“Bicentennial Man” begins with promise, proceeds in fits and starts, and finally sinks into a cornball drone of greeting-card sentiment.

Robin Williams spends the first half of the film encased in a metallic robot suit, and when he emerges, the script turns robotic instead. What a letdown.

Williams plays a robobutler named Andrew, who arrives in a packing crate one day outside the home of a family who is destined to share him for four generations, each and every moment of which seems mercilessly chronicled. His first owner is Sir (Sam Neill), who introduces Andrew to a dubious wife (Wendy Crewson) and a daughter named Little Miss, who grows up to be played by Embeth Davidtz (she also plays her own granddaughter).

At first the robot is treated unkindly. “It is a household appliance, yet you treat it like it is a man,” an associate frets to Sir. It’s clear from the first that Andrew is some kind of variant, smarter and more “human” than your average robot, although just as literal.

In the early scenes, which have a life of their own, Andrew jumps out a window when told and has a lot of trouble mastering the principle of the “knock-knock” joke. He also demonstrates various consequences of the Three Laws of Robotics, which were obviously devised by Isaac Asimov so that men of the future will be able to shout “gotcha!” at their robots.

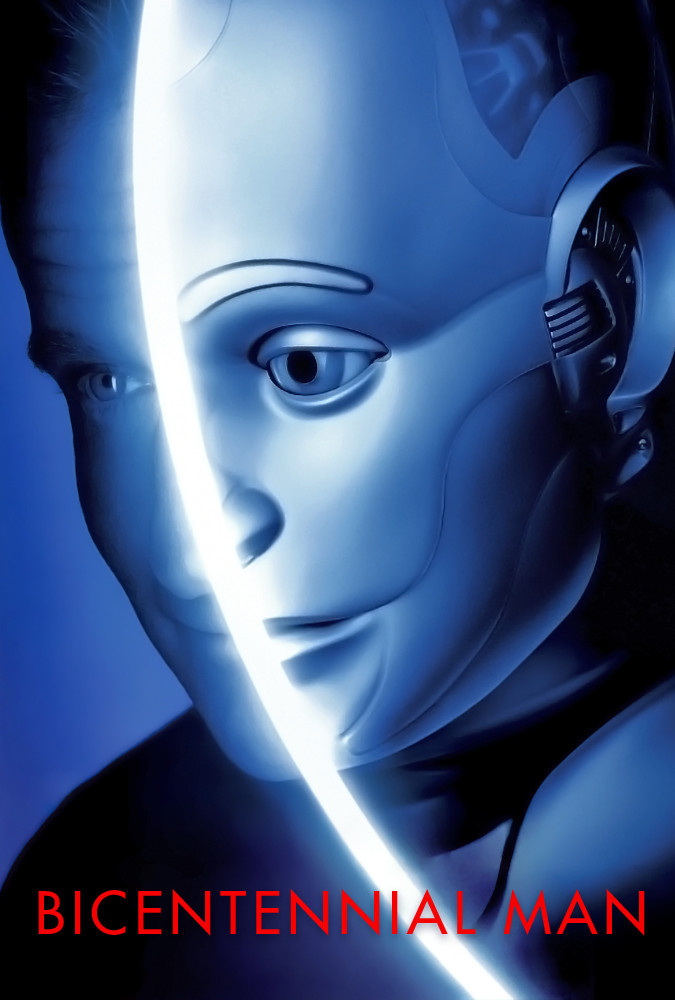

From the first moment we see Andrew, we’re asking ourselves, is that really Robin Williams inside the polished aluminum shell? USA Today claims it is, although at times we may be looking at a model or a computer-generated graphic. The robot’s body language is persuasive; it has that same subtle courtliness that Williams himself often uses. Andrew also has good timing, which is crucial, since many of the movie’s payoffs depend on the robot expressing its feelings through body language. (“One would like to have more expression,” Andrew complains at one point. “One has thoughts and feelings that presently do not show.”) Peter Weller, who starred in “RoboCop,” told me it was the most excruciating physical ordeal of his lifetime, spending weeks inside a heavy costume under movie lights that raised the temperature to more than 100 degrees. Williams must have undergone a similar ordeal. His performance depends on the comic principle that it’s funny when a man is subjected to the rules of a machine; everything we see here has its mirror image in the assembly-line sequence at the beginning of Chaplin’s “Modern Times.” Unfortunately for this movie, it’s funnier when a man becomes a machine than when a machine becomes a man, because man’s free will is being subverted, while the machine has none.

The plot is based on a story by Asimov and a novel by Asimov and Robert Silverberg. It deals with the poignancy of an android that has humanlike feelings and must live indefinitely, while all the humans must die. There are consolations. Andrew is allowed to bank his own income and compound interest can work wonders for an immortal being; eventually he is rich, and goes on an odyssey to find a soul mate.

His search leads to the shabby laboratory of Rupert Burns (Oliver Platt), who tinkers with used robots, and the two of them fashion a new body for Andrew that looks much like Robin Williams. There is also the problem of finding Andrew a soul mate. Will it be an advanced robot, or will his own progress make it plausible for him to consider a relationship with a human? Andrew can’t reproduce, of course, but logic suggests he might make a versatile and tireless lover.

The movie’s buried themes have to do with self-determination and the rights of the individual. Like many of Asimov’s robot stories, it deals with the enigma of having the intelligence of a man, without the rights or the feelings. “Bicentennial Man” could have been an intelligent, challenging science fiction movie, but it’s too timid, too eager to please. It wants us to like Andrew, but it is difficult at a human deathbed to identify with the aluminum mourner.

Strange, how definitely the film goes wrong. At the 60-minute mark, I was really enjoying it. Then it slowly abandons its most promising themes and paradoxes, and turned into a series of slow, soppy scenes involving love and death. And since the beloved woman is essentially always the same person (played by Davidtz) the movie begins to seem very long and very slow, and by the end, when Andrew hopefully says, “See you soon,” we hope he is destined for Home Appliance Heaven.