One of the most sensible suggestions I’ve heard about telepathy is that the human race probably evolved out of it. It was necessary for us to lose the power of telepathy in order to become individuals. If we could tap into the Racial Mind all the time, think of the trouble if the guy next door had a headache.

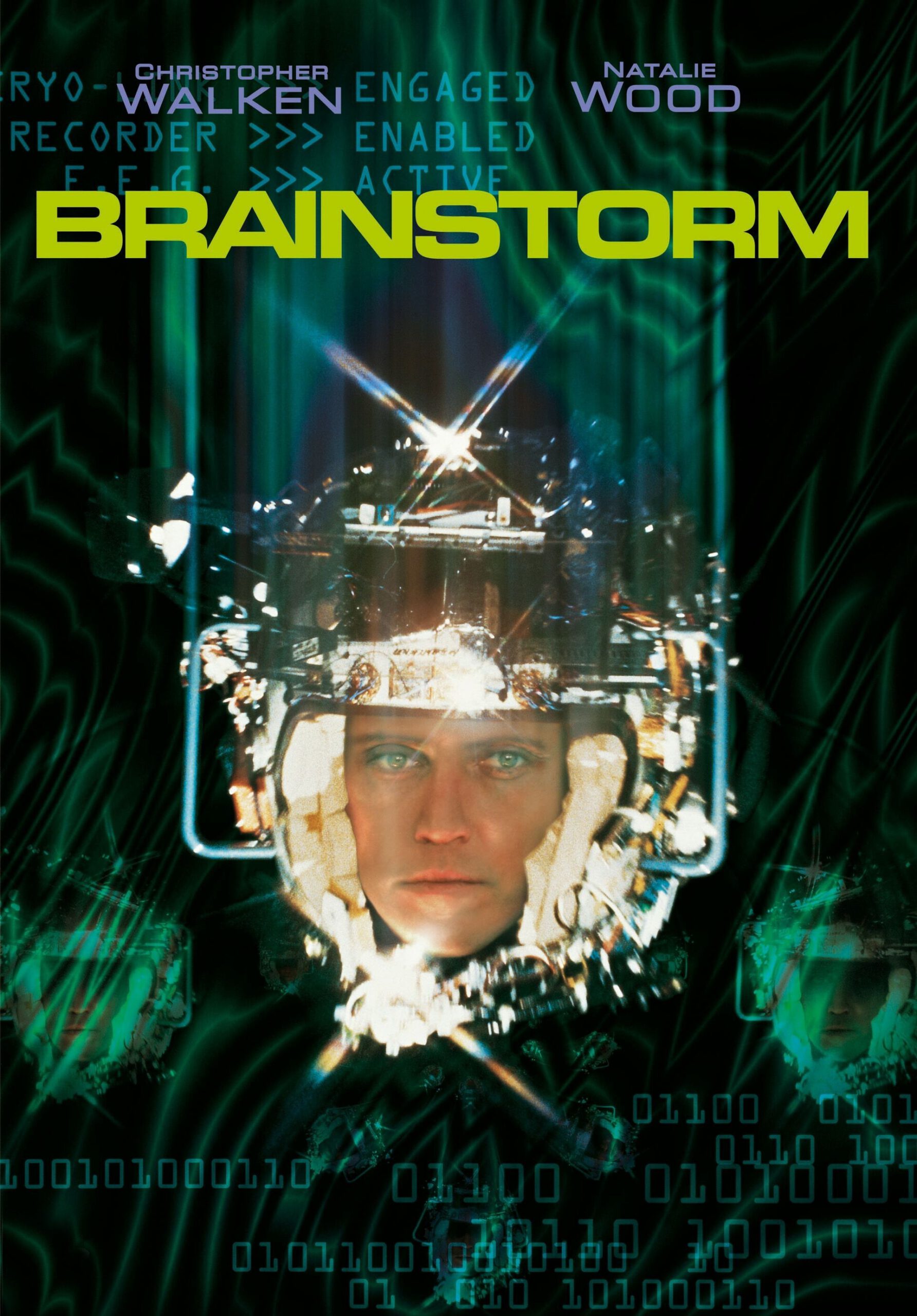

“Brainstorm” considers problems like that. It begins with the invention of an amazing machine that gives you the impression you are actually having somebody else’s experience. Plug into it, and you hear, see, feel, touch and smell whatever’s been programmed. What’s more, it’s telepathic; it can take those sensations out of one mind and channel them into another.

The applications are endless. In one demonstration, the wearer believes he is being chased down a mountain road by a runaway truck, and then his car misses a curve and goes sailing through the air. There also are the usual stunts like putting you in the front seat of a roller coaster. But then there’s a complication. One of the scientists who developed the gadget inadvertently records her own death. And when her colleagues play back her recording, they have the death experience, too.

This is a good idea for a movie. Unfortunately, in “Brainstorm” it remains basically an idea. The characters take such a secondary importance to the gadget that we never feel much for them. Ironic, that the movie doesn’t give us their sights, smells, tastes, etc. The cast is populated with actors whose full abilities aren’t used. We particularly notice that in the case of Natalie Wood, who died while making this movie, and who is good to see once again, but who isn’t given even one big, challenging, deep scene; she’s just part of the plot machinery.

Louise Fletcher is also misused. She plays a chain-smoking scientist. Period. She smokes all of the time. She lights a cigarette every time the camera looks at her. Half of this mannerism would have been sufficient; it becomes a joke instead of a trait. Cliff Robertson and Christopher Walken, as the head of the computer company and his brilliant scientist, also are trapped in roles rather than characters.

But the technical effects are intriguing. Douglas Trumbull, the director, is Hollywood’s legendary special effects ace (“2001: A Space Odyssey,” “Silent Running,” “Close Encounters of the Third Kind“), and he does a wonderful job of making the telepathic experiences visually exciting. He cuts back and forth between wide screen and regular format, between ordinary sound and stereo, between standard lenses and astonishing visual effects. Great, except the people get overlooked.