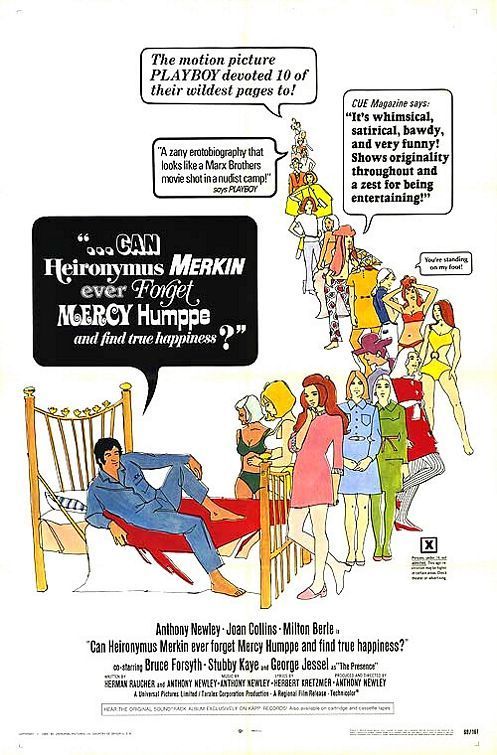

Large battles can be lost on small fields. One of the reasons so many fashionable New York critics didn’t like “Can Heironymus Merkin Ever Forget Mercy Humppe and Find True Happiness?,” I’m convinced, is that the title is so hard to fit into an opening paragraph.

Worse still, the film is critic-proof. It pretends not to be a movie at all, but a movie about the making of a movie. While Heironymus doggedly pushes ahead with his life’s story, he gets advice from all sides. Producers, writers and three particularly obnoxious critics are constantly popping up to tell us what’s wrong with the movie. It’s indulgently autobiographical. The pieces don’t fit together. It doesn’t have a proper ending. The Mercy Humppe sequence will never get past the little old ladies on the censor board. Right! Right!

But “Heironymus” isn’t as simple as that. It is strange, wonderful, original, and not quite successful. It is just about the first attempt in English to make the sort of personal film Fellini and Godard have been experimenting with in their very different ways. It is not as great as “8 1/2” but it has the same honesty and self-mocking quality.

It is about Anthony Newley, I suppose. He wrote and directed it, and plays Heironymus. He also plays the film’s director. But which film’s? There is, first of all, the film playing at the Playboy in Chicago: Heironymus 1, we’ll say. Then there’s the film Heironymus is showing to his mother, children and associates. It is an autobiographical account of his life: Heironymus II. Then there’s the film (within the film) being made about the night when Heironymus shows his film: Heironymus III. It’s the old barbershop mirror illusion: Reality fades into infinity, creating a great deal, of doubt along the way about what’s real.

Heironymus has arrived at the 40th year of his life. Studying insurance tables, he arrives at the gloomy conclusion that he has less time left than he’s already spent. He began life with two ambitions: to make it big in show business, and to make love to as many a woman as is humanly (and physically) possible. He was coached for the latter undertaking by the world’s prototype pimp, Good Time Eddie Filth. But even in the midst of revels planned by Eddie, he receives disturbing visits from an old man dressed in white: The Presence. The Presence smokes his cigar, tells lousy anecdotes without a point, and waits around, so it seems, until Heironymus dies.

Famous and rich, and surrounded by women, Heironymus still seeks happiness. He finds it, or thinks he does, with the virginal Mercy Humppe. But Mercy is too good, too pure; he returns to the arms of Good Time Eddie Filth’s girls. Thus he ends as he began, seeking happiness everywhere except where he finds it.

Newley has conceived his film in surrealistic terms. Most of the action takes place on a seashore somewhere where Heironymus has piled up exhibits for a museum history of his life. Episodes are staged in the form of music-hall revues, all tied together by the device of Heironymus’ autobiographical project. There are interruptions, financial crises, halts while the writers create new dialog. And eventually out of the chaos emerges . . . well, a chaotic movie, in which nothing fits together, which doesn’t have a proper ending, is indulgently autobiographical and all that.

But what also emerges, on reflection, is a movie that sags under the weight of too much invention, rather than too little. The miracle is that Newley is able to keep all the pieces somehow related, and to get them to add up to a statement, or at least a feeling, about the nature of life. The result may be more of a juggling feat than a directorial triumph, but it’s a good act while it’s onstage.