Anna is a privileged and happy child until one day her parents radically change their style of living. This does not suit her. Like all children, she is profoundly conservative — not in a political way, but by demanding continuity and predictability in her life. One day she lives in a big house with a lovely garden, and the next she and her little brother are suddenly yanked into a grotty flat filled with bearded, chain-smoking young men.

It is 1970, in Paris, at a time of social change. What has happened is that her middle-class parents have become radicalized. Her Spanish father Fernando (Stefano Accorsi) sufferers from guilt because his family cooperates with Franco’s fascist regime, but his sister and her husband are communists. After the husband is arrested and destined to who knows what terrors from the police, Fernando and his French wife Marie (Julie Depardieu) go to Spain, help his sister and niece escape and come home as left-wing activists. Their idealism causes them to move into more humble working-class quarters and join forces with a group of Chilean exiles working for the election of the reformer Salvador Allende.

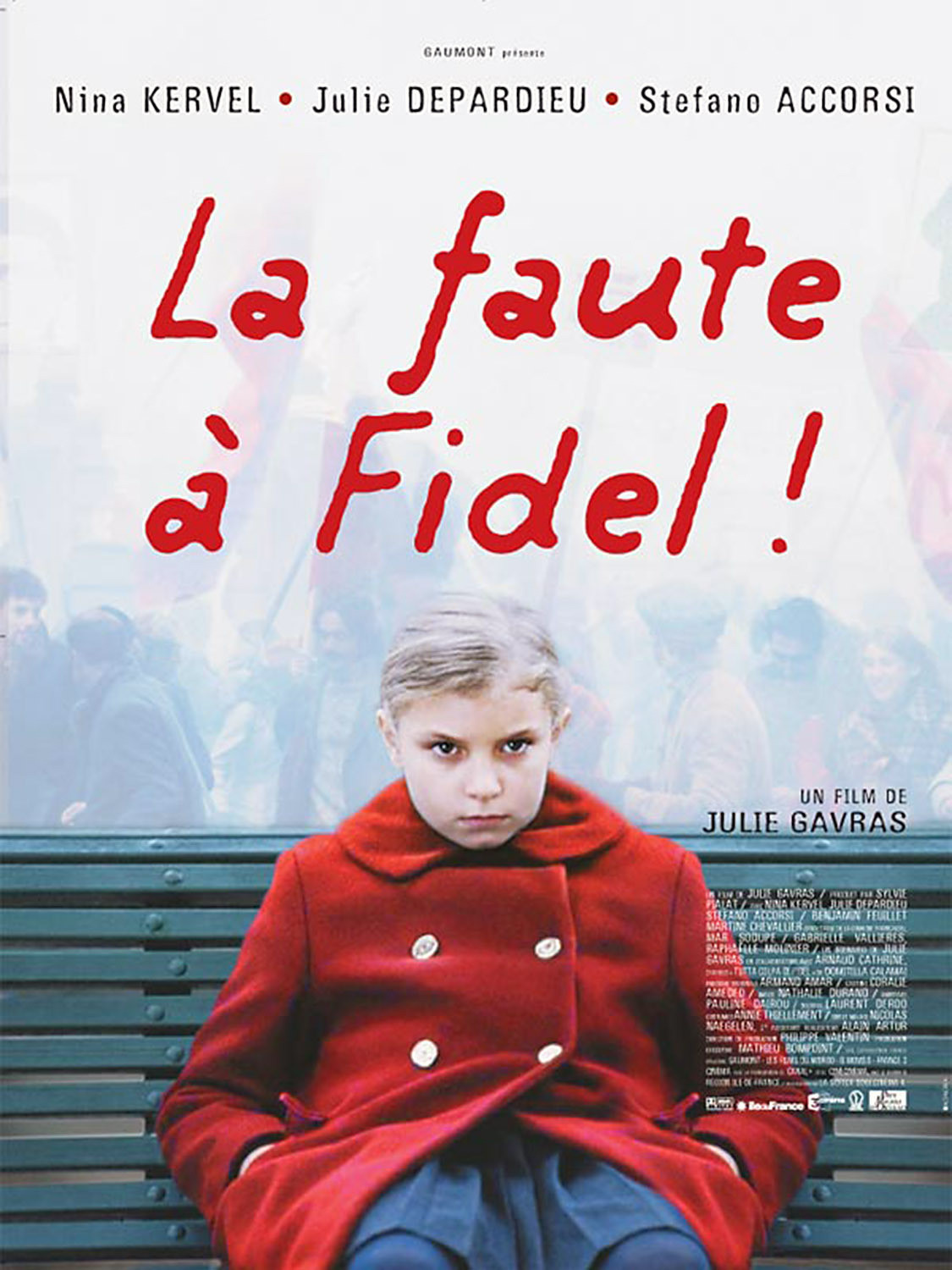

Anna (Nina Kervel) understands all of this only dimly. What she knows is that her world is out of order and her parents are acting oddly. She loves going to a Catholic school, but is taken out of the religion class. She loves comic books, but is informed that Mickey Mouse is a fascist. She doesn’t like opening her bedroom door and seeing strangers at all hours of the day and night. She is very displeased, and young Kervel, who was around 9 when the film was made, gives an astonishing performance and shows that in some ways the character is more mature than her parents.

She has an instinctive logic that won’t accept all their instructions. Lectured on “group solidarity,” she decides to practice it one day in school. When the nun asks a question and Anna knows the answer, she nevertheless raises her hand along with all the other students, who are wrong. She knows they are wrong, I think, and this is her way of pointing out a flaw in the solidarity theory. Another day she is more specific, asking innocently how group solidarity differs from the behavior of sheep.

In the scenes in which Anna figures, the film is shot almost exclusively from her eye-level. This is particularly effective when her parents take her along on a political demonstration, and what she sees are blue jeans, running shoes and tear gas. It is foolhardy to take a kid to a potentially violent demonstration and foolish of her parents to think she must be instantly radicalized. But they do love her, and so do her grandparents, and so do the nannies who seem to come and go. (One of them, a Cuban refugee, confides in Anna that communists are barbarians.)

The movie involves the adult children of two famous filmmakers. Its director, Julie Gavras, is the daughter of the Greek director Costa-Gavras, who made “A State of Siege” and other pro-revolutionary films. Interesting to speculate that the screenplay, although based on an Italian novel by Domitilla Calamai, may in some respects reflect the director’s own girlhood. And Marie, Anna’s mother, is played by Julie Depardieu, daughter of Gerard. Was Julie’s father also mercurial, zealous and changeable, but loving? And were the childhood homes of both women filled with wine-drinking strangers night after night?

It is a blessing that “Blame It on Fidel” doesn’t pull back to answer such questions, but focuses resolutely on the world as seen through 9-year-old eyes. Kids don’t care if millions are starving in South America nearly as much as they care that three-course family meals have been replaced by weird-looking casseroles. They don’t care if there really is a God nearly as much as they like the nun who teaches divinity class. They’re not thrilled that their parents are away in Spain or Chile fighting evil; they want them at home every night. And no matter what Anna is told, she knows these things are true, and will not be swayed.

The film contains a surprising amount of understated humor. It is not a grim portrayal of a harsh upbringing, but an affectionate portrait of parents who will be able to change the world before they will be able to change their daughter. Anna and her parents continue to love one another above all, and so this is not an angry film but a wry, observant one. It could have been worse for Anna; consider Sidney Lumet’s “Running on Empty” (1988), about the family of radical underground members in hiding. Anna’s parents haven’t bombed anyone, although they do circulate lot of petitions.