In the Brazilian documentary “Bus 174,” there is a scene that could have been shot in hell. Using the night vision capability of a digital camera, the film ventures into an unlit Brazilian prison to show desperate souls reaching through the bars. Jammed so closely they have to sit down in shifts, with temperatures above 100 degrees Fahrenheit, with rotten food and dirty water, many jailed without any charges being filed, they cry out for rescue.

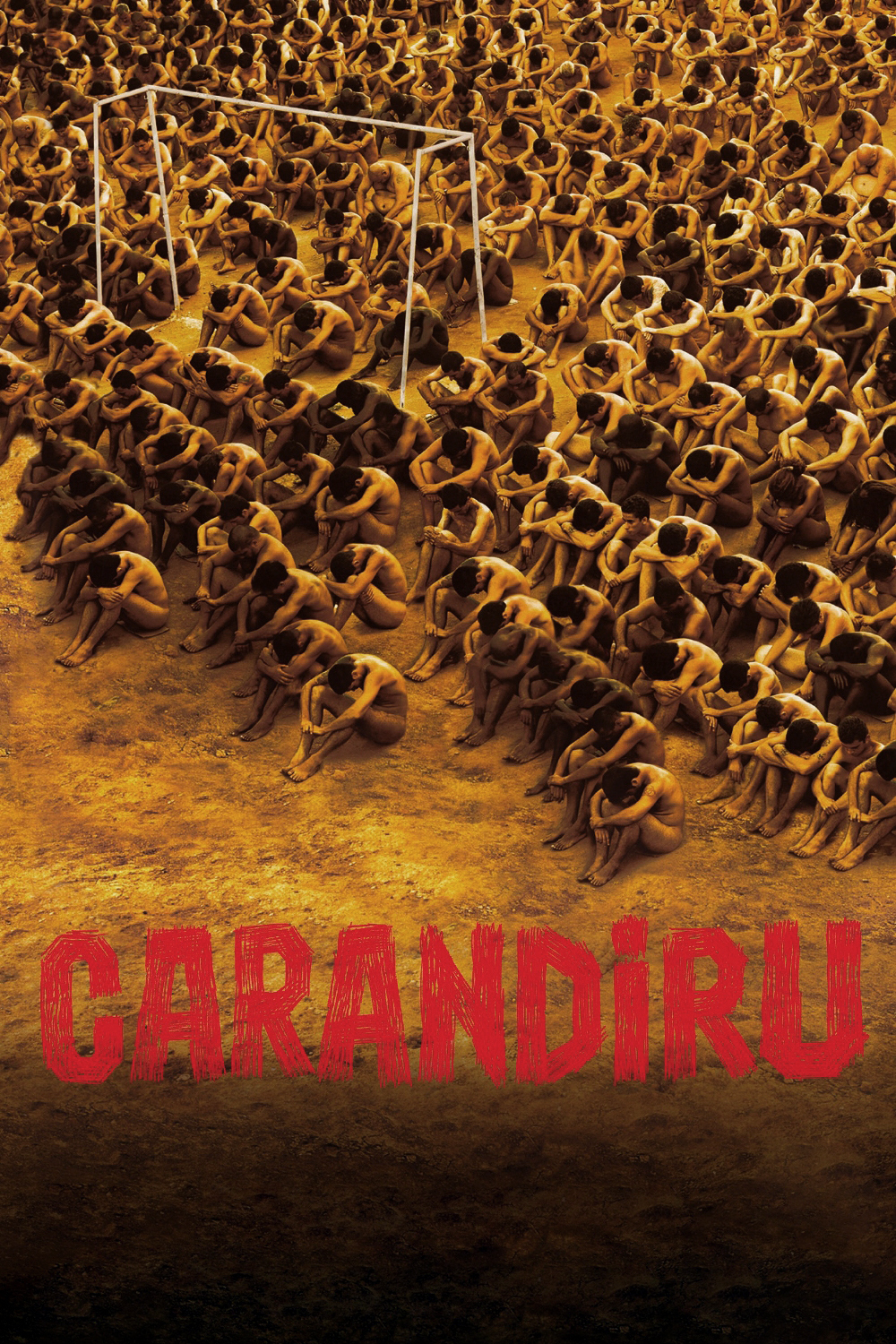

Hector Babenco’s “Carandiru” is a drama that adds a human dimension to that Dantean vision. Shot on location inside a notorious prison in Sao Paolo, it shows 8,000 men jammed into space meant for 4,000, and enforcing their own laws in a place their society has abandoned. The film, based on life, climaxes with a 1992 police attack on the prison during which 111 inmates were killed.

How this film came to be made is also a story. Babenco is the gifted director of “Pixote,” “Kiss Of The Spider Woman” and “At Play In The Fields Of The Lord.” An illness put him out of action for several years, and he credits his doctor, Drauzio Varella, with saving his life. As it happens, Varella was for years the physician on duty inside the prison, and his memoir, Carandiru Station, inspired Babenco to make this film, with Varella as his guide.

What we see at first looks like lawless anarchy. But as characters develop and social rules become clear, we see that the prisoners have imposed their own order in the absence of outside authority. The prison is run more or less by the prisoners, with the warden and guards looking on helplessly; stronger or more powerful prisoners decorate their cells like private rooms, while the weak are crammed in head to toe. Respected prisoners act as judges when crimes are committed. A code permits homosexuality but forbids rape. And the prison has such a liberal policy involving conjugal visits that a prisoner with two wives has to deal with both of them on the same day. Some prisoners continue to function as the heads of their families, advising their children, counseling their wives, approving marriages, managing the finances.

Dr. Varella, played in the film by Luiz Carlos Vasconcelos, originally went to Carandiru when AIDS was still a new disease; he lectures on the use of condoms, advises against sharing needles, but is in a society where one of his self-taught assistants sews up wounds without anesthetic or sanitation. The prisoners come to trust the doctor and confide in him, and as some of them tell their stories, the movie uses flashbacks to show what they did to earn their sentences.

In a prison filled with vivid, Dickensian characters, several stand out. There is, for example, the unlikely couple of Lady Di (Rodrigo Santoro), tall and muscular, and No Way (Gero Camilo), a stunted little man. They are the great loves of each other’s lives. Their marriage scene is an occasion for celebration in the prison, and later, when the police murder squads arrive, it is No Way, the husband, who fearlessly uses his little body to protect the great hulk of his frightened bride. Their story and several others are memorably told, although the film is a little too episodic and meandering.

There are weapons everywhere in the prison, but the doctor walks unarmed and without fear, because he is known and valued. The warden is not so trusted, and with good reason. After a prison soccer match ends in a fight that escalates into a protest, he stands in the courtyard, begs for a truce and asks the inmates to throw down their weapons. In an astonishing sequence, hundreds or even thousands of knives rain down from the cell windows. And then, when the prisoners are unarmed, the police attack.

The movie observes laconically that the police were “defending themselves,” even though 111 prisoners and no police were killed. The prison was finally closed in 2002, and the film’s last shot shows it being leveled by dynamite. Strange, how by then we have grown to respect some of the inmates and at least understand others. “Bus 174” is a reminder that although Carandiru has disappeared, prison conditions in Brazil continue to be inhuman.