“Benny and Joon” is a film that approaches its subjects so gingerly it almost seems afraid to touch them. The story wants to be about love, but is also about madness, and somehow it weaves the two together with a charm that would probably not be quite so easy in real life.

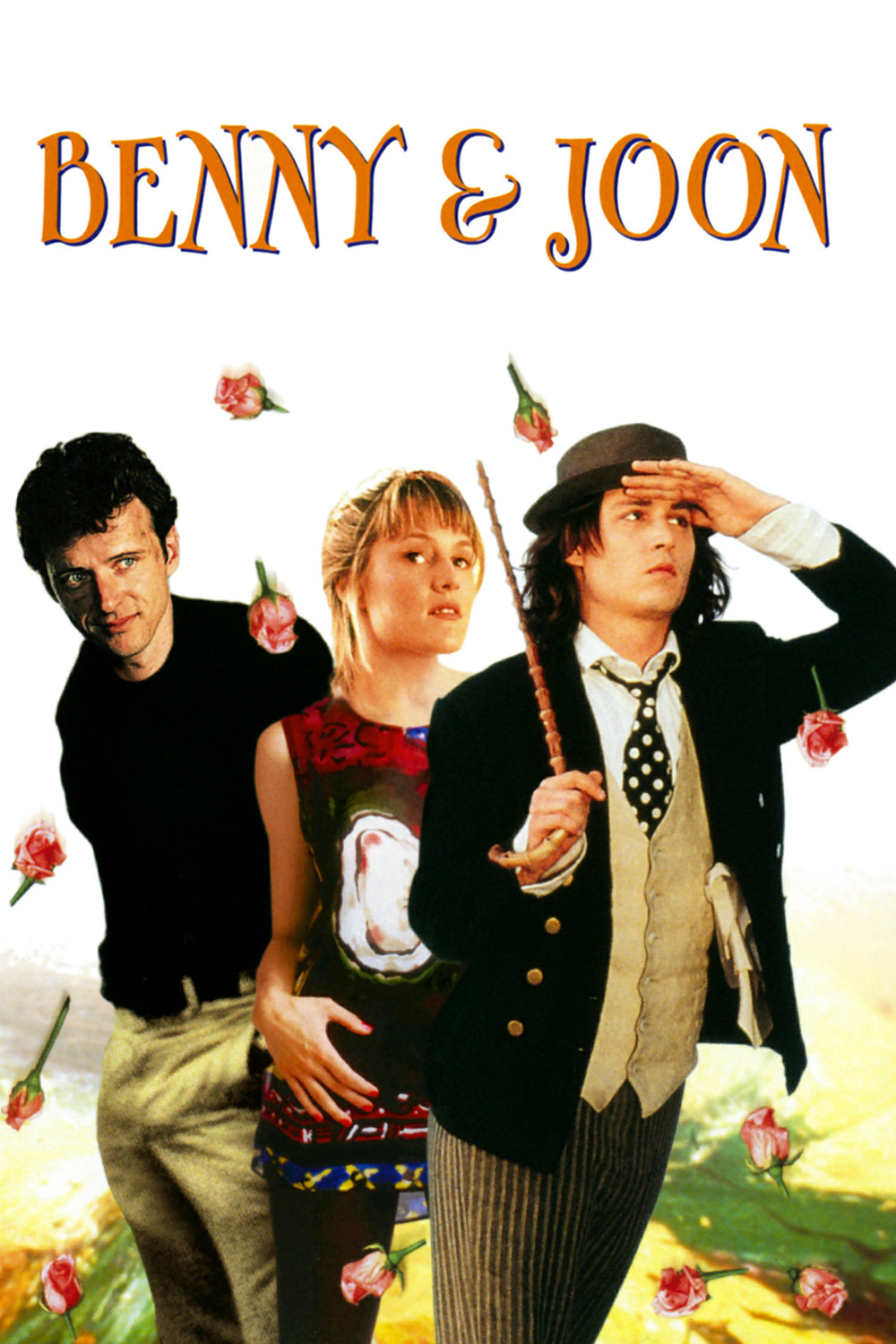

The title characters are two young adults, Benny (Aidan Quinn) and his kid sister, known as Joon (Mary Stuart Masterson). He works to support them. She stays at home and paints, during her good periods, and rages at him, during her bad times. She is schizophrenic, although the screenplay doesn’t ever say the word out loud. When she takes her medication and stays calm and things go smoothly, their lives are blessedly uneventful.

One of Benny’s few pleasures is a monumental, long-running poker game, at which the stakes are all sorts of things other than money.

One night Joon loses a big bet, and is forced to provide temporary room and board for a strange, goofy relative of one of the other players. This is Sam (Johnny Depp), who is sane but lives in a strange blissful moonscape all his own.

The first time we see Sam, riding on the bus, he’s reading a book about the silent clown Buster Keaton. This is not idle curiosity. Sam has somehow determined to internalize the genius of Keaton, Chaplin and the other early screen comedians, and although he never says that out loud, either, it becomes clear in a gradual, unforced way, as he incorporates bits from their films into his daily life.

If I had been reading the screenplay of “Benny and Joon,” I would have started to form ominous misgivings at about this point, since the conceit of bringing a character like Sam into the story seems a little too precious. But Depp pulls it off. In “Edward Scissorhands” he demonstrated two of the skills that are crucial to his performance in “Benny and Joon”: He was able to build an essentially wordless performance out of expression and gesture, and he had natural physical grace.

Here, without ever explaining himself, he simply behaves sometimes in the real world in the way Keaton and Chaplin behaved in their movie worlds.

There is a moment at a lunch counter, for example, when he sticks two forks into two dinner rolls, holds them under his chin, and moves them to suggest that the rolls are his feet, and he is dancing. It’s a steal from “The Gold Rush,” but done with an offhand charm that makes it work all over again.

Sam charms Joon out of her self-absorption, and before long, inevitably, they fall in love. But this is not a romance made in heaven, because neither Sam nor Joon is fitted with all the tools useful for surviving in the modern world.

Benny is enraged at the news that they love each other, because he believes Joon cannot live independently – and also because, having devoted his life to caring for her, he feels a certain possessiveness. A psychiatrist (C. C. H. Pounder, from “Bagdad Cafe“) also has serious reservations.

Because “Benny and Joon” is the kind of movie it is, the problems of reality, while occasionally present, are not entirely given their due. Sam exists so resolutely in his own world that it is even a little startling when, at one point, he quietly asks, “How sick is she?” We can glimpse for a second, under his clown facade, his own take on reality. Then his charming persona slides back into place.

Most people would side with Benny in his opposition to the talk of marriage, but the movie suggests that love and magic can overcome madness, and for at least the length of the film I was prepared to accept that. Much of the credit for that goes to Depp, who takes a character that might have seemed unplayable on paper, and makes him into the kind of enchanter who might be able to heal Joon. Mary Stuart Masterson, from “Fried Green Tomatoes” usually plays commonsensical, sane characters; this time she shows Joon able to swing in an instant from calm to rage, picking on little things that set her off. It’s a convincing performance.

And Aidan Quinn, in a somewhat thankless role as the movie’s reality base and opponent of love, never plays a scene simply for its obvious point, but lets us see that his love for his sister underlies all of his decisions.

“Benny and Joon” is a tough sell. Younger moviegoers these days seem to shy away from complexities, which is why the movie and its advertising all shy away from any implication of mental illness. The film is being sold as an offbeat romance between a couple of lovable kooks. I was relieved to discover it was about so much more than that.