When William Andrews (Fred Hechinger) first enters the secluded yet bustling Kansas outpost of Butcher’s Crossing, he is bright-eyed and adventurous. Like many men his age, particularly men of the film’s 1874 setting, he has taken Horace Greeley’s phrase “Go West, young man” as gospel. Against his Bostonian father’s wishes, William is taking a break from Harvard in the hopes of working for McDonald’s (Paul Raci) buffalo hunting outfit. William believes the rugged work on a rugged landscape will give him a real-world education. It’s a tantalizing thought whose fulfillment should make for an invigorating Western.

And yet, the results are far from those prospects. “Butcher’s Crossing” is unfocused, distant, and flat.

Adapted from John Edward Williams’ same-titled novel, director Gabe Polsky’s film is a conservationist narrative about man’s greed and tyranny over nature. While the Western genre has always been a handy tool for mythologizing, it can equally serve as a site to retrace past cultural wrongs (a turn Martin Scorsese attempts with “Killers of the Flower Moon,” for example). Through Williams’ impressionable eyes, Polsky aims to connect the historical near-extinction of the buffalo to a modern audience anxious about the present wave of human-influenced extinctions happening today. It’s an admirable desire that never evolves beyond basic aspirations.

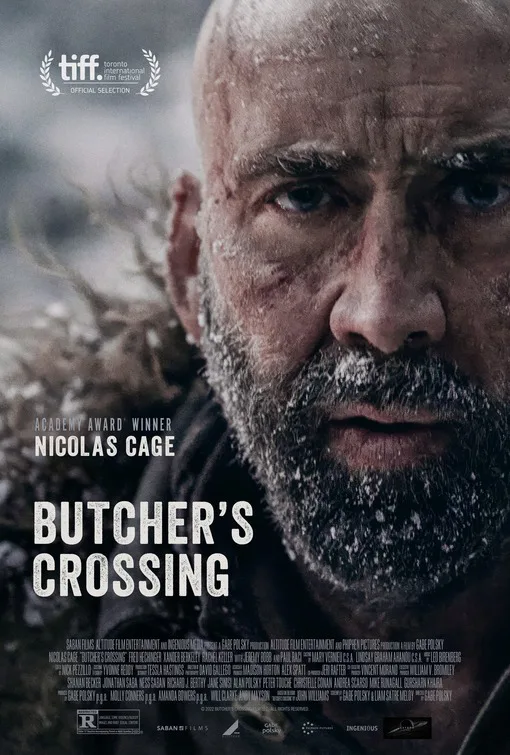

When William approaches McDonald for a job, he rebukes the young man. McDonald wants to spare William from this soul-crushing trade. But William also hears about Miller (a misplaced Nicolas Cage), an accomplished hunter sporting a deep black beard, a shaved head, and a seemingly impossible dream: Nearly a decade ago, he saw a valley in the Colorado Territory chock full of buffalo. With the animal now scarce around Kansas, Miller’s vision is alluring to William. Miller just needs $500 to hire enough men—like the prickish Fred (Jeremy Bobb) and the superstitious Charlie (Xander Berkeley)—to make the expedition work. And as luck would have it, William has about $500 burning a hole in his pocket. The question, of course, is whether he can trust Miller?

Due to the film’s curt passage of time, you continually feel that Polsky is operating with less-than-ideal constraints; the 107 minutes dedicated to the story fall woefully short of accommodating the director’s desires. The trek to Miller’s buffalo oasis is an arduous one. And yet, other than a couple of stops along the way—where young William sees how no one can be trusted—the psychological implications of wandering a vast desert expanse without water are summed up through a dreadfully edited fever dream experienced by a dehydrated William.

Though Hechinger does exceptional physical work to push down his character’s boyish bounce, Polsky becomes bored with the character. Upon arriving in the Colorado territory, the lens quickly switches to Miller. At first, William marvels at Miller’s hunting ability; he experiences unbridled joy when Miller helps with his first buffalo kill. But Miller isn’t merely here to hunt what he needs; he wants to wipe out the whole herd. What follows is a massacre, a bloodbath that disgusts the other hunters and pushes William to perpetual bouts of vomiting. The film becomes enamored with Cage during these sequences. But apart from Cage’s prototypical slide into the sinister, very little is communicated about the internal workings of Miller.

For a film attempting some psychological drama, it struggles to connect the mindset of these men with their harsh environment. The inarticulate visual language becomes glaringly obvious when “Butcher’s Crossing” becomes a snow Western version of “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre.” Unlike John Huston’s picture, madness and greed are merely affectations here rather than fully felt motivations pushing these characters. Worse yet, you’d think the isolation of these men being trapped in this valley for months would take up more time. But again, Polsky speeds ahead using more unwieldy fever dream montages to do the heavy lifting.

We don’t get the necessary edge for the hellish carnage the director wants to capture until the final freakout. But by the time it arrives, William is riding away, and the credits are rolling. We know he has changed; manifest destiny isn’t a grand adventure. And yet, what did he find? We’re led to believe it was a newfound respect for nature. But apart from Polsky filming in the striking hills of the Blackfeet Reservation in Montana, nature never becomes a main character. It remains in the background to witness Williams’ crumbling psyche and his rising guilt but is too distant to give their relationship life. Instead, disappointingly, “Butcher’s Crossing” languishes under man’s folly.

Now playing in theaters.