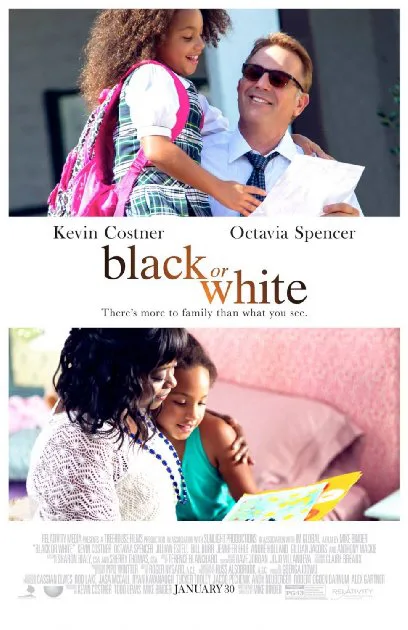

“Black or White,” a domestic drama about a custody battle over a mixed-race child, is the kind of movie you root for, because it’s clearly coming from a sincere and honest place. But it’s often painful, and not in a good way; it’s painful because of the roads it doesn’t explore, the shortcuts it takes, and the special pleading it can’t stop itself from indulging in.

Written and directed by Mike Binder, and bankrolled by star Kevin Costner, it wants to illuminate and heal through straight talk, and if you look at it purely as a commercial venture, there’s no denying its specialness. There are no superheroes, no robots, no dinosaurs, no guns, nothing that producers would consider exploitable elements. There’s no easy marketplace slot into which it can be placed and nurtured. It’s what used to be called, in the 1950s and ’60s, a “problem picture.” In this case the problem is racial distrust, and how it’s perpetuated in a country that likes to think of itself as post-racial, and that’s filled with people who think they’re not racist, not at all, no sir, no ma’am.

Unfortunately, “Black or White” is itself part of another sort of problem: the tendency to center what ought to be an extended family’s drama on the distress of a White man—in this case, Costner’s character, Elliott Anderson, a recently widowed and visible wealthy grandfather. Elliott wishes people would recognize how hard he’s trying and how good his heart is, and just leave him alone in his big house with its big swimming pool and his Mexican maid to raise his young granddaughter Eloise (Jillian Estell). The poor girl’s White mother died in childbirth, and barely knew her African-American father, Reggie (Andre Holland of the excellent Cinemax series “The Knick”), a drug addict who got Eloise’s mother pregnant and has barely been heard from since.

The film starts strong in a hospital waiting room, dropping you right into the worst moment of Elliott’s life: learning that his wife (Jennifer Ehle) died of injuries sustained in a car wreck. The film’s sincerity is instantly apparent, along with its sense of empathy. The movie has a lot of problems, which we’ll deal with momentarily, but for a while, at least, deck-stacking isn’t one of them. Elliott is no plaster saint. He’s a Baby boomer who probably considered himself race-blind until his daughter started sleeping with Reggie and ended up bearing his child. But he means well, and his actions prove it. He quickly assumes child-raising duties once performed by his wife, including combing Eloise’s hair and tying it with a bow (his form is lacking, to put it mildly), and even hires a tutor, Duvan Araga (Mpho Koaho of TNT’s “Falling Skies”), to help the girl with math homework that he can’t make heads or tails of.

Then Eloise’s grandmother Rowena Jeffers (Octavia Spencer) enters the picture and agitates for custody of Eloise. She’s a pillar of the community who lives in a modest but comfortable house in South Central L.A. and owns two other homes and six businesses. He motivations in the custody fight, like Elliott’s, are complex and conflicted: self-serving in some ways, quite reasonable in others. She wants Eloise to explore the other side of her heritage by spending time with her African-American relatives. She wants the girl to grow up surrounded by loved ones who can support her during a period of grieving, rather than living in near-isolation in a big, bland house with grandpa and his maid. And she wants to keep Eloise safe by giving her a haven from Elliott’s drinking, which has grown so severe in the aftermath of his wife’s death that he pays Duvan to drive Eloise to school while he sits in the passenger seat, muttering and reeking of booze.

Binder, who oversaw one of Costner’s best performances in “The Upside of Anger,” based this story on what happened to his nephew, a biracial child whose dad was out of the picture and whose mom died at 33. There are scenes in which seeming voices of reason say and do petty, self-destructive or outright stupid things, and scenes in which irritating or fundamentally untrustworthy characters blurt out something that’s undeniably true. The performances range from solid to excellent. First among equals is Costner, who’s fearless about letting Elliott be hurtful, maudlin and pathetic at times. Spencer puts across Rowena’s common sense and bulldozer righteousness as well as an impulsive, self-defeating busybody quality that alarms her own adult kids; their ranks include her son Jeremiah (Anthony Mackie), a lawyer who warns Rowena that the only way to win custody is to paint Elliott as a racist, a charge that’s probably true in certain ways but that will need to be puffed up to monstrous dimensions in court.

But too often the actors seem to struggle with dialogue and situations that turn their characters into clownish adversaries and stick-figure obstacles. Mackie’s lawyer is one casualty: he’s there mainly to inflame tensions and push Rowena to green-light extreme and ultimately counterproductive tactics. Another is Holland, who deserves a medal for making an increasingly repellent and nonsensical character watchable. To its credit, “Black or White” keeps insisting that we sympathize with Reggie’s struggle to stay clean, and understand that he’s been placed in an impossible position: Rowena’s side of the family has a better shot at custody if he can prove he’s cut out to be a father, but you need only look into his haunted, guilty eyes to see that he’s not.

Unfortunately, Reggie ends up validating White stereotypes of absentee Black fathers who would rather smoke crack than raise their kids; he’s a hapless version of the sort of bogeyman that might have made its way into a 1980s State of the Union address about the failures of liberalism. The movie never subverts the stereotype, even in its more laudable moments, such as a nifty bit of crosscutting that reminds us that Reggie’s drug habit and Elliott’s drinking are both about numbing unbearable pain.

In the end, “Black or White” is too disorganized and pokey, and too comfortable with sitcom-like clowning, to truly illuminate or heal. Too many scenes verge on sitcom broadness, and even the more delightfully original supporting players (including Duvan, who speaks several languages fluently and has written thesis papers on every conceivable subject) wear out their welcomes. Worse still is the way that “Black or White” keeps the focus on Elliott rather than distributing its screen time more democratically, a strategy that might have countered complaints that the film is mainly concerned with proving that Elliott is not a racist, and that by extension, White viewers who identify with Elliott aren’t racists, either.

The movie uses the n-word in a couple of pivotal scenes, and not casually either, but it’s impossible to congratulate the film for daring to go there when Elliott gets the chance to explain himself and launches into what sounds like the sort of half-apology, half-excuse that a White movie star might make after being caught using bigoted language in public. His assertion that most people have racist thoughts from time to time, but what matters isn’t our first thought but our second and third, rings true. But putting it in the mouth of a rich White man is still a baffling strategic mistake—though not nearly as ill-advised as establishing Reggie’s weak claim on custody by revealing that he doesn’t know how to spell his daughter’s name. And the melodramatic climax, which momentarily endorses Elliott’s ugliest fears, is such a tawdry betrayal of the movie’s nobler impulses that “Black or White” never recovers from it.

This movie is the kind of failure that makes you frustrated and sad rather than angry. Its heart is in the right place, but its mind is confused.