Note: The following was reworked from a blog post that Roger Ebert filed from the 2012 Toronto Film Festival. In late March, he requested that it be refashioned into a review because he was not feeling well enough to write one from scratch. “Blancanieves” was one of 12 films invited to this year’s Ebertfest, and Roger was one of the movie’s biggest champions. As director Pablo Berger urged Ebertfest attendees, “If you like this film, spread the word, in honor of Roger.” — Laura Emerick

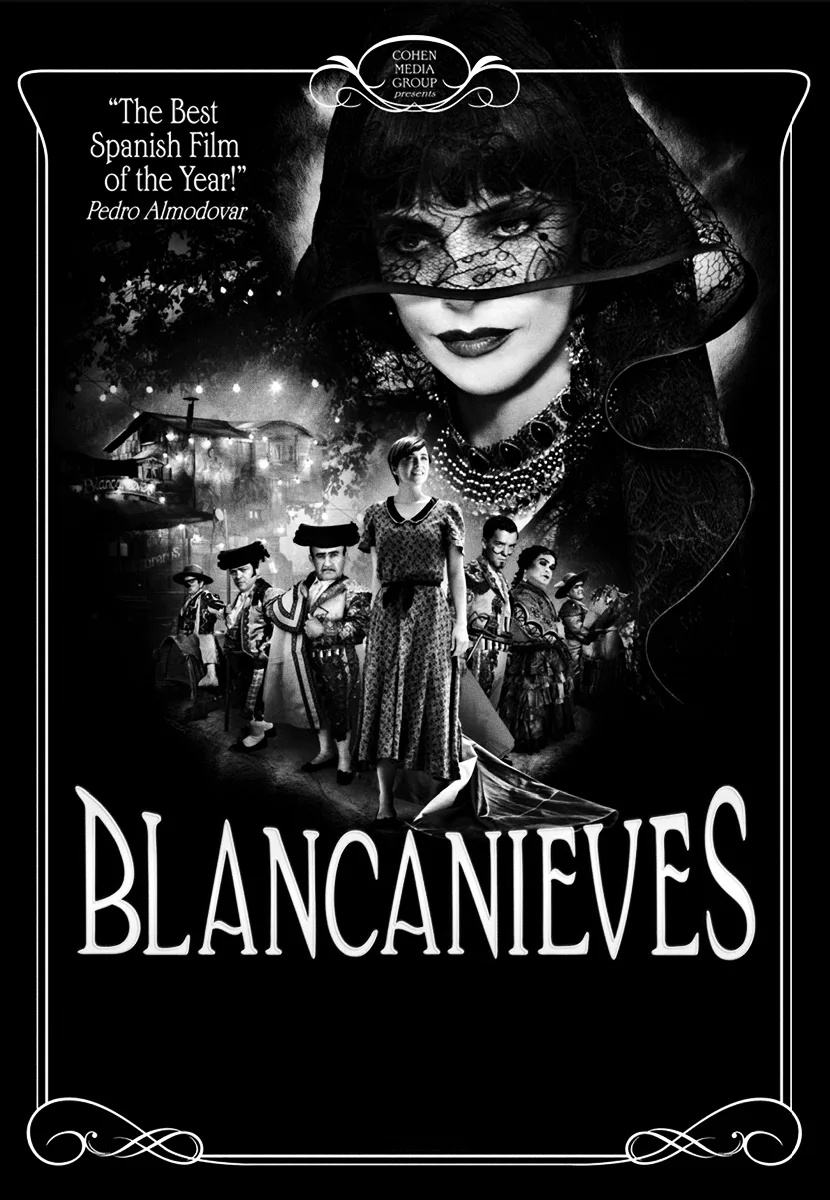

It’s too soon to declare a trend, but a silent film once again seems likely to become a success in the contemporary film world: “Blancanieves,” a striking, visually stunning Spanish feature, written and directed by Pablo Berger.

Although the story draws on the Brothers Grimm and the legend of Snow White, it is anything but a children’s movie. It is a full-bodied silent film of the sort that might have been made by the greatest directors of the 1920s, if such details as the kinky sadomasochism of this film’s evil stepmother could have been slipped past the censors.

The delightful “The Artist,” which slipped away with last year’s Academy Award for best picture, cheated a little by having tongue-in-cheek fun with its silence, and even allowing a few words to sneak in. “Blancanieves” exploits the silent medium for its strengths, including the fact that it can so easily deal with fantasy. This is as exciting, in many of the same ways, as the greatest traditional silent masterpieces by Dreyer, Pabst or Murnau. It’s a Spanish film, but of course silent films speak an international language.

The story opens with a famous matador, Antonio Villalta (Daniel Giménez Cacho), who is filled with swaggering ego. All goes wrong for him. He is paralyzed in the ring, and his beloved wife dies in childbirth. Their daughter, Carmen, is raised by her grandmother until her death. Antonio unwisely marries the heartless Encarna (Maribel Verdu), his former nurse, who wants only his money and ignores him as he sits in a wheelchair in his room.

After Carmen is orphaned, Encarna allows the child to come and live with her and her father, only to give her a room in the barn and put her to work at hard labor. Encarna, meanwhile, dominates the household’s chauffeur in classic boot-and-whip style. Eventually, Carmen manages to sneak into the mansion and bond with her father, who teaches her the art of bullfighting.

Fed up with caring for her invalid husband, Encarna hastens his demise. She also orders the chauffeur to eliminate the now-teenage Carmen.

Left for dead in a nearby river, Carmen is discovered by a troupe of dwarves, Los Enanitos Toreros. They are bullfighters who travel between cities and look like characters out of a Tod Browning film. They name her Blancanieves, Spanish for Snow White.

When one of them is wounded, she leaps into the ring and distracts the bull, using the matador skills she learned from her father. Eventually she, too, becomes a famed matador.

This film is a wonderment, urged along by a full-throated romantic score. Carmen as a child is performed lovably by the angelic Sofía Oria and as an adult, Macarena García. As with “The Artist,” I believe audiences will discover they like silent films more than they think they do. The silents offer experiences and dimensions different from talking pictures.