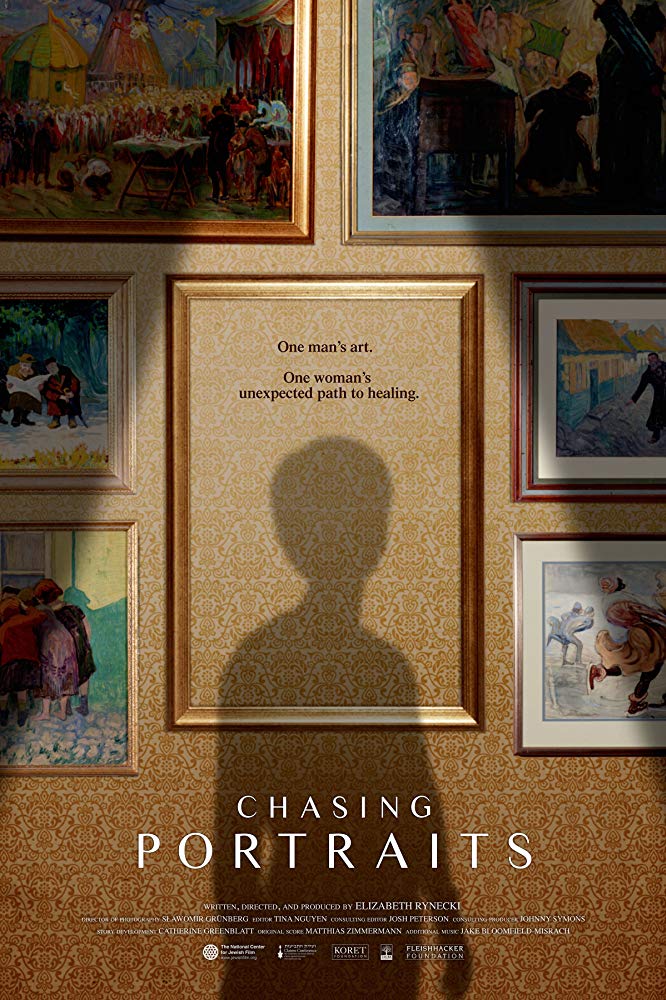

The documentary “Chasing Portraits” details the personal journey undertaken by director Elizabeth Rynecki, who spent the last decade in pursuit of her great-grandfather, Moshe’s artwork. The elder Rynecki was a prolific painter in his native Poland, turning out numerous depictions of the lives of Polish Jews before World War II. When Hitler rose to power, Moshe’s son, George was able to pass in order to keep his wife and children from being sent to the Polish ghettos. However, Moshe’s tie to his community was too strong for him to leave it. He remained in the Warsaw ghetto until he was eventually killed by the Nazis at the Majdanek concentration camp.

After the war, Moshe Rynecki’s wife would recover 120 of his 800 paintings, which were now historical snapshots of the Polish-Jewish way of life that had been destroyed by the Holocaust. Several other pieces of his artwork would end up in places as prestigious as a Jerusalem art museum and as personal as a private art collector’s wall. “We think we have a legitimate claim to some of these paintings,” Elizabeth’s father, Alex says while showing some of the rescued materials he owns.

But “Chasing Portraits” is ultimately not about Elizabeth’s attempt to retrieve or reclaim the works for her family. Rather, she explores how these items wound up where they did, and whether they should remain where they are. In pursuing these questions, the film touches on issues like artistic intent. After all, Moshe Rynecki’s art is such a love letter to his people that he must have wanted them to see it, no matter where it was. It meant so much to him that he hid it away from the Nazis for safekeeping.

The family’s collection of paintings had always intrigued the young Elizabeth. Her grandmother endured the difficult task of trying to collect as much as she could after the war. As an adult, Elizabeth started a website documenting Moshe’s output. After ramping up her social media presence, she was invited to speak to several Jewish groups about her family history and her quest to discover lost artwork. These events led her to her hearing from people who were in possession of Moshe’s work.

We meet several of these people in “Chasing Portraits,” starting with Moshe Wertheim, a Polish ex-pat now living in Toronto. He agrees to let Elizabeth see the four paintings he owns, one of which was almost destroyed due to its controversial nature. He and his brother inherited Moshe’s pieces from his parents which, according to Wertheim’s story, were sold to his folks by Polish farmers after the war. Wertheim gives Elizabeth his brother’s address in Poland so that she may talk with him as well. She finds the story rather suspicious—why would poor people who were walking back to Poland from Russia after the war suddenly decide to buy artwork? Later, when she meets the brother, he tells a completely different story.

Unlike many people researching their ancestry, Elizabeth had several pieces of information. For starters, George Rynecki had documented his life in a memoir he’d written. “He seemed to answer questions he knew I’d ask,” narrates Elizabeth, including writing about his own attempts to locate lost paintings. She has her father, who was 3 when the Nazis took over and can provide a lot of firsthand information even though revisiting his past clearly causes him discomfort. Unlike his curious daughter, Alex has no desire to revisit his homeland, and while I understand her desire to connect with her past, I found Elizabeth’s prodding of her father to be rather troublesome at times. To her credit, her camera records her father’s uncomfortable reactions (there’s great power in his moments of silence as he navigates memories the viewer can’t remotely imagine). Alex’s willingness to soldier on for the sake of future generations of his brood knowing their history is inspiring.

This is a very personal documentary that occasionally has the intentional feel of a home movie. The director gives her camera to her father and her son, who film her asking questions or describing things, and she doesn’t edit out the little mistakes you’d expect to be removed. I wasn’t bothered by the visual techniques employed. I thought they were entertaining. But the film’s narrow scope prohibited a deeper probe of ideas I thought were worth investigating. The Warsaw section of the film feels protracted, for example, with Elizabeth broaching and then dropping ideas like Jewish artwork being looted post-WWII and anti-Semitic trinkets being currently sold on the street under the guise of mementos.

Additionally, the constant narration makes the film feel too much like a podcast. If podcasts drive you crazy (they make me want to scream) or if this type of documentary bothers you, “Chasing Portraits” will not be your cup of tea. But I’m giving it a favorable review because I felt a strong connection to the director’s desire to bond with her ancestors through art. So much of what I know about who I am was passed down to me through stories I grew up hearing. Those stories, passed from generation to generation, gave me a feel for the traumatic and often joyful lives of those who came before me. Elizabeth Rynecki’s understanding comes from pictures rather than words, but I still felt enough kinship to bump this up to three stars. Your mileage may vary.