Bobby Sands and nine other men—all prisoners at the infamous “H-Block” in Northern Ireland—starved themselves to death over the course of almost six months, in protest of the British government refusing political prisoner status to those who had been incarcerated for actions associated with the Provisional Irish Republican Army. Sands was the first to participate in the 1981 hunger strike and the first to die after a long, painful biological process that would leave him blind, unable to be touched by even blankets, and a mere skeleton of a man. He was 27 at the time of his death, after spending the majority of his adult life imprisoned in the same location.

There isn’t, then, much to say about Sands’ life, apart from those nine years in which he was imprisoned, awaiting imprisonment, or engaged in activity that would lead to his imprisonment. The talking heads in “Bobby Sands: 66 Days” argue that this made Sands the ideal candidate for his eventual martyrdom.

There weren’t many stories about his personal life, other than the fact that his family had to flee their hometown from the violence of Protestant unionists, whose prejudice against the minority Catholic population merged with their political belief that Northern Ireland should remain part of the United Kingdom. During his second term of incarceration, he was married and had a son, although the worst that could be said of his role as a husband and a father was that he was an Irish republican above all else—a point that just happened to make for a good argument about the sincerity and passion of his political beliefs.

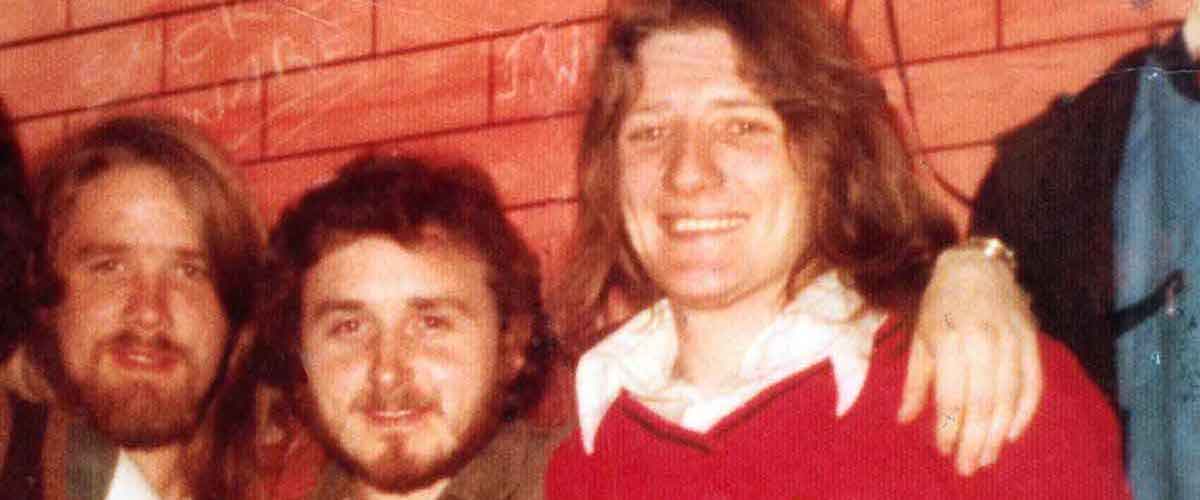

There weren’t even many photos of Sands, which made it easy for the higher-ups of the IRA to find a suitable one to use in a campaign for Sands to fill a seat in the House of Commons that needed to be filled after the sudden death of a Member of Parliament—shortly after Sands began his hunger strike. In the photo, he is smiling and surrounded by fellow inmates at the internment camp where he served his first prison sentence. Someone else in the photo says that they were particularly happy that day because someone in the camp had brewed some makeshift beer.

With this documentary, director Brendan Byrne doesn’t try to find the man behind the iconic figure so much as attempt to uncover the reasons Sands became an icon. The movie is part history lesson, part cultural examination, and part biography. The biographical element comes up short, although Byrne’s point is that the first two elements explain why that is. Sands was a man almost exclusively defined by the history and culture of the people for whom he believed he was fighting and, later, dying. The excerpts of Sands’ prison diary that are quoted—and at times animated—only mention his family once. Sands writes that he knows he is breaking his mother’s heart by electing to participate in the strike.

Otherwise, Sands’ writing is exclusively political. Byrne follows suit by populating the movie with an assortment of historians, experts (from former IRA members to a medical professional who focuses on starvation), and politicians. It’s one of those documentaries in which the central arguments seem happened-upon—almost as if by chance—by the observations and opinions of the talking heads within it.

In other words, the impact of the movie comes in spurts, connected to a few keen insights from this historian or that expert. Of particular intrigue, for example, is a brief dissection of the use of hunger strikes in Irish—and especially Irish republican—history, as well as how the means of protest ties into religion (no one denies intentionally connecting Sands’ suffering to that of Jesus) and a philosophy of conflict. Along with the other detainees at the internment camp, Sands read works from an assortment of revolutionaries. One of the main takeaways was the rationale for the two prison hunger strikes, the first of which a year prior failed to have any effect: War is not won by inflicting suffering but by displaying one’s ability to survive inflicted suffering.

The contradiction, of course, is the death toll, with a significant number of civilians, caused by the Provisional IRA during the Troubles. It’s a contradiction that Byrne acknowledges with numbers and, perhaps, the hope that enough time has passed for it to be a matter of historical fact without any moral reckoning.

The moral stance, of course, was the one promoted by the British government, led at the time by Margaret Thatcher, who took a hardline stance against offering any concessions to Sands and his fellow inmates. The ways Thatcher and her administration navigated the international attention Sands’ strike brought to the cause of Irish nationalism are fascinating here, if only because the government essentially used the same tactic the IRA used in regards to Sands.

The government dehumanized him, as a criminal—and only a criminal—deserving of punishment, in order to undermine sympathy for him and his cause (the government’s reaction as the strikers die is a heartless piece of political strategy); the IRA dehumanized Sands to turn him into a symbol. For its own part, “Bobby Sands: 66 Days” doesn’t reclaim its subject’s humanity.