“Boiler Room” tells the story of a 19-year-old named Seth who makes a nice income running an illegal casino in his apartment. His dad, a judge, finds out about it and raises holy hell. So the kid gets a daytime job as a broker with a Long Island, N.Y., bucket shop that sells worthless or dubious stock with high-pressure telephone tactics. When he was running his casino, Seth muses, at least he was providing a product that his customers wanted.

The movie is the writing and directing debut of Ben Younger, a 29-year-old who says he interviewed a lot of brokers while writing the screenplay. I believe him. The movie hums with authenticity, and knows a lot about the cultlike power of a company that promises to turn its trainees into millionaires, and certainly turns them into efficient phone salesmen.

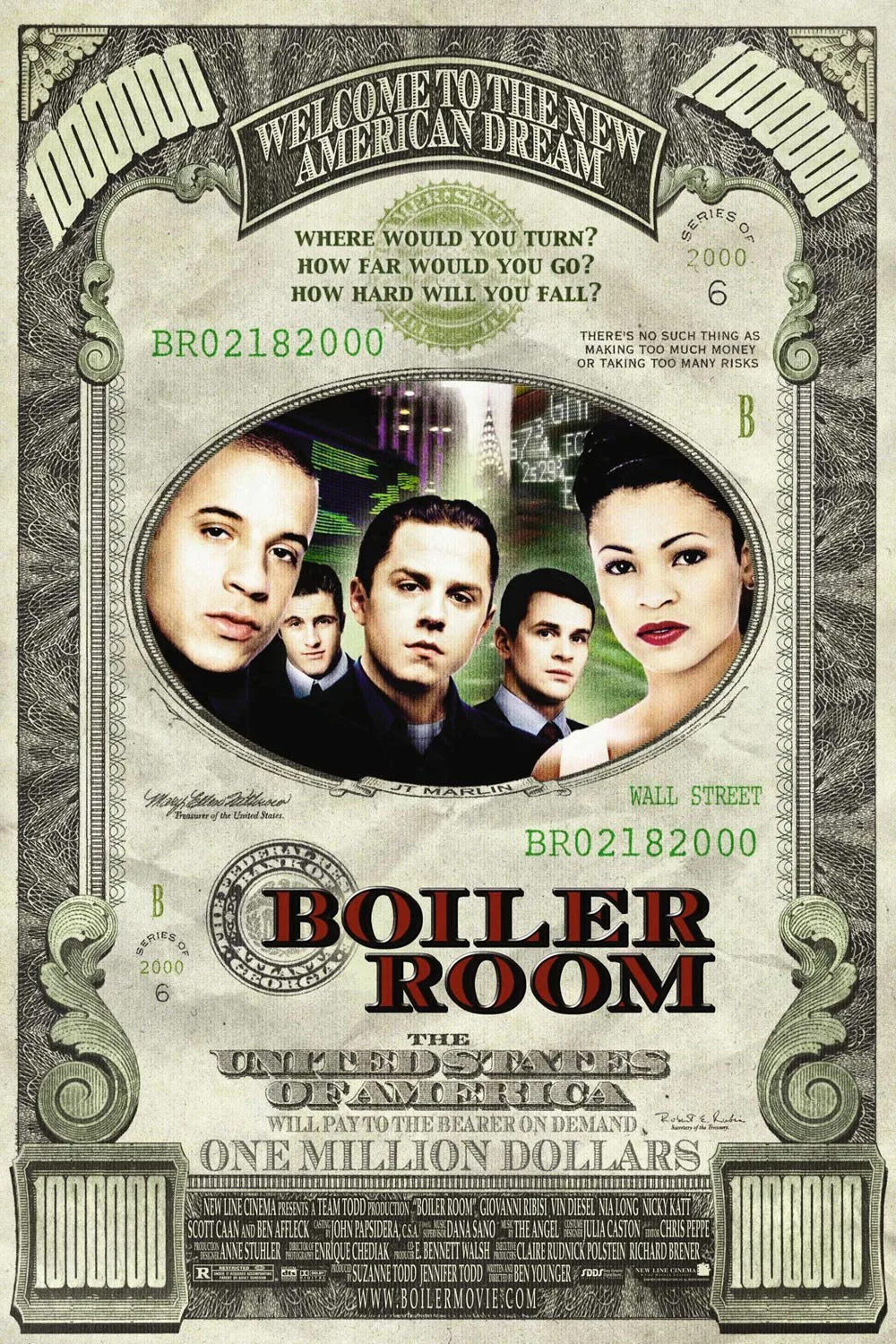

No experience is necessary at J.T. Marlin: “We don’t hire brokers here–we train new ones,” snarls Jim (Ben Affleck), already a millionaire, who gives new recruits a hard-edged introductory lecture crammed with obscenities and challenges to their manhood. “Did you see `Glengarry Glen Ross’?” he asks them. He certainly has. Mamet’s portrait of high-pressure real estate salesmen is like a bible in this culture, and a guy like Jim doesn’t see the message, only the style. (Younger himself observes that Jim, giving his savage pep talks, not only learned his style from Alec Baldwin’s scenes in “Glengarry” but wants to be Baldwin.) The film’s narrator is Seth Davis (Giovanni Ribisi), an unprepossessing young man with a bad suit who learns in a short time to separate suckers from their money with telephone fantasies about hot stocks and IPOs. Everybody wants to be a millionaire right now, he observes. Ironically, the dream of wealth he’s selling with his cold calls is the same one J.T. Marlin is selling him.

In the phone war room with Seth are several other brokers, including the successful Chris (Vin Diesel) and Greg (Nicky Katt), who exchange anti-Jewish and Italian slurs almost as if it’s expected of them. At night the guys go out, get drunk and sometimes get in fights with brokers from other houses. The kids gambling in Seth’s apartment were better behaved. We observe that both gamblers and stockbrokers bet their money on a future outcome, but as a gambler you pay the house nut, while as a broker you collect the house nut. Professional gamblers claim they do not depend on luck but on an understanding of the odds and prudent money management. Investors believe much the same thing. Of course, nobody ever claims luck has nothing to do with it unless luck has something to do with it.

The movie has the high-octane feel of real life, closely observed. It’s made more interesting because Seth isn’t a slickster like Michael Douglas or Charlie Sheen in “Wall Street” (a movie these guys know by heart), but an uncertain, untested young man who stands in the shadow of his father the judge (Ron Rifkin) who, he thinks, is always judging him.

The tension between Seth and the judge is one of the best things in the film–especially in Rifkin’s quiet, clear power in scenes where he lays down the law. When Seth refers to their relationship, his dad says: “Relationship? What relationship? I’m not your girlfriend. Relationships are your mother’s shtick. I’m your father.” A relationship does grow in the film, however, between Seth and Abby (Nia Long), the receptionist, and although it eventually has a lot to do with the plot, what I admired was the way Younger writes their scenes so that they actually share hopes, dreams, backgrounds and insecurities instead of falling into automatic movie passion. When she touches his hand, it is at the end of a scene during which she empathizes with him.

Because of the routine racism at the firm, Seth observes it must not be a comfortable place for a black woman to work. Abby points out she makes $80,000 a year and is supporting a sick mother. Case closed, with no long anguished dramaturgy over interracial dating; they like each other and have evolved beyond racial walls. Younger’s handling of their scenes shames movies where the woman exists only to be the other person in the sex scene.

The acting is good all around. A few days ago I saw Vin Diesel as a vicious prisoner in the space opera “Pitch Black,” and now here he is, still tough, still with the shaved head, but now the only guy at the brokerage that Seth really likes, and trusts enough to appeal to. Diesel is interesting. Something will come of him.

“Boiler Room” isn’t perfect. The film’s ending is a little too busy; it’s too contrived the way Abby doesn’t tell Seth something he needs to know; there’s a scene where a man calls her by name and Seth leaps to a conclusion when in fact that man would have every reason to know her name; and I am still not sure exactly what kind of a deal Seth was trying to talk his father into in their crucial evening meeting. But those are all thoughts I had afterward. During the movie I was wound up with tension and involvement, all the more so because the characters are all complex and guilty, the good as well as the bad, and we can understand why everyone in the movie does what they do. Would we? Depends.