’s cultural revolution. He leaned more heavily on a depressive longing and woozy inevitability than did, say Jia Zhangke, to name one of the better known directors from the period known as China’s Sixth Generation. Life haunts the characters in his movies, who only realize what they’ve had to live with when looking back at who they were. His characters watch from the outside as tides wash over their existences, precious things are stolen, glories forgotten, potentials smothered. His two latest seem to share nothing but Wang’s sharp eye and melancholy form, but they’re instructive about the kind of cinema with which he’s wrestled all his life.

Wang’s latest is the gargantuan Golden Bear-winning family drama “So Long, My Son,” which follows two families for 30 years, charting the aftermath of the cultural revolution and the period in which Wang began making his own art. “Chinese Portrait” is like the minimalist B-side to that monumental work and it’s disarmingly simple in its methodology, one suspects because to film people simply, one must have been quite the reprieve for the dogged social realist. To spill the blood and mine the tears of forgotten men in a country grey with industry, where no life matters beyond the labor it can provide, is a burden even as it gives an artist the world. “Chinese Portrait” spends time with the real people his movies were based on in the places they’re rarely seen. He pulls out the incident and characters that color his cinema and places them back in the context from which he plucked them, deconstructing his world like he were spreading the parts of a car on a garage floor.

“Chinese Portrait” is comprised of about 60 non-fiction vignettes. In many of them there are groups of people who remain stationary and some who look directly to camera, letting the audience know that the scene isn’t exactly purely objective. In other words Wang had to pose them, at least to an extent. The business that goes on around the lone “subjects” still feels spontaneous, like he had an agreement with just a couple of people and assured the rest of the people in frame that they could ignore the camera. Some of them do feel like traditional portraits brought to life, like the group of children standing with their minder in front of a remote village, neither moving nor smiling, as if waiting for a single picture to be taken. They’re all rewarding, in compositional terms, as the errant components flutter past the steadiness of his fixed figures and the somber backdrops.

Critic Michael Sicinski has already pointed out Wang’s debt to documentarians James Benning, Peter Hutton and Nikolaus Geyrhalter, building on his pronounced affection for Andrei Tarkovsky to an anxious study of momentum and stasis as the essential tension of the people he’s filming. The new reference points help him suggest in blocking and framing what it costs us to stop being productive. In essence it’s the refusal of the action around the people staring at the camera that is the one constant. Everything else changes, from the cameras he uses to the year (it was shot over a decade). Even the most desolate of villages and workplaces display progress, whether in the form of men tending great yawning furnaces in factories or men dotting the corners of the frame like ants going about their business. One of the few compositions with no active participants shows people walking in the bottom third of the screen on a muddy path. Behind them in the middle third are old cars, a crumbling series of houses, and an excavator digging up the earth to make room for new developments, represented by the stark and unappealing apartment complexes in the top third. The film can, in just a few seconds, tell you everything you need to know about the China Wang sees; a mud-slicked construction site where promise is perpetual and no one ever just gets to live.

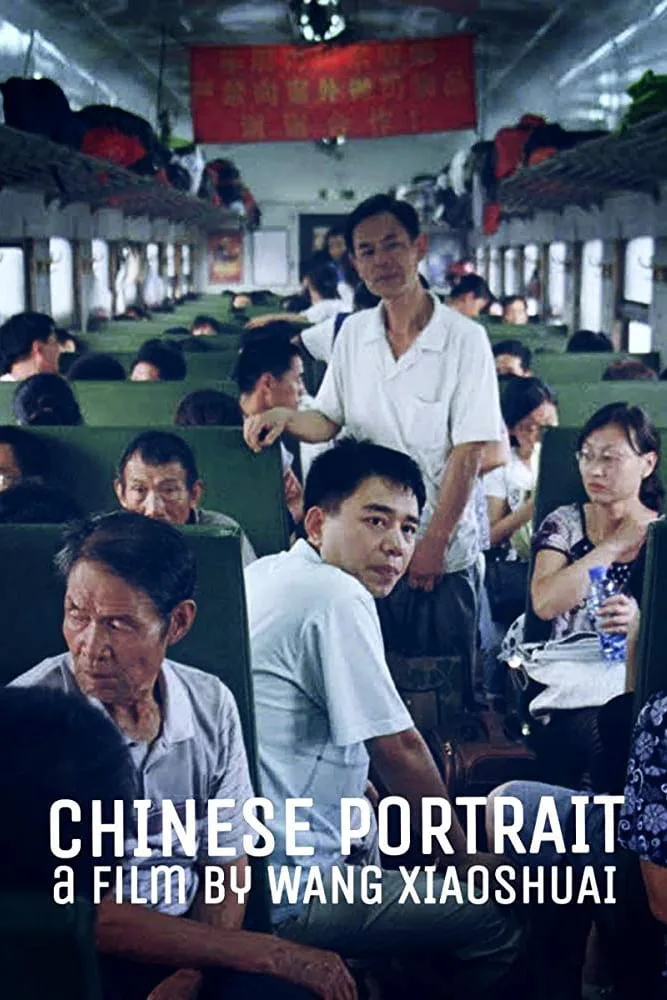

This documentary is in many ways a self-portrait as well as a look outward. Wang himself appears on camera a few times, including on a train looking at the camera, a cigarette in his hand, his homeland flying by out the open window behind him. His movies have always been about the way progress and constant “revolution” makes his characters feel small and out of place. Here he shows himself in their stead, trying to pay tribute to the place and the people who, like him, are dwarfed by the towering currents and endless drive. Even when he sets foot outside the populous towns and cities and finds horses in a field, they’re biting each other’s fur in a funny embrace, scratching an itch they can’t get to. The few minutes Wang captured are of people ignoring the motion all around them seem radical in the face of the dehumanizing effect of progress, the bane of his cinema’s existence. Staring at a camera, confronting us in the audience, asking us wonder what if anything is normal about life in a modern civilization constantly dredging up and rebuilding itself. Where does the self fit into the endless momentum? Wang asks us to construct the inner lives of the students staring at us while their classmates do their work, the men stitching fishing nets on the dock, the man in the hardhat with his back to the construction vehicle making more buildings to accommodate more people. As Wang’s China grows past predictions about its growth and government, as each corner of the country becomes impossible to film without the drapery of moving bodies and their shadows, what becomes of everyone’s identity?

My personal favorite of all of the many compositions here is the first, in which nine men in drab uniforms and miners’ helmets lean and crouch around a length of track bisecting the frame. Some of their faces are hard to make out thanks to the shadow of the mine itself or because they’re a little too far from the camera, but the way they stand is telling about their outlooks, the way they’re used to their jobs. Suddenly a length of cable starts moving and it becomes clear they’re watching as something is being pulled up from the mine out into the light. There’s no little suspense generated by the anticipation. What’s coming up from inside the earth? Probably nothing exciting, but the speed increases and these men just stand there watching. Just when it feels like the payload has to enter the frame, there’s a few small light leaks in the film and then it cuts. The reward for their efforts is unknowable to us, and suddenly their nonchalant stances seem political. Their rewards for their efforts are unknown to them, too, as this work will manifest nothing else but more work. “Chinese Portrait” is a stunning work of photography and a simple work of empathy that asks, “How much goes into making sure we all get to just live?” The world, our lives, will get away from us, this is almost certain. Stopping and simply staring at your surroundings, dreaming the interior lives of the people we pass, imagining the hard labor that went into sculpting every place we stand, it may seem like a small thing. But today it’s one of the only things that seems truly revolutionary.