When Lee Atwater was a boy, a fryer full of hot grease fell on his little brother Joe, killing him. “He said he heard those screams every single day for the rest of his life,” a friend remembers. “He grew up in a world without mercy.”

A plausible case can be made that Lee Atwater was the greatest single influence on American politics in the last 40 years. He was instrumental in the elections of Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush. Karl Rove and Bush 43 were his proteges. It is universally acknowledged that Atwater wrote the modern Republican playbook. “If he had lived,” a friend believes, “Bill Clinton would never have been elected president.”

Atwater predicted before anyone else that Clinton would be the greatest threat to Bush 41. He took the Clintons’ Whitewater investment, in which they lost their entire $28,000, and made it the target of a $70 million federal investigation, which produced little of interest except a campaign talking point.

The funny thing was, Atwater didn’t much care if he was a Republican or a Democrat. It was only about winning. Looking for opportunities in college, he picked the Young Republicans because there were fewer of them and better opportunities for him. Ever since he managed a campaign for class president in high school, he found himself more at home behind the scenes. In the Young Republicans, he managed Karl Rove’s campaign to lead the organization. Members of the YRs at the time believe Rove probably lost, but say Atwater stole the election and then placed the decision into the hands of Vice President George H.W. Bush, who decided in favor of Rove.

Soon he was inside the Republican national party. Having helped Reagan survive Iran-contra, he more or less appointed himself Bush 41’s campaign adviser. He created the infamous Willie Horton ads when Bush ran against Michael Dukakis, and floated rumors that Dukakis was against the Pledge of Allegiance. Asked at the time about the labeling of Dukakis as unpatriotic, young Bush 43 said to call him that would be a “mis-adjective.”

Even while running Bush 41’s campaign, he was never admitted to the Bush inner circle, Barbara Bush distrusted him, and he came close to being fired. Then Bush started winning primaries. Remembering that presidential year, the Republican strategist Mary Matalin says, “Bush was a wimp and a wuss. Atwater was a hick and a hack.” Atwater perfected at that time the technique of the “push-pull” poll, where the question itself served to spread suspicion (“do you believe Governor Dukakas opposes saluting the flag?”). He and George W. Bush became fast friends soon after they met, Rove adopted his tactics, and Atwater’s posthumous influence could be seen in the Swift-Boating of John Kerry.

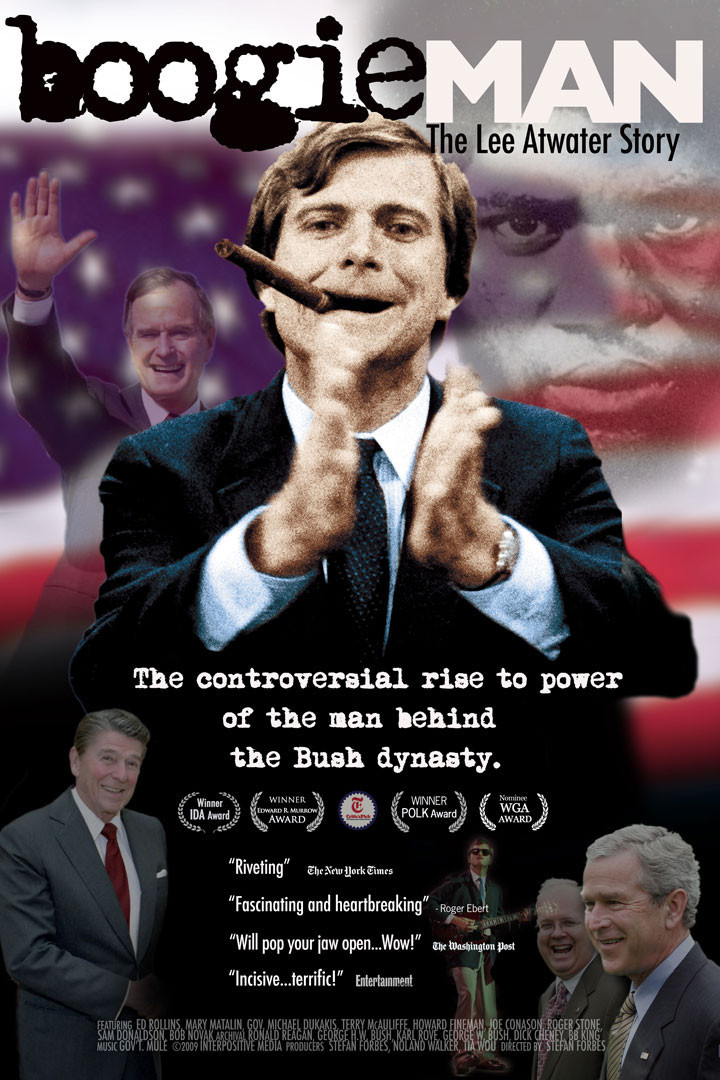

“Boogie Man: The Lee Atwater Story,” a remarkable documentary directed by Stefan Forbes, uses interviews with Atwater’s targets and, especially, his old comrades, to paint a remarkable portrait of Atwater, who was charming, funny, smart and a good enough blues musician to play on David Letterman and cut an album with B.B. King. He was also tortured and driven, and a bi-partisan backstabber. Ed Rollins, Atwater’s White House boss at the time, says in the doc that Atwater leaked a false story to ABC that “top GOP sources” said Rollins was leading an undercover effort to smear Geraldine Ferraro. Atwater wanted to force Rollins out in a new Bush administration, he says. Rollins hated him. But when Atwater was dying, he begged Rollins to look after him. “They’re trying to destroy me,” he said.

Atwater was popular with many reporters because he was good for quotes and leaks (or “leaks”) and denials that were outrageous but delivered with disarming charm. About Iran-contra: “We don’t discuss how we make sausage.” About the Willie Horton ad: “I don’t think a lot of Southerners even noticed there was a black man in that ad.” Atwater had a genius for creating language that voters would remember. Learning that Tom Turnipseed, a Democratic opponent to his South Carolina congressional candidate, had received shock therapy as a young man, Atwater gleefully translated: “They had to hook him up to jumper cables.”

“Boogie Man” is a fascinating portrait of an almost likable rogue. You’d rather spend time with him than a lot of more upstanding citizens. It makes a companion piece to Oliver Stone’s “W.”

Atwater’s death by brain tumor at age 40 was preceded by deathbed regrets. The film has heartbreaking footage of this boyishly handsome man turned by chemo and radiation into a feeble, bloated caricature of himself. On his deathbed, he called for a Bible, and sent telegrams of apology to those he had offended, even Willie Horton. “He said what he had done was bad and wrong,” Rollins remembers. “He was scared to death of the afterlife.”

Mary Matalin, who never trusted or approved of Atwater, says: “After he died, they found the Bible still wrapped in its cellophane.” She thinks he might have been spinning right to the end.

Unusually for a South Carolina boy, Atwater had absolutely no interest in sports. None, except for professional wrestling. He loved it because it was fake, and everyone knew it was fake, and that was the whole point.