Farm worker organizer and union activist Cesar Chavez today is a man with many streets named after him but little purchase on the public memory, outside, perhaps, of the Latino community. So it’s understandable that filmmakers would want to dramatize a life and career that were not only politically potent but inspirational to many. Unfortunately, “Cesar Chavez,” directed by Mexican actor Diego Luna, commits the classic sin of biopics about storied leaders: it’s reverential rather than revealing, predictably admiring where it needs to be nuanced and challenging.

Biographies of Chavez paint a man who was complex and controversial even within his own circle, a natural leader who also made strategic mistakes that sometimes harmed his own cause. This is rich material for a movie. Yet “Cesar Chavez” regrettably gives us the historical man with all the rough edges sanded off, leaving a depiction that bears an uncomfortable resemblance to a plaster saint.

Although the film concentrates on the period from 1965-1970, when Chavez led a strike of grape-farm workers that brought him into the national media glare, it begins by sketching the years before he landed on the cover of Time. Born in Arizona of Mexican descent, he labors as a farm worker after his family moves to California. By his mid-20s he’s working as an organizer for the Community Service Organization, a Latino civil rights group, when the hard conditions faced by farm workers compels him to move his young family to a farming community to take up the cause.

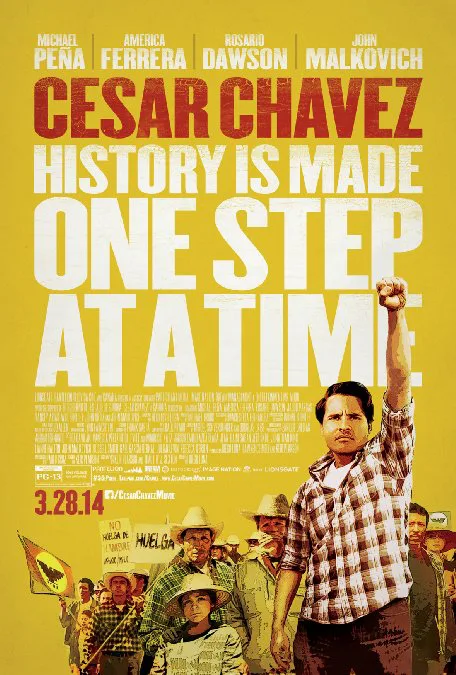

One of the first challenges facing him is the antipathy between Filipino and Latino workers. Making the case that the owners always pit different ethnic groups against each other, Chavez (Michael Peña) succeeds in forging an alliance. Throughout, he urges non-violence even in situations where the angry owners aren’t hesitant to employ goons and firearms. After organizing the workers, with the help of activist Dolores Huerta (Rosario Dawson), he leads a march on Sacramento that draws national attention, and launches a boycott of California grapes that’s taken up by consumers across the country.

Eventually Chavez gains a powerful ally in Senator Robert F. Kennedy (Jack Holmes), who comes to California while engaged in congressional hearings. Despite his growing fame, the union leader risks both his health and his credibility by undertaking a hunger strike. And after Kennedy’s assassination, Chavez faces a much chillier political climate when anti-union leaders like Ronald Reagan and Richard Nixon hold sway in the U.S.

While Keir Pearson and Timothy J. Sexton’s script chronicles these events in a very straightforward, sometimes numbingly literalistic fashion, it also leaves too much unclear. When the farm workers go on strike, what exactly are they demanding? What kinds of wage increases or improved conditions? A little specificity in the details of these struggles would have helped viewers understand them far better, which in turn would have helped them feel less generalized and more genuinely dramatic.

But the script’s vagueness is most problematic when it comes to the movie’s central figure. How did Chavez come by his pacifistic convictions and tactics? Was he influenced by Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr. or his own Catholic upbringing? Did his colleagues in the movement ever challenge him with their own ideas rather than just accepting his? None of this do we ever learn in “Cesar Chavez,” which presents its hero as a fully-formed wise man rather than a complicated, growing individual who learns from others and from his own difficult experiences.

Ironically, the film’s most arresting character is Chavez’s political opposite number, a sneering right-wing grower named Bogdonovitch, who’s played with pungently malevolent gusto by John Malkovich. You don’t need a press kit to deduce that this man is a “composite”–i.e., fictional–character. The moviemakers faced the choice between inventing their villain or facing a lawsuit from a real-life miscreant, no doubt, and they made the obvious choice. But the result is that Bogdonovitch and Chavez seem like they belong in two different movies. One has all the vividness and density of potent fiction, where the other is as pallid and dimensionless as a news brief.

Some of this, of course, has to do with the acting. While Luna proves an able director in mounting scenes in a fluidly realistic manner and flavorfully evoking the story’s mostly rural period settings (in which California is played by Mexico), he also must share blame for the blandness of Chavez’s portrayal. An extremely capable and appealing actor in most circumstances, Michael Peña here seems both hemmed in and weighed down by the halo that’s almost visible above his head. His work feels predetermined where it needs to be probing, respectful where it needs riskiness.

The shame of this is that “Cesar Chavez” comes off as a wasted opportunity precisely because it does successfully return us to an era of important political change. Once upon a time, ordinary white housewives heeded the call of a Latino union leader and boycotted California agricultural products to the point of forcing an industry to change its labor practices. Would such a thing be possible today, and if not, why not? The film inevitably sends viewers away with such questions stirring in their minds. Yet its final failing is that it does nothing to connect those long-ago events and today, when Latinos are a far more influential politically and immigration and farm labor are still hot-button issues. It’s too content to let the history lesson it gives us remain only that: history.