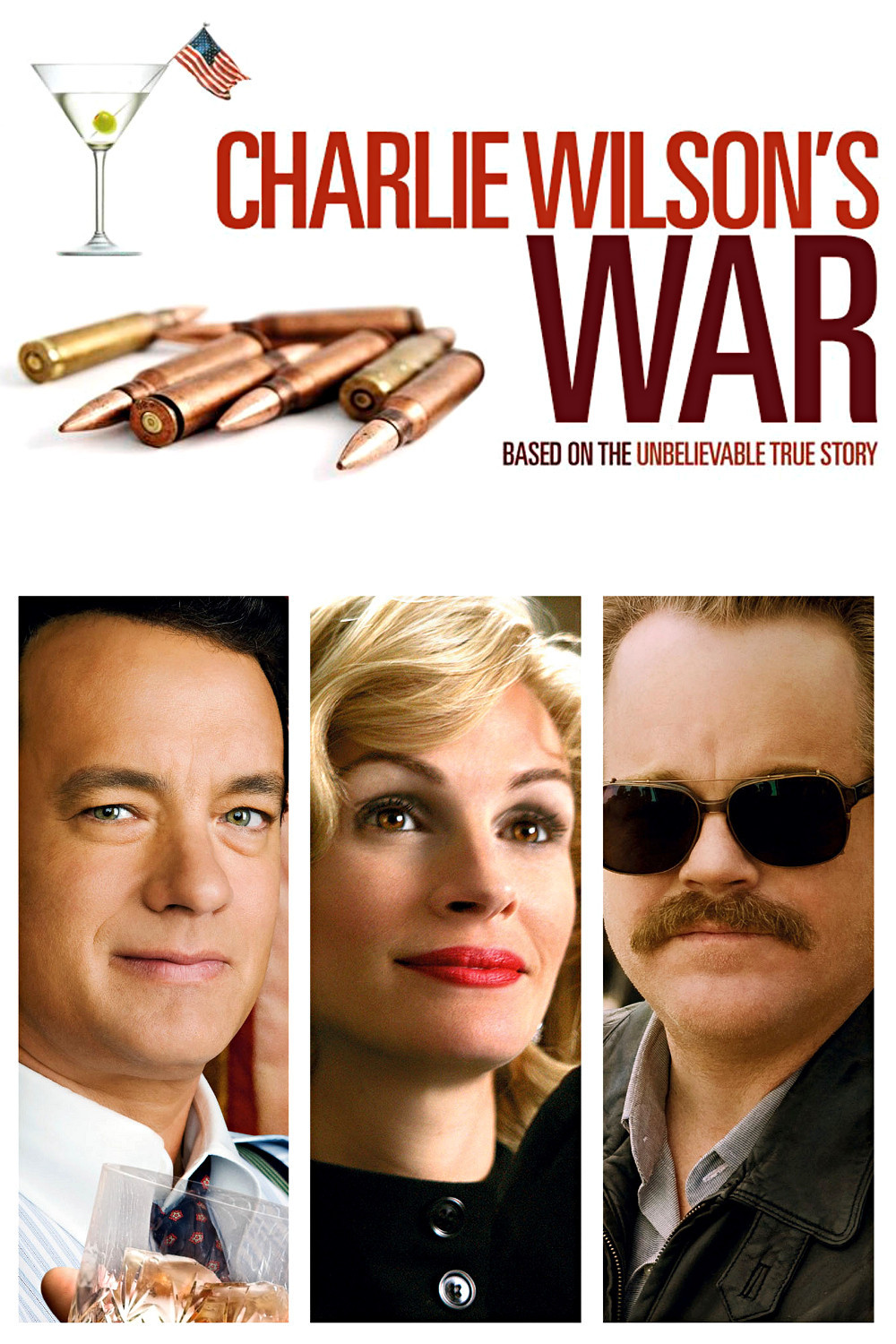

“Charlie Wilson’s War” is said to be based on fact, and I have no reason to doubt that. It stars Tom Hanks as Rep. Charles Wilson, a swinging, hard-drinking, coke-using liberal Democrat from Texas who more or less single-handedly defeated the Russians in Afghanistan. Yes. The Soviets withdrew in 1989, the Berlin Wall fell, the Cold War was over, and Ronald Reagan got all the credit. How could Wilson’s operation have taken place without anyone knowing? If Ollie North’s activities could, why not these?

Here’s how it all happened, told in a sharp-edged political comedy directed by Mike Nichols and written by Aaron (“The West Wing”) Sorkin. Charlie Wilson, whose personal life was shall we say untidy, was popular in the 2nd Congressional District of Texas because he never met a pork-barrel project he didn’t like, especially if it meant federal funds for the 2nd Congressional District of Texas. Apart from that, nobody back home much cared that he was a good ol’ boy who liked company in a hot tub and was rarely without a drink in his hand.

He had a soft spot for a right-wing Houston millionaire socialite named Joanne Herring (Julia Roberts), a sometime TV talk-show hostess, who hated the commies and wanted them to stop killing the brave Afghans. She had some connections, since she was an honorary consul to Pakistan.

She told Charlie the Afghans need weapons to shoot down Russian helicopters. Since he was on the Defense Appropriations Subcommittee, he was ideally placed to help them. Problem was, the United States couldn’t afford to have American-made weapons found in Afghanistan. Herring’s solution: The Israelis had lots of shoulder-mounted Soviet-made anti-aircraft weapons, which they could supply to the Afghans through the back channel of Pakistan? What? asks Charlie. Pakistan and Israel working together?

Herring arranges for Wilson to meet her personal friend General Zia, the military dictator of Pakistan, who hates the Russians as much as she does. Zia sends him on a heartbreaking tour of Pakistan’s refugee camps for displaced Afghans. Charlie finds the one man in the CIA who can actually help him: The pot-bellied, chain-smoking, hard-drinking outsider Gust Avrakotos (Philip Seymour Hoffman, with a squirrelly little mustache. Gust knows just the Israeli for them to talk to.

They will need money. The United States was then supplying the Afghan freedom fighters with a useless $5 million a year, but Charlie was a master at glad-handing, elbow-bending and calling in favors, and that amount was quietly raised to $1 billion a year, all secret, because it was CIA funding, you see. With the use of some personal diplomacy and a Texas belly-dancer flown from Houston to Cairo, Charlie pulls off the deal.

All true, they say. Mrs. Herring, who was earlier Mrs. King and later Mrs. Davis, even agrees. Check out her Web site: joanneherring.com. She was born in a house modeled on Mt. Vernon, and looks not totally unlike Julia Roberts. What is remarkable about the collaboration of Nichols and Sorkin is that they make this labyrinthine scheme not only comprehensible but wickedly funny, as Charlie Wilson uses his own flaws and those of others to do a noble deed. Well, it was noble at the time, although unfortunately, the “freedom fighters” later became the Taliban, and some of those weapons were no doubt used against American helicopters. As the man says, you can plan plans, but you can’t plan results.

You might think Tom Hanks is miscast as the lovable sinner. Dennis Quaid, maybe, or Woody Harrelson. But Hanks brings something unique to the role: He plays a man spinning his wheels, bored with the girls and parties, looking for something to bring meaning to his slog through the federal bureaucracy. He and Gust (a perfect name) are well-matched. “Do you drink?” he asks the CIA man on their first meeting. “Oh, God, yes.” Gust has been fighting for years to budge the CIA on Afghanistan, and now the right congressman falls into his hands.

Nichols fills the edges of the screen with unforced humor. There are “Charlie's Angels,” Wilson’s office staff of buxom young women, all of them smart. There’s Charlie’s special assistant Bonnie, played by the lovable, fresh-faced Amy Adams (“Junebug,” “Enchanted“), who cleans up after him, gives him good advice, keeps his schedule, and adores him. And there is the presence of Hoffman himself, a smoldering volcano of frustration and unspent knowledge. It’s hard to see how Charlie could have ended the Cold War without him, and impossible to see how Gust and Bonnie could have ended it without him. The next time you hear about Reagan ending it, ask yourself if he ever heard of Charlie Wilson.