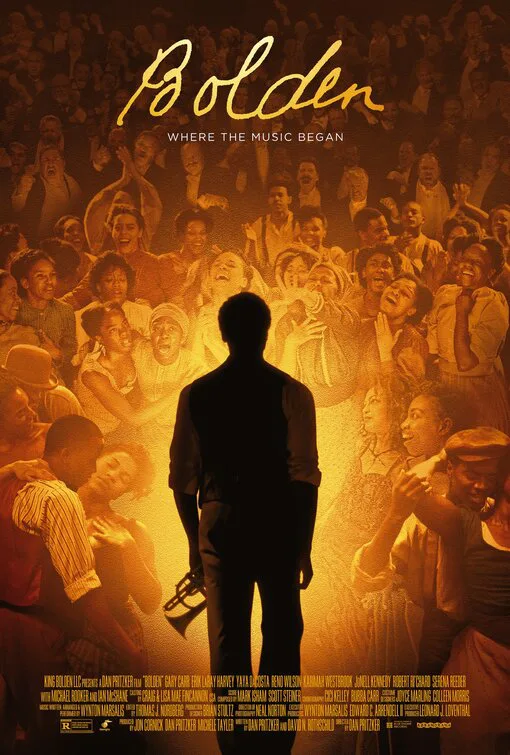

Not much is known about Buddy Bolden, the legendary cornetists Dan Pritzker’s film credits as the inventor of jazz. It’s not much to go on for a movie, but Pritzker takes some creative liberties with those blank pages in history and fills them with an impressionistic rendering of the man’s life. The result is sometimes dizzying, enchanting or confounding, but it is certainly never boring.

“Bolden” is rather different than your standard-issue biopic. No scene takes up the screen too long before something else takes its place. Flashing between the hazy memories and fever dreams, “Bolden” flits across Buddy’s life with no discernable rhythm. At other points in the movie, other people tell his story, as was the case when he became mentally ill and ended up in an institution. It’s hard to get a sense of the man in the middle of all this noise.

After his birth in New Orleans in 1877, the movie breezes through Bolden’s memories of watching his mother work on clothes, playing freestyle jazz with his band, breaking into the rowdy night club scene and falling in love. Then there’s the downward spiral of drugs, health issues and cheating on that love of his life. The scenes are almost always accompanied by music and dancers, like a song-filled version of Bob Fosse’s “All That Jazz.” These scenes intertwine and interchange freely, perhaps as a nod to the free-flowing style of jazz music itself.

Like Roy Scheider in “All That Jazz,” Gary Carr must hit the right notes as Bolden at his highest and lowest spirits. This ranges from his first signs of losing control while in concert, putting on the charms to win over a girl or being so out of it, he wanders the frame like a zombie. He’s electric on stage, which makes the scenes where he’s out of it or about to lose control so much vicious. In a surprising cameo, Ian McShane shows up as a racist judge who spouts hateful things at Bolden in his office like a slimier version of Leonardo DiCaprio’s character in “Django Unchained.”

There’s not much of consistency in terms of Neal Norton’s cinematography, but that helps the audience keep track of which timeline have Bolden’s memories have jumped to next. The ones of his childhood and early career are either faded grey or sepia, depending on the scene. For instance, the wooden building where Bolden’s mother works feels warm from the reddish brown floorboards. The movie uses varying degrees of soft focus, but this instance is one of the heaviest examples as if this were one of his happiest, purest memories. Then, as the song ramps up, the extras begin to move less like worker bees and more like a corp de ballet. Toe shoes appear out of nowhere, and the memory becomes a light fantasy, an escape for the sadness still to come.

Stitching together these vignettes are dreary interstitial scenes of Bolden locked up in a mental institution. They are cloaked in dingy green and black, interrupting the flow of the brighter colors of happier memories. Bolden’s nostalgic trip is in part caused by listening to Louis Armstrong play on the radio. He wanders the halls in a daze, still half-heartedly looking for an escape. It’s as if he still had music left to play. The scenes with Armstrong playing in front of a segregated white audience while his Black fans listening outside is perhaps the most vibrant moments in the movie. It’s the kind of future that Bolden never got to enjoy in his lifetime.

There are times when the movie feels like it’s trying too hard to be capital-A Art. The quasi-experimental loose narrative can be distracting when you’re still trying to figure out the layout of Bolden’s life. There a handful of scenes of nude black women, often playing prostitutes, that I’m not sure adds much to the story apart from forcing in sex appeal in a tragic story. There’s another inexplicable insert of a shot of a group of black women holding babies when Bolden seems to freak out over the news of his impending child. Aside from the visual shock, does it even mean anything at all to Bolden’s story?

“Bolden,” as with Pritzker’s previous jazz-related film, “Louis,” feel like the works of a jazz fan who wants to share his admiration of this art with a new audience. Bringing light to Bolden’s story is one thing, but to pull off a non-linear retelling of a man’s life through the few known fragments of his story is a different kind of challenge. Yet, the film is always lively, on the move with a jazz or ragtime beat and ensemble cast to follow. This unconventional riff on a legendary figure may distance some and will likely connect with others. Which, I guess you could say is not unlike improvisational jazz itself.